Vasculitides and Connective Tissue Disorders

Andrzej Szuba

Izabela Gosk-Bierska

Richard L. Hallett

Vasculitides

The clinical and pathological features of vasculitis are variable and depend on the site and type of blood vessels that are affected. Diseases in which vasculitis is a primary process are called primary systemic vasculitides. Different classifications will be described, but the final description will be based on the Chapel Hill 1994 Consensus Conference classification. Vasculitis may also occur as a secondary feature in other diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis (1,2).

Systemic vasculitides form a heterogeneous group of vascular inflammatory diseases that can be subgrouped

based on the underlying histopathology and the size of the vessels involved as well as the target organs involved. The resultant clinical picture is illustrated in Table 10-1 (3).

based on the underlying histopathology and the size of the vessels involved as well as the target organs involved. The resultant clinical picture is illustrated in Table 10-1 (3).

Table 10.1 Classification of Vasculitides, Chapel Hill Consensus Conference, 1994 | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Large Vessels Vasculitis

Takayasu Arteritis

Takayasu arteritis (TA), also known as pulseless disease, occlusive thromboaortopathy, and Martorell syndrome is a chronic inflammatory arteritis affecting large vessels (4). It is typically characterized by granulomatous inflammation of the aorta and its major branches, usually occurring in patients younger than 50 years of age. Vessel inflammation leads to wall thickening, fibrosis, stenosis, thrombus formation, and visceral ischemia. Acute inflammation can destroy the arterial media and can lead to aneurysm formation (5).

TA is most commonly seen in Japan, Southeast Asia, India, and South America. In a Japanese population autopsy study, evidences of TA were found in 0.033% of all individuals. Female-to-male ratio was 4.5:1 (6). A study of North American patients by Hall et al. found the incidence to be 2.6 per million per year (7).

Pathogenesis of TA is unknown. Infectious factors including viruses and Mycobacterium are proposed to play a role (5,8,9).

Clinical Manifestation

Manifestations range from asymptomatic disease to catastrophic vascular and neurological complications. TA is usually diagnosed in the second or third decade of life; however, it can occur even in young children. In a large published cohort (n = 107), 80% of patients were between 11 and 30 years, 77% had disease onset between the ages of 10 and 20 years, with time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis of 2 to 11 years in 78% (8). The clinical features of TA in young patients appear to be similar to those of adults (10).

Diagnostic criteria for TA developed by American College of Radiology (ACR) require that at least three of the six criteria are met (11):

Development of symptoms or findings related to TA at age <40 years.

Claudication of extremity: development and worsening of fatigue and discomfort in muscles of one or more extremity while in use, especially the upper extremities.

Decreased pulsation of one or both brachial arteries.

Difference of >10 mmHg in systolic blood pressure between arms.

Bruit audible on auscultation over one or both subclavian arteries or abdominal aorta.

Arteriographic narrowing or occlusion of the entire aorta, its primary branches, or large arteries in the proximal upper or lower extremities not caused by arteriosclerosis, fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), or similar causes; changes usually focal or segmental.

It should be remembered that sensitivity and specificity of ACR (as well as other) criteria to detect TA and other vasculitides varies (71.0% to 95.3% for sensitivity and 78.7% to 99.7% for specificity) in published studies (12,13) and should be used with caution when applied to an individual patient.

Characteristic clinical features of TA (present in over 80% of patients) include:

Diminished or absent pulse, limb claudication, and/or blood pressure discrepancies

Vascular bruits, particularly in carotid, subclavian, and abdominal vessels

Symptoms occurring less frequently are hypertension, aortic root dilatation with aortic regurgitation, chronic heart failure, neurological symptoms (dizziness, visual disturbances, cerebrovascular accident), pulmonary artery involvement, abdominal angina, and myocardial ischemia. Carotidynia and erythema nodosum may occur. Systemic symptoms associated with TA include fever, dyspnea, night sweats, weight loss, arthralgias, and myalgia (7,8,14,15,16,17,18,19).

It should be noted that significant differences in clinical patterns of TA exist between different populations. Aortic root involvement with aortic regurgitation is the most common presentation of TA in the Japanese population, while involvement of abdominal aorta and renal arteries is most frequently found in Indian patients (17).

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

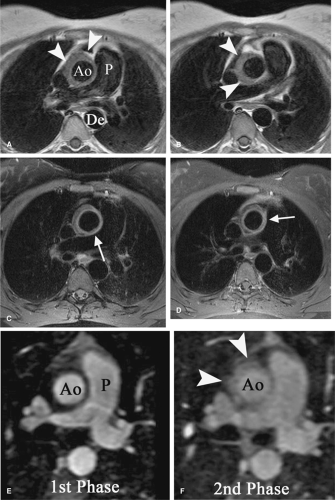

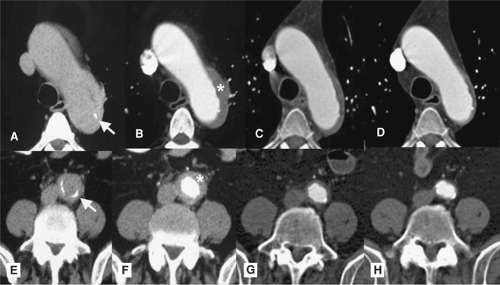

Various sets of criteria may assist in diagnosis of TA. Adequate vascular imaging studies are necessary for assessment of vascular anatomy. Conventional angiography of the aorta and other large arteries has been the gold standard in diagnosis of TA. However, it is being rapidly replaced by computed tomographic (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) angiography, techniques that are less invasive and allow detailed visualization of arterial anatomy in conjunction with characterization of the arterial wall (20) (Table 10-2) (Figs. 10-1, 10-2 and 10-3). Assessment of arterial wall thickness and inflammatory process can help with diagnosis, monitoring of disease activity, and response to therapy (21,22). The

latter, however, needs to be further assessed. As the disease progresses, arterial wall inflammation is replaced by arterial strictures and occlusions (Fig. 10-4).

latter, however, needs to be further assessed. As the disease progresses, arterial wall inflammation is replaced by arterial strictures and occlusions (Fig. 10-4).

Doppler ultrasound is a useful noninvasive procedure for the assessment of vascular anatomy and vessel wall inflammation. Histopathological changes are characteristic for TA; however, the specimens are obtained usually during surgery.

Table 10.2 Angiographic Classification of Takayasu Arteritis, Takayasu Conference 1994 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

Laboratory Evaluation

No biochemical marker specific to TA exists; neither is there a good surrogate marker of disease activity. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were proposed but proved to correlate poorly with disease activity

(23,24,25). More recently, IL-6 and RANTES (26) and plasma matrix metalloproteinases (27) have been proposed as surrogate markers for TA activity.

(23,24,25). More recently, IL-6 and RANTES (26) and plasma matrix metalloproteinases (27) have been proposed as surrogate markers for TA activity.

Histopathology

In the acute phase: vasoritis in adventitia, infiltration by lymphocytes and giant cells with neovascularization in the media, smooth muscle cells, mucopolysaccharides, fibroblasts, and thickening of the intima. In the chronic phase: fibrosis with destruction of elastic tissue is seen.

The differential diagnoses include inflammatory aortitis (syphilis, tuberculosis, Cogan’s syndrome [CS], rheumatoid arthritis, giant cell arteritis [GCA], Behçet disease [BD], Kawasaki disease [KD]), coarctation of the aorta,

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome (MFS), FMD, and neurofibromatosis.

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome (MFS), FMD, and neurofibromatosis.

Treatment

Some patients (about 20%) do not require therapy because of a mild, self-limiting course of the disease. Active disease should be treated with steroids (prednisone 1 mg/kg/d), and in 50% of patients it will result in remission. Cyclophosphamid and/or methotrexate should be added if steroids alone do not control disease. This may result in remission in an additional 40% of steroid-resistant patients (24). Hypertension is frequently observed in TA patients. Treatment of hypertension is critical to prevent cardiovascular complications. However, the diagnosis of hypertension in TA may be delayed in patients with subclavian artery stenosis (24). Surgery or angioplasty may be required for treatment of stenoses once active inflammation has been controlled (28).

Giant Cell Arteritis (Temporal Arteritis)

GCA (temporal arteritis, Horton’s disease, Horton’s giant cell arteritis, giant cell arteritis of elderly) is a granulomatous arteritis of large vessels frequently affecting the temporal artery.

Etiology of GCA is unknown; association with HLA-DR4 and HLA-DRB1 has been reported (29,30). GCA is the most common type of primary systemic vasculitis with an incidence of 200 per million population per year. It usually occurs in patients older than 50 years and is prevalent in women. Sixty-five percent of GCA patients are women >70 years old. Caucasian patients seem to be affected more frequently than Asian and Hispanic patients (31,32,33).

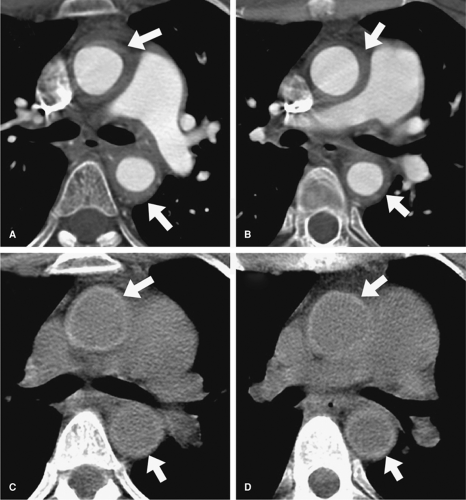

GCA is a granulomatous arteritis of the aorta (Fig. 10-5) and its major branches, especially extracranial branches of the carotid artery. Extracranial artery involvement is present in 15% of GCA patients (34). In a review of 75 patients with extracranial GCA, 25% had asymptomatic temporal arteritis. GCA of the ascending aorta and arch occurred in 39%, the subclavian and axillary artery in 26%, and the femoropopliteal artery in 18% of those patients (34). The risk of development of a thoracic aortic aneurysm is 17 times higher in GCA patients (35). Some authors suggest, however, that GCA of the cranial arteries (classic temporal arteritis) and GCA affecting the subclavian/axillary/brachial arteries are two separate pathological entities (36). Rarely, GCA may present as a breast, ovarian, or other type of tumor (37).

Persistent headache (often unilateral) associated with fever, myalgias, weight loss

Temporal artery changes: swollen and tender to palpation, pulseless

Ischemic manifestations: necrosis of the tongue, multiple cranial nerve palsies, dysphagia, hearing loss, and ischemic stroke

Visual manifestations: partial or complete visual loss may be sudden and painless, diplopia may also occur

Jaw claudication

Frequent association with polymyalgia rheumatica (40% to 62%)

Diagnosis is made on characteristic clinical presentation and markedly elevated ESR (>50, frequently >100). In doubtful cases, biopsy of the temporal artery is the gold standard to confirm the diagnosis of GCA. Arterial biopsy reveals granulomatous inflammatory reaction with destruction and calcification of internal elastic lamina, cellular infiltrates of lymphocytes, macrophages, and giant cells. Areas of fibrosis and neovascularization might be also present (41). Temporal artery biopsy is frequently negative in GCA involving the subclavian/axillary/brachial artery (36). Vascular imaging studies (CT, MR, or catheter angiography) should be performed in patients with visual disturbance, limb claudication, suspected involvement of aorta, or other large arteries (42).

Treatment with corticosteroids (prednisone 60 mg to 80 mg/d) should be started as soon as the diagnosis is suspected to avoid visual loss (43). After 6 weeks, the prednisone dose may be slowly tapered to a minimal maintenance dose of 5 to 10 mg/d. Mean duration of therapy is 1 to 2 years; however, some patients require 4 to 6 years of treatment (24). GCA arterial aneurysms may require surgery (44).

Cogan’s Syndrome

CS (45) is a rare disorder of children and young people of unknown etiology. Autoimmune mechanisms are suspected. It is characterized by inflammatory eye disease (interstitial keratitis, uveitis, scleritis, optic neuritis) and audiovestibular symptoms resembling Meniere’s attacks. CS is associated with vasculitis and aortitis. The onset is usually rapid with ocular symptoms followed within a year by tinnitus, vertigo, nausea and vomiting, and hearing loss. The majority of untreated patients will become deaf, and 5% will become blind (46). Systemic manifestations may be present in half of the patients and include fever, musculoskeletal pains, fatigue, and weight loss. Splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy might also be detected. Aortitis with aortic insufficiency develops in 10% to 15% of patients. Aneurysms of the thoracic and abdominal aorta are also reported. Other vessels including the coronary, renal, extremity, and cerebrovascular arteries may be involved (46,47,48,49,50,51).

Laboratory evaluation reveals elevated sedimentation rate, anemia, thrombocytosis, and leukocytosis (48). Histological findings in aortitis show involvement of intima and media with cellular infiltrates of neutrophils, mononuclear cells and giant cells, disruption of the internal elastic lamina, and scarring (52). Diagnosis can be suspected in patients with interstitial keratitis and audiovestibular symptoms after infectious etiology (syphilis) is ruled out.

Isolated Vasculitis of the Central Nervous System

Isolated vasculitis of the central nervous system (IVCNS) or primary angiitis of the CNS is a vascular inflammatory disease of the CNS involving mainly small and medium-sized leptomeningeal and parenchymal arteries. It is a rare disease that may present with a variety of neurological symptoms. Headache, focal neurological deficits, stroke, seizures, memory loss, personality changes, and loss of consciousness may appear. Patterns of progressive encephalopathy, space occupying lesions, or multiple sclerosis-like disease have been described (54).

Diagnosis is usually suspected after cerebrovascular angiography. Multifocal segmental or diffuse narrowing of arteries is seen; arterial dilatation and aneurysms are less common (55). Angiographic presentation is not specific for IVCNS and occasionally may be normal (56). MR and CT angiography can be helpful in visualization of vascular and parenchymal CNS changes (57,58).

Brain biopsy is usually necessary to confirm diagnosis of IVCNS (55,59). The histological picture is heterogeneous and may reveal granulomatous, necrotizing, or lymphocytic vasculitis often coexisting in the same patient. Vascular thrombosis may be present (55).

Aggressive immunosuppressive treatment with systemic steroids and cytotoxic agents improved the outcome of IVCNS (59).

Medium Vessels Vasculitis

Inflammation affecting predominantly visceral arteries is classified as medium vessels vasculitis. This group includes two vasculitis syndromes: polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) and Kawasaki disease (KD).

Polyarteritis Nodosa

PAN (classic polyarteritis nodosa, periarteritis nodosa) is a rare systemic necrotizing vasculitis of medium and small arteries frequently associated with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (7% to 30% of patients have HBs antigen) (60). The majority of affected people are in the fourth to fifth decade of life; men are more frequently affected than women (M:F ratio is 2–3:1). Arterial inflammation leads to formation of aneurysms and thrombosis of affected arteries with ischemia or infarction of supplied organs and/or rupture of an aneurysm.

Etiology of PAN is unknown. Association with HBV infection can be documented only in a minority of patients (7%) (60); however, the rate of latent HBV infection may be higher (61). Other viruses (cytomegalovirus, parvovirus B-19, human T-cell lymphotropic virus [HTLV-1], and hepatitis C virus [HCV]) are also occasionally implicated in PAN etiology (62,63,64).

Pathology

Arterial lesions affect segments of medium-sized arteries and frequently are localized at the branching points. Necrosis and inflammatory infiltrates of mononuclear cells are found in the adventitia and media with disruption of the internal elastic lamina. Weakened arterial walls lead to the formation of aneurysms. Intimal proliferation and arterial thrombosis may occur.

Laboratory Finding

Clinical Presentation

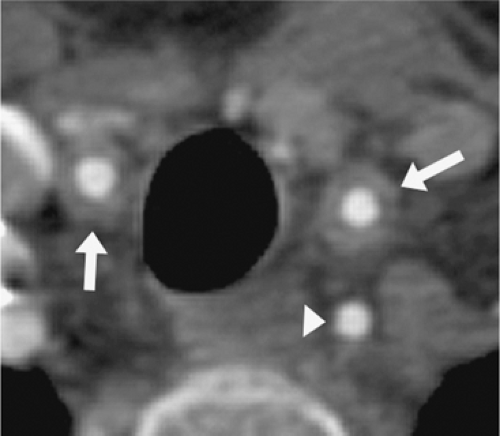

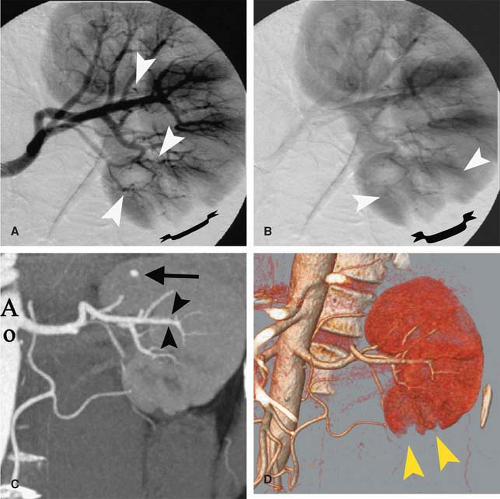

Constitutional symptoms include weakness, myalgias, arthralgias, fever, and weight loss frequently >4 kg. Symptomatology of PAN depends on presence and severity of organ involvement. Kidneys, gastrointestinal system, muscles, and the central and peripheral nervous system are often affected. Involvement of lungs is rare. Kidneys are affected in up to 60% of patients (Fig. 10-6) (cortical infarcts, renal vasculitis, rupture of renal artery aneurysm) (66,67)—glomerulonephritis is absent in PAN by definition. Neurological symptoms related to CNS disease are present in 10% to 25% of PAN patients (68). Cerebral artery occlusion may result in stroke, seizures, amaurosis, and cognitive impairment. Peripheral neurological involvement is present in up to 50% of patients and include polineuropathy, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and mononeuritis multiplex (24,69,70).

Gastrointestinal symptoms are present in more than half of patients. Symptoms are related to bowel ischemia (abdominal angina, ischemic colitis, acute abdomen due to intestinal necrosis and/or perforation) (71,72); occasionally, acute pancreatitis, appendicitis, or cholecystitis may develop (24,72,73).

Cardiovascular involvement is common and includes arterial aneurysms and stenoses/occlusions in peripheral arteries (74), including renal (67), cerebral (75), mesenteric (76), and coronary arteries (77,78). Congestive heart failure may develop. Involvement of the limb arteries is also frequent (74).

Musculoskeletal manifestations of PAN include polymyositis (in up to 40%) (79), arthralgia, and occasionally polyarthritis (24).

Skin lesions are less frequent and include subcutaneous palpable purpura, painful inflammatory nodules, and livedo reticularis. Orchitis with testicular pain and tenderness may be found in 10% to 15% of male patients (24).

Diagnosis of PAN may be difficult because of the variety of clinical presentations and infrequent occurrence. It should be suspected in any case of unexplained systemic diseases with multiorgan involvement.

Biopsy of affected tissue can confirm the diagnosis. Biopsy of affected skin or muscles can document presence of necrotizing vasculitis. Sural nerve biopsy may reveal necrotizing vasculitis of epineural arteries in the presence of conduction abnormalities, even in the absence of clinical symptoms of neuropathy (24,80,81).

Angiography can help in the diagnosis of PAN. Evidence of multiple microaneurysms and arterial ectasia, especially in visceral arteries, is thought to be specific for PAN and is found in 40% to 75% of patients (67,74,82). The majority of PAN patients have evidence of arterial occlusions in visceral vessels (74).

Treatment

PAN therapy should be tailored to the severity of presentation. In milder cases (without renal, CNS or cardiac involvement), only steroids (prednisone 1 mg/kg/d) are recommended. Cyclophosphamide 500 to 1,000 mg intravenously (IV) once every 2 weeks (six rounds) should be added in more severe cases. The duration of therapy should last 12 months (83).

Treatment of PAN associated with HBV additionally requires an antiviral drug such as interferon or/and lamivudine in combination with plasmapheresis (84). Aggressive immunosuppression should be limited to life-threatening complications (85,86). Low-dose aspirin is recommended for thrombocytosis. Surgical intervention is necessary in acute abdominal catastrophies (e.g., bowel perforation or hemorrhage).

Prognosis depends on severity of presentation. Five-year mortality varies from 12% to 46%, depending on initial presentation and organ involvement (83).

Kawasaki Disease

KD (mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome) is an acute febrile illness of childhood first described by Kawasaki in 1967. KD affects children usually under the age of 12 years with the peak incidence in children 18 to 24 months old. In Japan, the incidence exceeds 100 to 150/100,000 children <5 years but is 4 to 15/100,000 in this age group in the United States (87).

Diagnosis

KD is an arteritis affecting large, medium, and small arteries and is associated with mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome. It is probably the most common vasculitis in children. Diagnosis is based on clinical criteria: at least 5 days of fever and four or five signs of mucocutaneous inflammation rather than angiographic findings or biopsy. Features of mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome include:

Fever for >5 days

Bilateral nonpurulent conjunctivitis

Polymorphous exanthem, macular polymorphous rash on trunk

Characteristic oral mucosal changes of lips and oral cavity: dry, red, fissured lips, “strawberry tongue”

Acute nonsuppurative cervical lymphadenopathy

Typical extremity changes: red palms and soles, indurative edema, desquamation of fingertips during convalescence

Other symptoms: abdominal pain, aseptic meningitis, encephalopathy

The most serious feature of KD is coronary arteritis, leading to coronary artery aneurysms and/or occlusions in 25% of untreated patients. Cardiac involvement is usually asymptomatic; however, it may lead to coronary incidents including sudden death in children and young adults. In a review of 74 cases, mean age of presentation of KD cardiac sequelae was 24.7 ±8.4 years. The most common presentation was chest pain (60%); arrhythmia occurred in 10% of cases. Sudden death was a first presentation in 16% of cases. In a majority of cases, symptoms were triggered by exercise. Two thirds of patients had coronary occlusions on angiography. Coronary aneurysms were found in all autopsy cases (88). Aneurysms and thromboses of peripheral arteries leading to limb gangrene are uncommon (89,90,91,92,93).

Laboratory and Other Diagnostic Methods

Laboratory abnormalities include elevated ESR, CRP, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, proteinuria, and abnormal liver function tests. Early echocardiogram with follow-up study after 4 to 6 weeks is recommended to detect cardiac involvement (94). Electrocardiogram frequently reveals various conduction abnormalities. Evidence of myocardial ischemia and myocardial infarction (MI) may also be present (95,96).

Treatment

Standard therapy with IV immunoglobulin (IVIG; 400 mg/kg/d IV for 4 days) and aspirin (80–100 mg/kg/d by mouth [PO] for 2 weeks) given within the first 10 days of illness greatly reduces this risk of coronary artery aneurysms (CAA). Unfortunately, approximately 5% of children still develop CAA after KD, and a larger number demonstrate coronary artery ectasia (2). Corticosteroid treatment has been controversial since a report by Kato (97) that patients treated with steroids alone had a higher incidence of CAA. A recent study indicated beneficial effects of steroids in patients with severe KD who did not respond to IVIG (98).

Small Vessels Vasculitis Associated with Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody (ANCA+)

Small vessels vasculitis primarily affects vessels other than arteries, especially capillaries and venules. Depending on the anatomic sites of involvement, patients with small vessels vasculitis may present with purpura, glomerulonephritis, or pulmonary capillaritis.

Wegener’s Granulomatosis

Wegener’s granulomatosis (WG) is a necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis affecting small- to medium-sized vessels. The upper and lower respiratory tracts and kidneys are most

frequently involved. Estimated annual incidence in Europe is 5 to 20 per million (99,100,101,102), being highest in Great Britain and Norway. WG affects individuals in their fourth to sixth decade of life, equally among men and women.

frequently involved. Estimated annual incidence in Europe is 5 to 20 per million (99,100,101,102), being highest in Great Britain and Norway. WG affects individuals in their fourth to sixth decade of life, equally among men and women.

Pathology

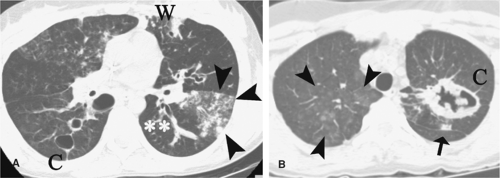

Necrotizing vasculitis of small- and medium-sized arteries and chronic granulomatous inflammation are the two pathological hallmarks of Wegener’s disease. Granulomas contain macrophages, giant cells, epithelioid cells, foci of tissue necrosis, and fibrosis. Granulomas in the lung may coalesce into larger masses that cavitate (Fig. 10-7). The vasculitis affects capillaries particularly in the lung, causing lung hemorrhages. Kidney biopsy frequently demonstrates glomerulonephritis that may be segmental, global, focal, or diffuse with capillary thrombosis. Affected arteries or arterioles show an inflammatory infiltrate and fibrinoid necrosis with destruction of the internal elastic lamina. There is no or little deposition of immune complexes within the kidney or vessel walls (1,24).

Clinical Findings

The classic triad of WG symptoms includes involvement of the upper airways, lungs, and kidneys. Disease may begin acutely with systemic presentation or may be limited to one organ, with years of delay before the next area of the body is affected. The onset of WG may be acute or insidious. The course may be fulminant with multiorgan involvement quickly leading to death or chronic, lasting years before the diagnosis is made (103).

Ninety percent of patients present with symptoms from upper respiratory tracts: perforation of the nasal septum, bleeding, obstruction and collapse of the nasal bridge, tracheal stenosis, and chronic sinusitis, occasionally with otitis media, hearing loss, and vertigo.

Lungs are affected in 70% to 80% of patients. Symptoms of pneumonia, occasionally with massive hemoptysis from alveolar hemorrhage, are frequently present. Kidneys are involved in 48% to 80% of WG patients (proteinuria, hematuria, erythrocyte casts). Arthralgias and arthritis are frequent. Cutaneous lesions include palpable purpura, and skin ulcerations resembling pyoderma gangrenosum are present in half of patients. Other symptoms include ocular involvement (frequent) with conjunctival hemorrhages, scleritis, uveitis, keratitis, proptosis, ocular muscle paralysis, central and peripheral nervous system granulomas with cranial nerve palsies, sensory neuropathy, and mononeuritis multiplex. Cardiovascular involvement is not frequent but includes coronary arteritis that may lead to MI, pericarditis, cardiomyopathy, aortitis, and aneurysm formation (104). Gastrointestinal vasculitis is uncommon but may cause bowel perforation, fatal hemorrhage, and bloody diarrhea. WG may also present as a tumor (e.g., breast tumor) (1,24,105,106). Constitutional symptoms of WG include fever, malaise, fatigue, and weight loss.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation, histopathological assessment, and serological evidence. The ACR criteria include (107):

Abnormal urinary sediment (red cell casts or microhematuria)

Abnormal chest x-ray (nodules, cavities, or fixed infiltrates)

Oral ulcers or nasal discharge

Granulomatous inflammation on biopsy

The presence of two or more of these four criteria is associated with a sensitivity of 88.2% and a specificity of 92.0%.

Biopsy material is usually acquired from lung or upper airways lesions. Serological evidence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) strongly supports the diagnosis. c-ANCA is almost always present in patients with WG. Other laboratory findings include elevated ESR, CRP, leukocytosis, and anemia (24).

Imaging studies are also helpful in assessment of vascular involvement in WG.

Treatment

Previously, untreated WG usually had a fatal course with median survival of 6 months from diagnosis. However, current therapy has greatly improved the prognosis for WG patients. Early diagnosis is crucial. Cyclophosphamid 1–2 mg/kg/d PO (or 800–1,000 mg IV once every 2–4 weeks during 3–6 months) with a low dose of prednisone should be continued for 1 year, then tapered and discontinued after 18 to 24 months. This regimen led to improvement in 91% of WG patients and caused remission of WG in 75% of WG patients (108). In nonresponders methotrexate and prednisone are the alternative therapy, inducing remission in over 70% of patients (109). Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was found to be useful in control of the upper respiratory tract lesions. Currently, etanercept, a TNF-alpha antagonist, is undergoing evaluation for efficacy in WG patients (110). Early results in WG patients are promising (111).

Microscopic Polyangiitis/arteritis

Microscopic polyangiitis/arteritis (MPA) is a small vessel nongranulomatous necrotizing systemic vasculitis with focal segmental glomerulonephritis. Prevalence of MPA is estimated on 1 to 2 cases per 100,000. The onset of MPA is usually around the age of 50; women are less frequently affected. Patients with MPA usually have glomerulonephritis, and rarely, disease may be limited to the kidney. No granuloma formation is seen. Cutaneous, musculoskeletal, neurological, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal involvement is frequent.

Clinical Presentation

Patients usually present with symptoms of systemic disease and quickly deteriorating renal function due to rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Lung involvement is common, and alveolar hemorrhage occurs in 12% to 29% of patients. Otherwise, clinical presentation may resemble PAN. Myalgias, arthralgias, and arthritis are present in 65% to 72% of the patients. Cutaneous vasculitis (palpable purpura, livedo reticularis, digital gangrene) is found in 44% to 58% of the patients. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms of abdominal pain are found in 32% to 58% and GI bleeding in 29%; peripheral neuropathy occurs in 14% to 36% of cases. Cardiovascular system involvement is manifested by hypertension (34%), congestive heart failure (17%), pericarditis (10%), and MI (2%). Ocular manifestations and ear, nose, and throat lesions are commonly seen (112,113).

Laboratory Findings

ANCA are found in 75% to 90% of MPA patients; p-ANCA (perinuclear) are more prevalent than c-ANCA (114,115). ANCA testing is used both for the diagnosis and monitoring disease activity (116). Other laboratory studies usually reveal elevated ESR, leukocytosis, normocytic anemia, elevated creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen (BUN). Urinalysis shows proteinuria, leukocyturia, and hematuria with erythrocyte casts.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually based on clinical presentation, presence of ANCA, and histopathological findings from biopsy. Biopsy can be taken from affected lung, skin lesions, kidney, or sural nerve.

Histologically, vascular lesions are identical to PAN but are present in arterioles, capillaries, and venules (in PAN small- and medium-size arteries are affected).

Imaging studies can help to delineate organ involvement. Visceral angiography usually does not show the microaneurysms, however.

Treatment

Choice of therapy depends on the severity of clinical presentation. Therapy usually begins with oral or IV steroids. Use of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and other cytotoxic agents should be limited to the most severe cases not responding to steroids (117,118). Patients with lung involvement and capillary hemorrhage may require concomitant plasmapheresis (114). Improvement with therapy is seen in 90% of patients, with 75% entering remission. Relapse occurs in 30% of patients (114,119).

Churg-Strauss Syndrome

Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS) (allergic granulomatous angiitis) is a rare systemic granulomatous necrotizing vasculitis originally described by Churg and Strauss in 1951.

Estimated incidence is 2.4 per 100,000 people per year (120). Men are affected more frequently than women; M:F ratio is around 2:1. Peak age of onset is typically in the fourth to fifth decade of life.

Estimated incidence is 2.4 per 100,000 people per year (120). Men are affected more frequently than women; M:F ratio is around 2:1. Peak age of onset is typically in the fourth to fifth decade of life.

CSS is associated with an atopic tendency, usually asthma, and characterized by pulmonary and systemic necrotizing vasculitis, extravascular granulomas, and eosinophilia.

Clinical Presentation

Adult onset asthma usually develops 2 to 3 years before symptoms of vasculitis occur. Patients present commonly with asthma that is frequently severe, and with symptoms of systemic disease.

In a series of 96 patients with CSS, asthma was the most common presentation (97%) followed by mononeuritis multiplex in 77%, sinusitis (61%), and skin lesions (palpable purpura, urtricaria, skin nodules, digital gangrene) in almost half of patients. Pulmonary infiltrates (Loeffler’s syndrome, pneumonia) and/or hemoptysis were found in over one third of patients. Gastrointestinal involvement (GI bleeding, perforation, abdominal pain, pancreatitis) were present in 30% of cases. Kidney involvement was common with focal segmental or crescentic glomerulonephritis, but symptoms were usually mild and rarely progressed to renal failure. Cardiovascular manifestations included coronary vasculitis, MI, pericarditis, myocarditis and congestive heart failure; occasionally, coronary aneurysms and dissections were reported. Cardiovascular complications were the major cause of death in CSS patients. The CNS was infrequently affected; however, cerebral infarct and fatal cerebral hemorrhages were reported (121,122). Hypercoagulopathy with formation of intracardiac thrombus and peripheral thromboembolism has also been reported in CSS patients (123,124). Constitutional symptoms include fever, fatigue, myalgias, and weight loss.

Classic presentation of CSS may be less frequent today thanks to routine use of inhaled steroids in therapy of asthma. Low-dose steroids may modify the presentation of CSS, making the diagnosis more challenging (125).

Laboratory findings include eosinophilia >10% of white blood cells (WBC), anemia, and elevated ESR and CRP. ANCA are detected in half of patients. p-ANCA are prevalent in CSS (121). Other findings include elevated serum immunoglobulin E (IgE), eosinophilic cationic protein, thrombomodulin, and soluble interleukin-2 receptor. Eosinophilia in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid is found in one third of patients.

Diagnosis of CSS is made on the presence of classic clinical symptoms and laboratory/ histopathologic findings. Six criteria were proposed by the ACR for CSS classification: (1) asthma, (2) eosinophilia (>10% of WBC), (3) paranasal sinusitis, (4) transient pulmonary infiltrates, (5) histologic evidence of vasculitis with extravascular eosinophils, and (6) mononeuritis multiplex or polyneuropathy. The presence of four or more findings is associated with a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 99.7% (126).

Biopsy of skin, lung, kidney, or muscles may help the diagnosis. Histologic findings in CSS include the presence of segmental necrotizing vasculitis with eosinophilic perivascular infiltrates and small necrotizing granulomas with central eosinophilic core (usually found in lungs) (122).

Treatment

Corticosteroids (prednisone 0.5–1 mg/kg/d orally) are sufficient therapy in the majority of CSS patients. IV methylprednisolone may be necessary in severe cases. Steroid therapy is continued until symptoms resolve, then slowly tapered. Twelve months of steroid therapy is usually sufficient (117).

In patients who are nonresponsive to steroids, cyclophosphamide can be added. Remission can be achieved in over 90% of patients treated with steroids or steroids/ cyclophosphamide (121).

Prognosis

Ninety percent of treated patients survive 1 year, and the 5-year survival rate is 62%. Overall prognosis correlates with the initial disease severity (127).

Small Vessels Vasculitis Not Associated with Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody (ANCA–)

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is most commonly observed in children aged 4 to 11 years but can occur at any age. It is the most common vasculitis in children.

HSP is a systemic vasculitis with immunoglobulin A (IgA)–dominant immune deposits affecting small vessels (capillaries, venules, or arterioles). Skin, gut, and glomeruli are typically affected. Arthralgias or arthritis are usually present.

Clinical features include nonthrombocytopenic palpable purpura predominant in dependent areas, lower limbs, and buttocks. Fever, arthritis, and arthralgia are present in over 70% of cases.

GI symptoms include abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea, which are found in 68% of patients.

Kidneys are affected in half of HSP patients (hematuria, proteinuria). Kidney biopsy reveals IgA-associated glomerulonephritis (128).

Laboratory investigations reveal elevated ESR and leucocytosis and elevated serum IgA levels in one third of patients. Biopsy of the skin or kidneys documents IgA immune deposits, which are found in vascular walls; sometimes, deposits of IgG and C3 are also found.

HSP is an idiopathic leukocytoclastic vasculitis and should be distinguished from vasculitis related to infections, which especially can follow bacterial infections (group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus). Recently, however, HSP has been linked with Bartonella henselae infection (129).

Long-term prognosis of HSP is determined by renal involvement. Patients with nephrotic syndrome, decreased factor XIII activity, hypertension, and renal failure at onset have an increased risk of developing chronic renal failure (130).

Buerger’s Disease—Thromboangiitis Obliterans

Thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO) is a non-necrotizing vasculitis of small- and medium-sized arteries and veins. TAO is called Buerger’s disease, after Leo Buerger, who gave a detailed description of a series of patients with TAO in 1908.

This inflammatory vascular disease mainly affects young male smokers; however, incidence in women seems to have risen from the previously reported 1% to 20% (133,134). TAO is encountered throughout the world but is more prevalent in Asia and Eastern Europe. The incidence of Buerger’s disease is declining in the world for unexplained reasons and is only partially related to a decline in smoking. According to the Mayo Clinic, the incidence of TAO has fallen from 104.3 in 100,000 people in 1947 to 12.6 in 100,000 people in 1986 (135). Similar trends have been reported from other countries (136,137).

Etiopathogenesis of TAO is not fully understood; however, there is striking relation to tobacco smoking. Virtually all TAO patients are tobacco smokers, and the activity of the disease is closely related to smoking patterns (138). Hypersensitivity to tobacco antigens, autoimmune mechanisms, and genetic predisposition may play a role in TAO development (139). The histopathological picture of affected vessels is characteristic and diagnostic. However, biopsy is not frequently utilized in clinical practice because of reluctance to biopsy ischemic tissue and because of the typical clinical presentation. Specimens for histopathological diagnosis usually are obtained from an amputated limb. Histopathological examination of affected vessels in TAO reveals non-necrotizing panvasculitis with occlusive thrombus infiltrated with macrophages (pseudoabscess) (139).

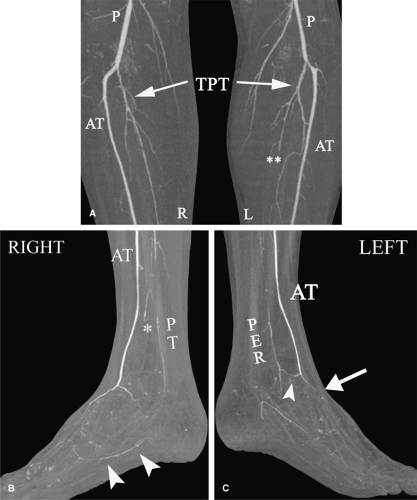

Classic clinical features are tobacco smoker (100%), age of onset <45 (90%), male gender (80% to 90%), distal ischemic ulcer/gangrene (50% to 90%), rest pain (50% to 90%), migratory superficial thrombophlebitis (40% to 60%), involvement of upper extremities (up to 90%), and Raynaud’s phenomenon (16% to 44%) (139). The majority of patients present with advanced disease and a relatively short history of foot/calf claudication, with quick progression to rest pain and gangrene. Physical examination reveals a lack of peripheral pulses, also frequently found on asymptomatic limbs, and a lack of proximal arterial bruits (otherwise atherosclerosis is suspected); active or resolved superficial thrombophlebitis, distal cyanosis, and toe/finger gangrene. Nonlimb arteries rarely are involved. Occlusions of visceral, coronary, and cerebral arteries are occasionally reported in TAO patients (140,141,142).

Differential diagnosis should include premature atherosclerosis, vasculitis, arterial embolism, and thrombophilia with arterial thrombosis.

Laboratory tests in TAO are usually normal. The diagnostic panel in TAO should include complete blood count, ESR, antinuclear antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies, hepatitis serology, and screening for hereditary thrombophilia.

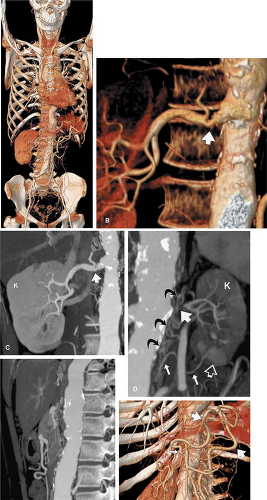

Angiography confirms arterial occlusion and may reveal characteristic vascular abnormalities. Angiographic findings in TAO are characteristic but not specific. Typical angiographic signs in TAO include (Fig. 10-8): multiple arterial occlusions (“skip lesions”) with normal, smooth nonaffected arteries; abrupt arterial occlusions; corkscrew collaterals; “direct” collaterals (Martorell sign); and “tree root” collaterals (139,143,144).

Prognosis in TAO is strictly related to tobacco abstinence. Progression of TAO is halted in patients who abstain from smoking, and TAO recurs in patients who continue to smoke (138).

It is difficult for TAO patients to quit cigarette smoking. Tobacco cessation programs are indicated for a majority of TAO patients.

Pharmacological therapy should improve peripheral circulation and alleviate pain. Only prostanoid therapy was found to improve peripheral circulation and cause remission in patients with Buerger’s disease (145).

Bypass surgery is available for selected patients (146), with patency rates up to 88% after 10 years (147,148). Thrombolytic therapy can be successful in cases of recent thrombosis (149).

Behçet Disease

Behçet disease (BD) is a chronic inflammatory systemic disease occurring throughout the world, with the highest prevalence in the Mediterranean basin, Middle East, and Central and Eastern Asia (or along the Silk Road). It is a chronic disease with a relapsing and remitting course and multiorgan involvement. BD is significantly more common in males (approximately 10-20:1). BD onset may occur at any age but is most common in young patients, typically in the third decade of life.

Clinical Presentation

The hallmarks of the disease are recurrent oral and/or genital ulcerations (up to 100%). Cutaneous lesions (50% to 85%) (150), arthritis (7% to 60%) (150), ocular involvement (23% to 80%) (150,151), CNS involvement (3.5% to 40%) (150,152), GI disease (3% to 16%) (150,153,154), and cardiac disease (155) are also present. Cutaneous lesions beside genital ulcerations include erythema, papulopustular lesions, neurodermatitis, and pyoderma gangrenosum-like lesions (150,156,157). Ocular involvement (uveitis, marginal keratitis, iridocyclitis, retinal vasculitis) is common and may lead to blindness (151). Arthritis is common in BD and may present as monoarthritis, palindromic rheumatism, and seronegative rheumatoid arthritis (150,158,159). GI involvement BD includes colitis and ileocolitis (160), Budd-Chiari syndrome, mesenteric thrombosis, and involvement of the liver and pancreas. Patients may have chronic symptoms or present with acute abdomen or GI hemorrhage (150,153,154,161). Neurological presentation may include vasculitis with ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke (152,162), meningoencephalitis (163), encephalitis (164), cerebral sinus thrombosis (165,166,167), or a multiple sclerosis-like syndrome (168). Vascular involvement of veins and/or arteries was reported in 2% to 46% of patients with BD (150,169,170). Venous involvement was twice as common as arterial and included deep vein thrombosis, superficial thrombophlebitis, and superior and inferior vena caval thrombosis (169). Arterial involvement is less common, diagnosed in 1% to 11% of patients (169,171). Arterial lesions include aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms of large- and medium-sized arteries and arterial thrombosis occasionally mimicking Buerger’s disease (171,172,173,174,175).

Pulmonary involvement is not uncommon in patients with BD and is reported in 3% of cases (171). Pulmonary artery aneurysms and venous thromboembolism are the most common presentations (176,177). Cardiac involvement may include aortic valve insufficiency (178) and aneurysm of the sinus of Valsalva (179).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made mainly on the clinical presentation, because no specific diagnostic laboratory test exists. Diagnostic criteria proposed by International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease (180) are:

Presence of oral ulceration and

Minimum two of the following:

Genital ulceration

Typical eye lesions

Typical skin lesions

Positive pathergy test1 (181)

Differential diagnosis depends on the clinical presentation and should include other vasculitis syndromes, hereditary and acquired thrombophilia, and infections including HIV, herpesvirus, and HCV.

Etiopathogenesis

The etiology of BD is unknown. Autoimmune mechanisms and genetic factors are suggested. An association with HLA B51 and MICA gene polymorphism suggests a genetic predisposition (187,188,189). Recently, autoimmunity to alpha-tropomyosin was described in patients with BD (190).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree