*Based on clinical trials of LDL-C reduction to prevent primary or recurrent cardiovascular events in high-risk populations.

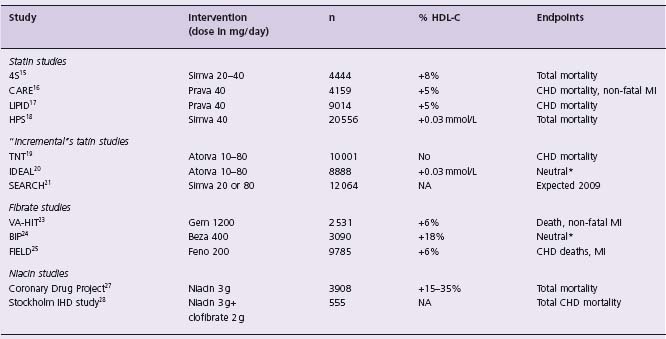

Table 75.2 Major high-risk studies of lipid-modifying therapies in high-risk patients.

*Primary endpoint not statistically significant. Combined secondary endpoints significant.20

Simva, simvastatin; Prava, pravastatin; Atorva, atorvastatin; Gem, gemfibrozil; Beza, bezafibrate; Feno, fenofibrate.

Question

Are further interventions warranted to further reduce cardiovascular risk?

Comment

This case is seen frequently in the secondary prevention setting. The patient is nearly at the LDL-C goal of <2.0 mmol/L. The argument can be made that in the absence of mortality benefit of lowering the LDL-C <2.0 in the TNT and IDEAL trials, the patient is treated according to the current standard of care. The low HDL-C remains problematic. There is presently a paucity of evidence supporting raising HDL-C pharmacologically on a background of statin treatment. This evidence is derived, in part, from post hoc analysis of large-scale studies or from pooled analysis of data. The approach to this patient must first involve lifestyle changes (cigarette cessation, quality of diet, weight reduction, exercise, and possibly moderate alcohol intake) which stand on their own merits, irrespective of their effects on HDL-C levels. Indeed, an elevated serum level of HDL-C might be considered a biomarker for cardiovascular health.

While each lifestyle change is expected to raise HDL-C by-5%, the cumulative effect of these changes may bring the HDL-C into the low-normal range for age and gender. Unfortunately, few patients implement such changes. Smoking cessation should be a priority of treatment in this patient. My own approach would be to further reduce LDL-C by optimizing the dose of statin. (Table 75.1) shows the expected effects of various pharmacologic manipulations including (1) keeping the current treatment, (2) increasing atorvastatin to 80 mg, (3) switching to rosuvastatin 40mg, (4) adding niacin (extended release) 2g, (5) adding fenofibrate 200 mg or (6) adding ezetimibe to ator-vastatin 40 mg.

While the lipoprotein profile is improved by the five additional options suggested here, the improvement is relatively small and the clinical significance is uncertain. Niacin extended release seems to have the most favorable improvement in both HDL-C and the Chol/HDL-C ratio. Increasing the statin dose is another option and favors monotherapy. It should be pointed out that of the options presented here, only statins (at either the maximal dose or used to decrease LDL-C <2.5mmol/L) are currently supported by evidence-based literature. The use of fenofibrate is less well supported by clinical trial data, especially in light of the FIELD trial. Other fibrates, especially gemfibro-zil, should not be combined with statins because of the risk of rhabdomyolysis. The addition of ezetimibe to statin monotherapy has the advantage of reducing LDL-C to a greater extent than simply doubling the dose of statin and avoiding side effects and adverse events associated with high- dose statins.

General comments on secondary preventive strategies

National guidelines for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease emphasize lifestyle changes (smoking cessation, quality of the diet, in terms of reducing saturated fats, weight reduction, physical activity and decrease in psychologic stress1-3. In this case, the immediate period following acute myocardial infarction was discussed, with emphasis on treatment and prevention of thrombotic episodes. Here, we will review an aspect of metabolic heart disease that is more controversial and much less supported by evidence- based medicine.

The data supporting lowering LDL-C for the prevention of recurrent events are well established and entrenched in clinical practice. Pharmacologic therapy is indicated to reach an LDL-C <2.0mmol/L and a Chol/HDL-C ratio <4.0. Aspirin is indicated in all subjects unless contraindicated. Beta-adrenergic blockers are indicated post myocardial infarction as are ACE inhibitors if the LVEF is decreased. A goal for HDL-C has not been set because of a lack of effective therapies to raise HDL-C and a lack of solid clinical evidence supporting raising HDL-C pharmacologically for cardiovascular disease prevention. While a low HDL-C is considered a categoric cardiovascular risk factor2-4 and is the most frequent lipoprotein disorder in premature CAD,5,6 there is still controversy surrounding the causal role of a low HDL-C in atherosclerosis. Experimental evidence shows that the atheroprotective effects of HDL extend far beyond removing cholesterol from lipid-laden macrophages in the atherosclerotic plaque, an effect known as the reverse cholesterol transport. HDL have anti-inflammatory effects, prevent oxidation of LDL, have antithrombotic properties, modulate vasomotor tone and may improve endothelial cell survival (by preventing apoptosis), migration and proliferation.7,8

Current approaches to raising HDL-C pharmacologically include statins, fibrates and niacin. Large-scale clinical studies using statins or fibric acid derivatives (fibrates) have shown a modest effect of these two classes of medication on HDL-C levels, usually in the order of 5–10%, much less than reported in smaller studies9 (Table 75.2). The drug torcetrapib, an inhibitor of cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), led to marked improvement in all lipoprotein classes when used with atorvastatin, but proved toxic in the large-scale clinical trial ILLUMINATE10 and showed no benefits on surrogate markers of atherosclerosis such as intravascular ultrasound11 or carotid intima-media thickness.12,13 Whether other CETP inhibitors will prove cardioprotective will have to be determined in appropriate clinical trials.

Effects of statins

Statins have a modest effect on HDL-C which may be mediated by the decrease in plasma triglycerides and an indirect effect on the transcriptional regulation of apolipoprotein AI (apo AI).14 There are presently six large-scale secondary or high- risk prevention trials that have examined the effect of statins on major cardiovascular events, coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality and total mortality15–20; the SEARCH trial21 will compare simvastatin 20 mg to atorvastatin 80mg. These findings are summarized in Table 76.2. Overall, the increase in HDL-C is modest, between 0% and 10%. The reduction in LDL-C is far more impressive and is considered to be a major factor in the reduction in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Meta-analysis of cholesterol reduction trials shows unambiguously the benefits of lowering LDL-C for cardiovascular disease prevention, especially in high- risk individuals.22 The results of these trials have been incorporated in national treatment guidelines for the prevention of CAD.1,2

Effect of fibrates

The use of fibrates for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases had led to more nuanced results. The VA-HIT trial showed a 22% reduction in major cardiovascular events with the drug gemfibrozil in patients with low HDL-C.23 Conversely, bezafibrate showed no benefits overall in patients post MI in an Israeli study.24 The FIELD study, in stable diabetic subjects, showed a neutral effect of fenofi-brate on cardiovascular endpoints.25 These studies showed potential benefits of fibrates in subgroup analysis which were, for the most part, not prespecified. Meta-analysis of fibrate trials, based on 17 studies,26 not including the FIELD trial, suggests that fibrates have a neutral effect on cardiovascular mortality. Generally, fibrates use will increase HDL-C by 5–15%, reduce triglycerides by 20–40% and cause a variable change in LDL-C. In moderate hyper-triglyceridemia, fibrates can cause an elevation in LDL-C, because of an increase in lipoprotein lipase activity and increased conversion of VLDL to LDL.

Effects of niacin

Only two relatively large trials, both predating the statin era, have studied the effects of niacin on cardiovascular outcomes. The Coronary Drug Project examined the effects of 3 g/day of nicotinic acid on CHD events.27 After 6.5 years, there was a reduction in CHD events, but not cardiovascular mortality. A post hoc analysis performed 10 years after the end of the study revealed a significant 11% reduction in total mortality, even when most patients were off study drug. The Stockholm Ischemic Heart Disease Study examined the combined effects of clofibrate 2 g/d with niacin 3 g/day in MI survivors. Total mortality was reduced by 26% and cardiovascular mortality by 36%.28 Niacin has broad and beneficial effects on all lipoprotein subclasses, including lipoprotein Lp(a).29 An in-depth analysis of all subsequent trials, most of which are angiographic regression studies or surrogate endpoints of atherosclerosis, and underpowered to evaluate cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, suggests that niacin has potent antiatherosclerotic effects.30 It should be noted that the currently recommended dose of niacin (either in a slow- or extended-release form) is 2 g/d. At this dose, one can expect an increase in HDL- C in the order of 20–25%, a reduction in LDL-C of 15–20% and a reduction in triglyc-erides of 20–30%, depending on baseline values.

Clinical trial evidence

Niacin has been used clinically for the past 50 years, since the observation by Canadian pathologist Aschtul that it can decrease total serum cholesterol.31 For many years, niacin was one of the few medications available to treat patients with dyslipidemias. The use of bile acid-binding resins and fibrates in the 1970s increased the physician’s armamentarium. However, the many side effects of niacin led to a decreased enthusiasm for its continued use in favor of statins which were first used in the mid 1980s. The side effects of niacin include flushing, now known to be caused by the release of pros-taglandin G2 by the Langerhans cells in the epidermis. Blocking the PgG2 receptor DP1 markedly decreases episodes of flushing and may make niacin easier to tolerate.32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree