Radiology of Mediastinal Masses

Evaluation of the mediastinum is an important part of the interpretation of a chest x-ray (CXR). Saying that it is important is not the same as saying that it is well done. The mediastinum is the giant blind spot of the CXR. Mediastinal masses in particular represent a significant challenge to the diagnostic capabilities of the radiologist. Plain-film analysis of mediastinal masses is considered, with pointers for differential diagnosis. The roles of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are also addressed.

Localizing Mediastinal Masses

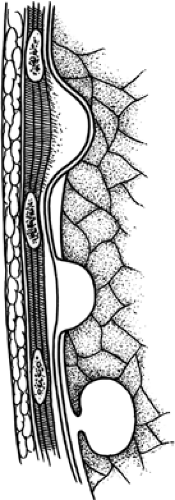

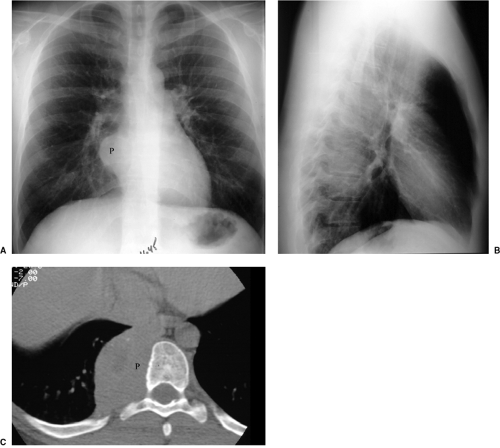

Localization of mediastinal masses on CXR is a two-part job. The first part is to determine that a mass is actually mediastinal, and the second part is to place it in the anterior, middle, or posterior mediastinum. Several signs place a mass in the mediastinum. Configuration of the interface of the mass with adjacent lung is sometimes helpful. Parenchymal lung masses are generally almost completely surrounded by lung, forming an acute angle with the mediastinum. Mediastinal masses instead have the shape of extraparenchymal masses, pushing toward lung with resultant obtuse angles (Fig. 9.1). As with lateral extraparenchymal masses, it may be very difficult to distinguish a mediastinal mass from one in medial pleura. Bone destruction (involving spine, ribs, or sternum) resolves the issue, indicating that a medial mass is mediastinal. Bilaterality of abnormality also strongly suggests a mediastinal origin (Fig. 9.2). Conversely, air bronchograms in a lesion indicate that it arose in lung, not mediastinum.

Bilaterality of abnormality in proximity to the thoracic midline suggests a mediastinal origin.

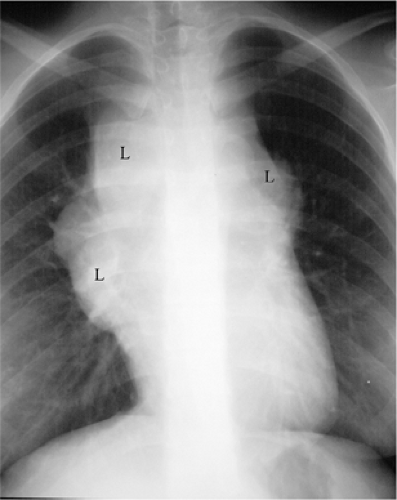

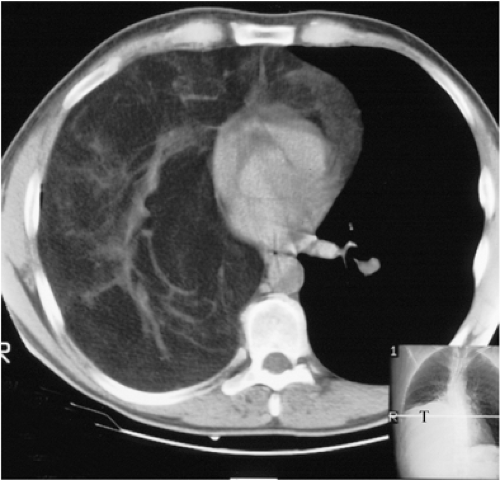

Cardiopericardial abnormalities constitute an important pitfall in diagnosis of mediastinal masses. On the one hand, a soft anterior mediastinal mass such as a thymolipoma may droop down along the heart border (Fig. 9.3), resembling pericardial effusion or cyst (1). On the other hand, a pericardial cyst or neoplasm may extend cephalad into the pericardial recesses, simulating a mediastinal mass. CT may be very helpful in this regard.

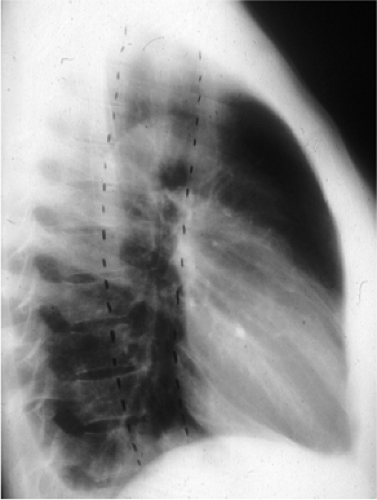

The ability of radiologists to localize mediastinal masses via CXR has atrophied because of CT. Certain signs (silhouette sign, hilum overlay and convergence signs, and cervicothoracic and thoracoabdominal signs) (Chapter 3) can be enormously helpful in localizing mediastinal masses. Effect of a mass on adjacent mediastinal structures (trachea,

paraspinal line, anterior and posterior junction lines, and ribs) should also be assessed. These observations, in combination, will often be more useful for localizing mediastinal masses than will lateral chest radiographs (Fig. 9.4). Although the advantage of having two right-angle radiographs for evaluating three-dimensional anatomy has previously been emphasized, lateral radiography is frequently not very helpful for mediastinal mass localization.

paraspinal line, anterior and posterior junction lines, and ribs) should also be assessed. These observations, in combination, will often be more useful for localizing mediastinal masses than will lateral chest radiographs (Fig. 9.4). Although the advantage of having two right-angle radiographs for evaluating three-dimensional anatomy has previously been emphasized, lateral radiography is frequently not very helpful for mediastinal mass localization.

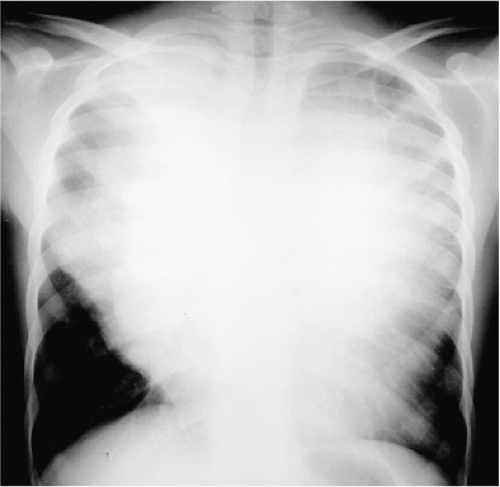

Figure 9.2 Large mass of uncertain origin. Extension into both hemithoraces is typical of a mediastinal mass, in this case Hodgkin disease. |

Figure 9.3 Thymolipoma fills the right hemithorax with fat and vessels. The computed tomography scout demonstrates that the mass (T) droops down toward the diaphragm. |

Differential Diagnosis

Generating a differential diagnosis for a mediastinal mass starts with a classification scheme. The system used by Felson (2) (Fig. 9.5) divides the mediastinum into anterior, middle, and posterior compartments by drawing one line along the front of the trachea and the back of the heart and a second line 1 cm posterior to the anterior margin of the thoracic vertebrae. This system does not classify the superior mediastinum as a separate compartment.

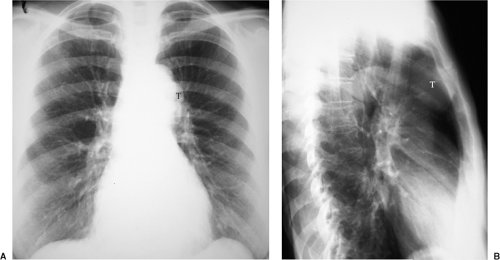

For anterior mediastinal masses, the classic differential diagnosis is the “4 Ts”: thymoma, thyroid, teratoma, and terrible lymphoma (Table 9.1). Further clues can be obtained from the radiographic appearance, the patient’s age, and associated clinical manifestations. For example, mediastinal thyroid is rare if there is not demonstrable direct extension from the neck. Calcification, teeth, and/or fat in a lesion favor teratoma. Lymphoma is the likeliest diagnosis when there is a multilobular mass (Fig. 9.6). Thymoma often (although not always) overlies the aortopulmonary window (Fig. 9.7).

The “4 Ts” delineate the important entities in anterior mediastinal mass differential diagnosis—thymoma, thyroid, teratoma, and terrible lymphoma.

Turning to clinical clues, teratoma is typically a disease of teenagers, whereas thymoma usually affects those aged 40 to 60 years. Hodgkin disease has a bimodal age distribution, particularly affecting patients in their teens or 20s and those over age 50. There are a number of clinical conditions associated with thymoma, including myasthenia gravis (MG), pure red cell aplasia, and hypogammaglobulinemia. MG is the most common of these, occurring in roughly 50% of patients with thymomas; among patients with MG, 10% to 15% have an underlying thymoma.

Figure 9.5 Compartments of the mediastinum. (From Felson B. Chest roentgenology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1973:419 , with permission.) |

Table 9.1: Anterior Mediastinal Masses | |

|---|---|

|

Figure 9.7 Thymoma. A. Posteroanterior chest x-ray: subtle mass overlying aortopulmonary window (T). B. Lateral chest x-ray: much more obvious mass (T). |

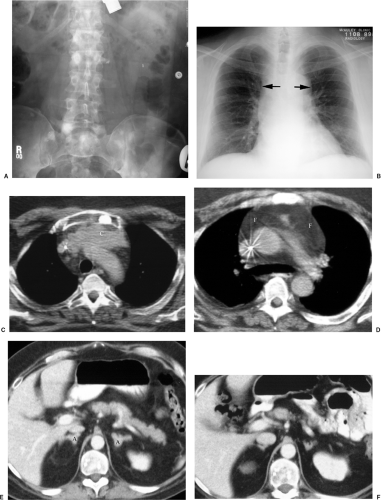

The classic mnemonic is not all inclusive. There are thymic lesions other than thymoma to consider, for example. Thymic carcinoid demonstrates some of the same features as bronchial carcinoid (Fig. 9.8). Metastatic disease and vascular lesions (such as aneurysms) can occur in any mediastinal compartment. Trauma or nontraumatic mediastinal hemorrhage probably affects the anterior mediastinum more than any other mediastinal compartment (Fig. 9.9). Finally, when parathyroid adenomas are not found in the neck, they usually occur in the anterior mediastinum (Fig. 9.10). Only a small percentage (less than 2%) of normal parathyroid glands are mediastinal, but in patients with previously unsuccessful neck exploratory surgery for primary hyperparathyroidism, the incidence of a mediastinal adenoma rises to 47% (3). Whereas most ectopic parathyroid glands are in the superior aspect of the mediastinum, readily accessible to a neck incision, the percentage of mediastinal glands requiring sternotomy rises to 17% in those being reexplored for hyperparathyroidism.

In patients with prior neck exploration and continued primary hyperparathyroidism, the incidence of mediastinal adenoma is 47%, and 17% of such glands cannot be reached from a neck incision.

Turning to the middle mediastinum (Table 9.2), the key structure that traverses this compartment from top to bottom is the esophagus (Fig. 9.11). As a result, even in the twenty-first century CT is not the only alternative to the CXR for diagnosis and further characterization of middle mediastinal masses. Barium swallow actually is better than CT at delineation of esophageal lesions, which account for many middle mediastinal masses. In fact, it is surprising how many patients with documented esophageal carcinomas have normal or nearly normal chest CTs. Other esophageal masses (such as leiomyomas) are similarly better seen with barium swallow than with CXR or CT.

If a middle mediastinal mass is unrelated to the esophagus, the differential diagnosis includes bronchogenic cyst (Fig. 9.12), lymph node abnormalities (sarcoid, lymphoma, metastases), and vascular lesions (Fig. 9.13). Bronchogenic cyst most often occurs between the carina and the esophagus, but the right lower paratracheal region is not an uncommon alternative location (Fig. 9.14). Among lymph node diseases, tuberculous lymphadenitis has become a more important entity because it is common in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and frequently involves middle mediastinal lymph nodes. Metastatic disease usually affects lymph nodes in the anterior and/or middle mediastinum. Lung cancer is the most common primary neoplasm to involve mediastinal lymph nodes. Most extrathoracic neoplasms do not commonly metastasize to intrathoracic

lymph nodes, but there are exceptions. Head and neck tumors, genitourinary neoplasms (especially testicular and renal cell carcinomas), breast carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, and melanoma are extrathoracic primaries with a predilection for hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes.

lymph nodes, but there are exceptions. Head and neck tumors, genitourinary neoplasms (especially testicular and renal cell carcinomas), breast carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, and melanoma are extrathoracic primaries with a predilection for hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes.

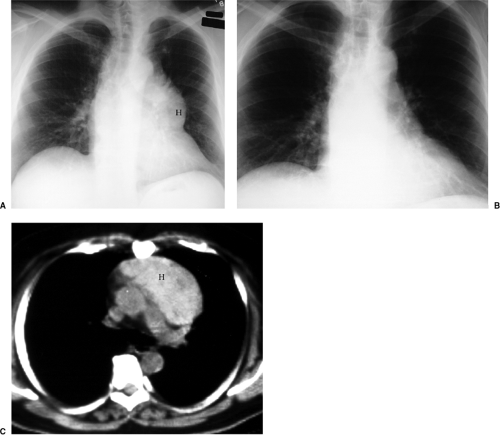

Figure 9.9 Disappearing anterior mediastinal mass. A. Posteroanterior chest x-ray 3-27: anterior mediastinal mass (H) blends with left heart border. Note the hilum overlay sign, with vessels converging medial to the mass border. B. Posteroanterior chest x-ray 4-1: mass no longer present. C. Noncontrast computed tomography 3-28: high attenuation of the mass (H) reveals that it is spontaneous mediastinal hemorrhage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|