Surgical Treatment of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Hartzell V. Schaff

INTRODUCTION

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a relatively common cardiac disease that may be defined as left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy in the absence of an underlying cause such as systemic hypertension or valvular aortic stenosis. Previously, the disorder was referred to as idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis (IHSS) or asymmetric septal hypertrophy (ASH), but the preferred term is HCM with or without obstruction. Approximately 1 in 500 individuals in the general population will be affected, and this translates into approximately 600,000 people in the United States.

As discussed below, the phenotypes and the clinical presentations of patients with HCM vary widely, and this has led to some confusion in the past about the importance of LV outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction and the indications for surgical treatment. On a molecular level, HCM is an autosomal dominant disease caused by genetic mutations coding for sarcomeric proteins and myofibrils. Over 400 mutations in more than 15 genes have been identified, and double and compound heterozygosity and homozygosity have been reported.

In an individual patient, the occurrence of HCM may be sporadic (20% to 40%) if it represents a new mutation or if there is incomplete penetrance in other family members. Among patients with positive family history, approximately 60% to 70% will have an identifiable HCM mutation by genetic testing. All HCM patients should have a thorough family history and pedigree analysis, preferably by a specialist in medical genetics, to identify and counsel relatives at risk. Genetic testing may be useful to identify specific mutations in the patient and relatives, but there is no clear role for genetic testing in risk stratification for patients known to have HCM.

PATHOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The diagnosis of HCM should be considered in any patient who has ventricular hypertrophy without an underlying cause, and most patients with HCM will have a maximal wall thickness ≥15 mm. The most common pattern of hypertrophy is diffuse involvement of the ventricular septum, and average maximal LV wall thickness is 20 to 22 mm. In 5% to 10% of patients, LV wall thickness is dramatically increased measuring 30 to 50 mm. Morphology of the septum varies according to age, and older patients with HCM often demonstrate a sigmoid configuration. Among children, increased LV wall thickness is defined as the thickness more than 2 standard deviations above the mean for age, sex, or body size (z score >2). These morphometric distinctions are not rigid, however, as patients have now been identified who are “genotype positive/phenotype negative” and may be considered to have subclinical HCM.

Other patterns of hypertrophy are recognized including mid-ventricular and apical HCM. It has been suggested that as many as one-third of patients with HCM will have segmental wall thickening involving only a portion of the ventricle and overall LV mass may be near normal. Importantly, the phenotype of the disease, the appearance, and severity of hypertrophy does not correlate with genotype, and multiple ventricular morphologies may be found in the same family.

Myocardial fiber disarray is the histologic feature of HCM, and myocytes show large, bizarre nuclei with degenerating muscle fibers and fibrosis. The disorganized whirling of muscle fibers is characteristic of HCM, but myocardial disarray is not pathognomonic for HCM and may be present in myocardium in any conditions in which there is pressure overload.

In the classic form of HCM with obstruction, the mitral valve, especially the anterior leaflet of the valve, moves anteriorly during systole, and the posterior leaflet closes against the mid- and free-edge third of the anterior leaflet instead of at the free edge as occurs normally. The free edge of the anterior leaflet is then displaced upward and narrows the LVOT. Anterior displacement of the valve leaflets produces mitral valve regurgitation (MR) of variable degree, and the jet is oriented in a posterolateral direction. Apposition of the anterior leaflet to the bulging septum produces a contact lesion, a whitish endocardial scar, which is useful in guiding septal myectomy. It is important to note that the occurrence of systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve is often dynamic, and provocative maneuvers such as Valsalva, squatting, exercise, and in some cases, adrenergic stimulation may be necessary to elicit SAM, MR, and LVOT obstruction.

Recently, Maron and colleagues reported that mitral valve leaflet length is increased in patients with HCM, an average of 7 mm for the anterior leaflet and 4 mm for the posterior leaflet. Although absolute leaflet length did not correlate with the presence or absence of LVOT obstruction, the authors did find that a ratio of anterior leaflet length to LVOT diameter of >2.0 was associated

with subaortic obstruction. The surgical implications of this finding are unclear, but it was suggested that the elongation of the mitral valve leaflets might constitute a primary phenotypic expression of HCM.

with subaortic obstruction. The surgical implications of this finding are unclear, but it was suggested that the elongation of the mitral valve leaflets might constitute a primary phenotypic expression of HCM.

Anomalies of papillary muscles are present in 15% to 20% of patients with HCM who undergo myectomy. These abnormalities include anomalous papillary muscles, direct insertion of papillary muscles into the anterior mitral valve leaflet, fusion of the papillary muscle to the ventricular septum or LV free wall, and accessory muscles and accessory anomalous chordae ( false chords). In most cases, these abnormalities do not complicate myectomy or contribute to outflow tract obstruction, but in some patients, anomalous papillary muscles, especially those that insert directly into the body of the anterior leaflet, can contribute to outflow tract obstruction.

Coronary arteries are larger than normal in patients with HCM, and basal coronary flow is increased at rest. In symptomatic patients with HCM, however, coronary flow reserve (CFR) is decreased compared with controls, and phasic flow is abnormal with a greater amount of flow during diastole. Decreased CFR is associated with a reduction in coronary resistance, suggesting that the mechanism is not due to narrowing of intramyocardial small arteries or compression of the microcirculation; indeed, the reduction in CFR in patients with HCM may be the result of near maximal vasodilation of the microcirculation in the basal state.

Atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD) is present in approximately 5% to 15% of patients with HCM depending upon the population studied, and at our clinic, significant CAD was detected in half of the patients who were selected for coronary angiography, and disease was severe in 26%. Survival of HCM patients with obstructive CAD is reduced compared with HCM patients without CAD, and survival is also poorer than patients without HCM who have comparable CAD and normal ventricular function.

Muscular bridging of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery is relatively common and has been identified in 15% of patients with HCM undergoing coronary angiography at our clinic. It is unclear whether bridging of the LAD plays a role in the pathophysiology of the disease and associated symptoms of angina, but for adult patients, risk of death and, in particular, sudden cardiac death are not increased among patients with HCM with myocardial bridging. In contrast, Yetman and coworkers reported that among children with HCM, systolic compression of LAD was present in 285 cases and was associated with a greater incidence of chest pain (60% vs. 19%; P = 0.04), cardiac arrest with subsequent resuscitation (50% vs. 4%; P = 0.004), and ventricular tachycardia (80% vs. 8%; P < 0.001). Myocardial ischemia was postulated to be the cause of this poor outcome.

The most important pathophysiologic feature of HCM is diastolic dysfunction with elevation of the LV end-diastolic pressure, which, in turn, increases left atrial and pulmonary venous pressures. These hemodynamic abnormalities account for the common symptoms of effort dyspnea and limited aerobic capacity. It is understandable, therefore, that atrial arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation (AF), may dramatically worsen diastolic filling when the ventricle is noncompliant and is dependent on atrial contraction.

Elevation of LV end-diastolic pressure is further aggravated by LVOT obstruction and by associated MR. Thus, while surgical myectomy has a minimal immediate effect on the overall LV mass, symptoms related to diastolic dysfunction are immediately improved when outflow gradients and MR are relieved. A secondary effect of septal myectomy on diastolic function is regression of hypertrophy.

A less common mechanism whereby LV hypertrophy led to diastolic dysfunction is the situation where concentric ventricular hypertrophy is so severe that muscle mass encroaches upon the ventricular cavity and reduces the normal cavity size. This is particularly striking in patients with the apical form of HCM where the distal one-third to distal one-half of the left ventricle may be obliterated (during diastole and systole) by muscle. Surgical remodeling by apical myectomy may increase end-diastolic volume and, thus, improve diastolic function.

In the past, there was debate on the importance of outflow tract obstruction as a mechanism for symptoms in patients with HCM. In many instances, outflow tract obstruction is labile, and previously, clinicians questioned whether catheter entrapment accounted for LVOT gradients measured during invasive catheterization. It is now recognized that outflow obstruction is much more common than previously thought. For example, Maron found resting outflow tract gradients of ≥50 mmHg in 37% of 320 patients with HCM and, more importantly, found exercise-induced gradients (mean 80 ± 43 mmHg) in an additional 106 patients. It appears, therefore, that as many as 70% of patients with HCM who come to clinical evaluation will have significant outflow tract obstruction. An important finding in this study was the relative unreliability of the Valsalva maneuver (sensitivity 40%) compared with exercise Doppler echocardiography in detecting these dynamic gradients. Latent obstruction can also be documented during hemodynamic catheterization by isoproterenol challenge, a technique that may be useful in patients who are unable to exercise or in patients in whom reliable Doppler echocardiography cannot be measured.

In patients with obstructive HCM, symptoms of dyspnea and fatigability may also relate to the severity of MR. As is true with LVOT obstruction, associated MR may be dynamic and difficult to appreciate in the resting state. Symptomatic patients with moderate or severe degrees of MR associated with HCM with obstruction are excellent candidates for septal myectomy because the MR and associated symptoms (dyspnea and fatigability) are almost always abolished or significantly improved with relief of LVOT obstruction.

MR that results from SAM is eccentric and directed posterolaterally during late systole. A centrally directed jet should raise suspicion of a primary leaflet abnormality contributing to valve leakage. Rupture of chordae with resultant leaflet prolapse can precipitate congestive heart failure, and hemodynamics may worsen if HCM is not recognized and patients are managed medically with afterload reduction. Preoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is unnecessary in most patients, but TEE is critically important intraoperatively in assessing the results of myectomy.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND NATURAL HISTORY

Many patients with HCM are asymptomatic, but most who come to surgical attention will have limiting symptoms. Typical symptoms caused by obstructive HCM are exertional dyspnea, chest pain (angina), and/or lightheadedness, especially light-headedness is associated with rapid change in posture. Although some patients present in childhood and adolescence, the most common clinical scenario for patients referred for septal myectomy is the development of symptoms in the fourth, fifth, or sixth decade of life. In most patients, it is the development of symptoms that leads to the diagnosis of HCM, and, thus, it is unknown whether LV outflow gradients existed previously. It seems likely, however, that in most patients, the development of symptoms corresponds to the development of subaortic obstruction. Occurrence of AF can also precipitate symptoms and predispose to systemic embolism, which occurs in 6% of patients. AF is found in 30% of older patients with HCM.

It is interesting to note that approximately one-third of patients with HCM who are symptomatic will have exacerbation of symptoms, predominantly dyspnea or presyncope, after meals. Postprandial symptom exacerbation is associated with higher resting LVOT gradients and advanced clinical symptoms.

In the general population, survival of patients with HCM is similar to survival of individuals without disease, and high mortality in HCM in earlier reports is likely due to excess numbers of high-risk patients included in studies from tertiary referral centers. More recent natural history studies indicate that the annual mortality rate of patients with HCM is approximately 1%, but there are several important subgroups that have higher risk of cardiac death. For example, HCM is the most common cause of sudden death among young athletes.

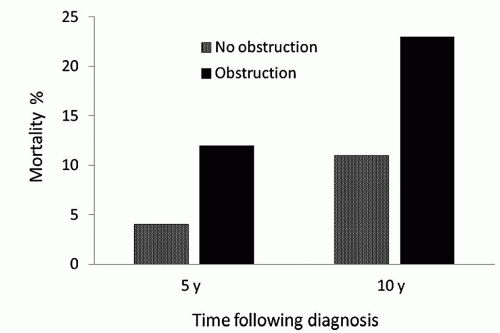

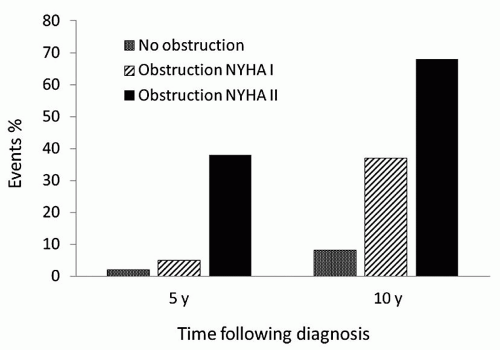

The importance of LVOT obstruction with regard to late outcome of patients with HCM has been controversial, but there is now substantial evidence that survival of HCM patients with outflow obstruction is reduced in comparison to patients without obstruction. Studies by Maron et al., Autore and associates, and Elliot and coworkers have demonstrated convincingly a strong correlation between resting outflow gradients and late risk of death. In a longitudinal follow-up of 1,101 patients with HCM, Maron et al. reported that patients with outflow tract obstruction (a basal gradient of at least 30 mmHg) had a risk of death from HCM or symptom progression that was more than four times that observed among patients without obstruction (Fig. 67.1). The association of outflow tract obstruction on limiting symptoms and death was independent of other clinical variables. Of note, patients with obstruction and mild symptoms (NYHA class II) were more likely to have progression to severe symptoms or to die from heart failure than asymptomatic patients with cardiomyopathy (Fig. 67.2).

Elliot et al. reported that risk of sudden death is relatively low (<0.4% per year) in asymptomatic patients with LVOT obstruction and none of the recognized risk factors for SCD, but their study did demonstrate reduced survival among patients with LVOT obstruction and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, abnormal exercise blood pressure response, a family history of premature sudden death, unexplained syncope, or severe LV hypertrophy.

The prognosis of patients with latent obstruction is less clear, but a study by Vaglio et al. suggests that the clinical course is similar to patients with resting obstruction. In their series, one-quarter of patients required invasive therapy for relief of symptoms, and annual mortality was 2% per year, a rate higher than that reported for patients with HCM and no LVOT obstruction.

Indications for Operation

Septal myectomy is, in general, reserved for patients who continue to have limiting symptoms despite medical treatment. Pharmacologic therapy usually begins with beta-adrenergic blocking agents, which have a negative inotropic effect and may mitigate latent outflow gradients provoked with exercise. Beta-blockers are less effective in reducing high resting gradients. The calcium antagonist, verapamil, has been used for patients with nonobstructive and obstructive HCM with the aim of improving ventricular relaxation and decreasing LV contractility, but hemodynamic and electrophysiologic side effects limit long-term use. Disopyramide has negative inotropic effects and is a type I-A antiarrhythmic agent that can improve symptoms by reducing resting gradients. However, this drug also has side effects including dry mouth and eyes, constipation, and difficulty in micturition. Also, it increases atrioventricular nodal conduction and thus may increase ventricular rate in patients

with AF. It is important to realize that while medications may ameliorate symptoms, drug therapy does not appear to decrease the probability of sudden death. In a recent study of 173 patients who were taking amiodarone, beta-blockers, verapamil, and/or sotalol for the treatment of symptoms, there was no difference in sudden death mortality compared with patients who were on no pharmacologic therapy.

with AF. It is important to realize that while medications may ameliorate symptoms, drug therapy does not appear to decrease the probability of sudden death. In a recent study of 173 patients who were taking amiodarone, beta-blockers, verapamil, and/or sotalol for the treatment of symptoms, there was no difference in sudden death mortality compared with patients who were on no pharmacologic therapy.

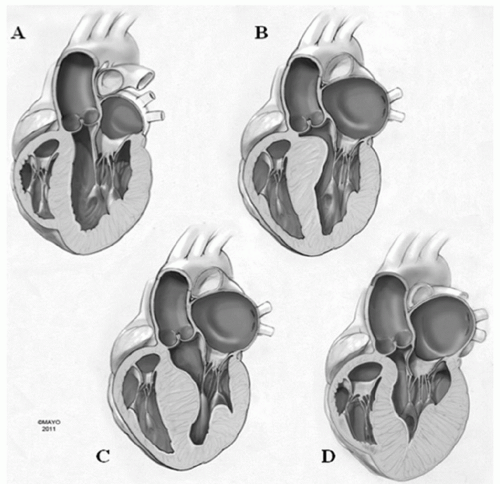

Although guidelines emphasize the importance of preliminary medical treatment before consideration of surgery, there are other important considerations regarding indications for septal myectomy in patients with obstructive HCM. Some patients (Fig. 67.3) have very favorable anatomy with localized hypertrophy in the subaortic septum and relatively normal wall thickness throughout the rest of the ventricle. In these patients, septal myectomy may be the preferred treatment rather than prolonged medical therapy because the results of surgery are so predictably good and relief of outflow tract gradient would be expected to relieve symptoms completely as there is little remaining substrate for diastolic dysfunction. Not infrequently, patients will prefer surgical treatment because of intolerance to side effects of medical treatment, especially side effects of high-dose betablockers. A final group of patients who might be considered earlier for surgical myectomy are patients who have high resting gradients (≥50 mmHg) and have a history of prior cardiac arrest or a strong family history of sudden cardiac death.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

SURGICAL TECHNIQUESA standard median sternotomy is preferred to provide adequate access both to the aorta and to the left ventricle. We favor normothermic cardiopulmonary bypass using a single, two-staged venous cannula and cold blood cardioplegia (initial dose of 1,000 to 1,200 ml) for myocardial protection. Adequate exposure of the subaortic septum is critically important, and several maneuvers facilitate the operation. Pericardial sutures are used only on the right side to elevate pericardium toward the surgeon and allow the left ventricle to fall posteriorly in the thorax. Next, an oblique aortotomy is made slightly closer to the sinotubular ridge than is usual for aortic valve replacement, and the incision is carried through the midpoint of the noncoronary aortic sinus of Valsalva to a level approximately 1 cm above the valve annulus. As illustrated in Figure 67.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree