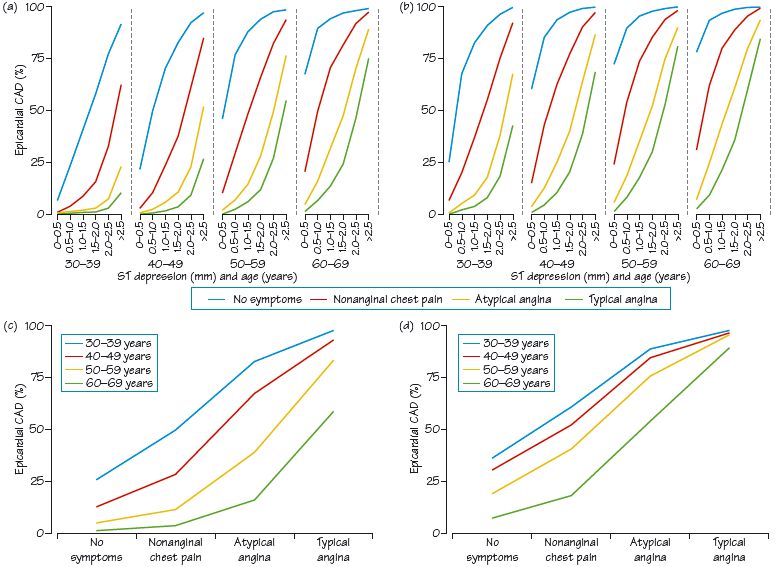

Fig. 64.2 Presence of epicardial coronary artery disease (CAD) related to age and sex (a) women, (b) men, (c) symptoms and (d) ECG changes.

Probably no test is as used and abused as the exercise stress test (EST). The test has four aims:

- To diagnose/rule out coronary disease. Compared to the ‘gold’ standard (coronary angiography) the EST has a sensitivity of 70% and a specificity of 80% (nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging has a higher sensitivity at = 85%, and specificity at = 90%). The problems therefore in using the EST to diagnose ishaemic heart disease (IHD) are: (i) those with coronary disease may have a normal test; (ii) those without IHD may have an abnormal test, i.e. significant ST depression (due to female sex, left ventricular [LV] hypertrophy, digoxin or idiopathic). Thus, though the diagnostic role of the EST is useful, it does have major limitations.

- To estimate prognosis, probably its major function (see below).

- To objectively measure exercise capacity (often serially to document changes over time). This is a very helpful function, especially when there is variance between clinical findings and reported exercise capacity. Exercise stress testing combined with gas exchange measurement provides evidence as to the physical fitness of the subject.

- To provoke arrhythmias, useful in patients with effort related palpitations, especially in structural heart disease.

Indications

The indications for stress testing reflect the utility of the test, as outlined above. In practice, tests are usually carried out: (a) to determine whether someone with an intermediate probability of coronary disease and symptoms compatible with coronary disease actually has coronary disease (e.g. middle-aged men with a few risk factors, middle-aged women with substantial risk factors); (b) to assess prognosis in those known to have coronary disease, e.g. post-acute coronary syndrome (ACS) risk stratification.

Methods

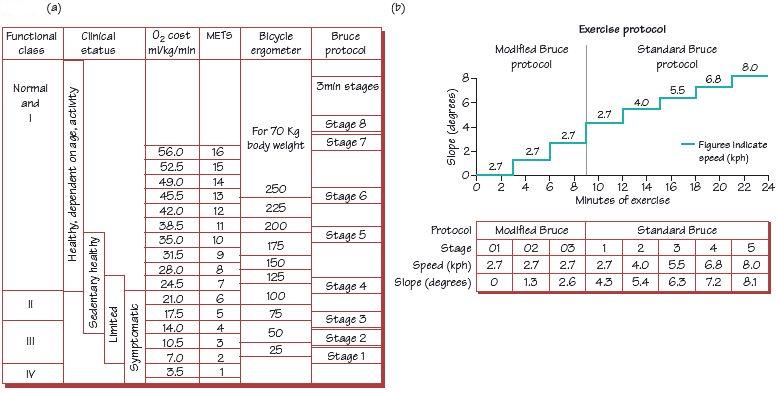

Most tests are performed using a motorized treadmill, which increases speed and inclination according to the protocol used. A static bicycle ergometer is occasionally used. Blood pressure (BP) is measured every few minutes. A 12-lead ECG is recorded at the start (lying and standing), every minute during the test, and for at least 5 min after the test (or longer until symptoms/ECG changes resolve). Patients exercise:

Interpretation

The interpretation depends on the pre-test probability of disease and the test findings:

- The greater the number of risk factors for coronary disease (especially age, but also male sex in the middle-aged, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, etc.) the greater the probability of coronary disease. The EST can alter this probability, but only rarely does it make coronary disease inevitable or impossible.

- Typical symptoms of myocardial ischaemia provoked by the test, regardless of any other test finding, increase the probability of coronary disease: the further symptoms are from typical angina the less likely is coronary disease.

- Exercise capacity is probably the single most important piece of data to come out of the stress test, and relates reasonably well to prognosis (see Duke score, a nomogram derived from Duke University, North Caroline, USA, Fig. 64.1a), regardless of whether coronary disease is present or not.

- ST depression: the greater the ST depression, the more widespread, and the more downsloping (as opposed to upsloping or planar), the more likely coronary disease is to be present (see Fig. 14.1b). ST depression confined to the inferior leads has the weakest relationship to coronary disease, if this extends laterally, the probability of IHD increases, and if this extends anterolaterally (especially if V3 is involved) the probability becomes quite high. Typical ‘ischaemic’ changes occurring in the first minute following exercise (Fig. 16.1) increase the probability of IHD further. ST changes on the pre-test ECG lower the significance of any exercise induced ST depression.

Implications

A high-level (i.e. ≥ end of stage III of the Bruce protocol) negative (i.e. no ST changes or symptoms) EST is associated with a very good outlook. In the absence of intrusive symptoms further tests for coronary disease are usually not required. A low-level (i.e. stage I or II) positive test (i.e. ≥ 2 mm ST depression with typical angina symptoms) is associated with a reduced outlook, and normally leads on to coronary angiography. Intermediate tests either lead on to nuclear myocardial perfusion scans (thallium or myoview) (few symptoms) or coronary angiography (the more symptomatic, those with more risk factors or impaired LV function).

Risks and complications

The risk of death is 1 per 10 000 in outpatients, 3 per 10 000 with a recent myocardial infarction (MI). There is a higher risk of inducing MI, arrhythmias (SVT, AF and VT/VF). To minimize risks, it is important to avoid EST in those with symptomatic aortic stenosis, ≤ 2 days from a small MI, ≤ 5–7 days from a larger MI, ACS with ongoing chest pain (i.e. chest pain within 48 h), uncontrolled heart failure, uncontrolled arrhythmias (e.g. AF with a fast heart rate response), febrile patients, gross hypertension (≥ 200/120 mmHg) or in haemodynamic disturbance (e.g. due to pulmonary embolism).

Fig. 64.3 (a) Exercise protocols, and equivalent clinical states and metabolic expenditure. (b) Bruce protocol exercise test.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree