Infections in the Immunocompromised Host

Immunocompromised hosts have altered immune mechanisms, either cell mediated or humoral, and are predisposed to opportunistic infections. Pulmonary infections constitute an important category of major complications in the immunocompromised host. Almost all human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients will suffer at least one respiratory illness over the course of their disease (1). The incidence of pulmonary infections in other forms of immune compromise varies. Approximately 50% of bone marrow transplant recipients (2) and 80% of acute leukemia patients will develop pneumonia (3).

The radiologist plays a critical role in the diagnosis and monitoring of pulmonary infections. This includes detection and analysis of abnormalities on the chest radiograph (CXR), generating an appropriate differential diagnosis, and monitoring disease progression, response to treatment, and complications. The radiologist should recommend further evaluation with computed tomography (CT) and high resolution CT (HRCT) when needed and should guide appropriate interventional procedures such as fiberoptic bronchoscopy, open lung biopsy, and CT-guided biopsy. The different pulmonary infections related to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and to other forms of immune compromise are the subject of this chapter.

Pulmonary Manifestations of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Approach

HIV-infected patients suffer from a variety of lung infections and neoplasms. Several factors are crucial in making the correct diagnosis. The CD4 count is a measure of a patient’s immune status and is predictive of which pulmonary manifestation will be encountered (Table 6.1). For example, cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections are encountered in patients

with CD4 counts under 20 cells/mm3, whereas Nocardia pneumonia and Kaposi sarcoma are encountered when the count is less than 200 cells/mm3 (4).

with CD4 counts under 20 cells/mm3, whereas Nocardia pneumonia and Kaposi sarcoma are encountered when the count is less than 200 cells/mm3 (4).

The CD4 count is a measure of immune status that helps to predict which infections are likely.

Table 6.1: CD4 Counts in AIDS—Correlation with Associated Diseases | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Patient demographics also help to determine likely pulmonary manifestations (Table 6.1). Intravenous drug abusers are more likely to suffer infections such as Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia, septic emboli, and tuberculosis (5), whereas CMV infections are more frequent in patients infected by HIV through sexual contact (6).

Prophylactic antimicrobial therapy decreases the likelihood of infection with drug-susceptible organisms (4) but may delay diagnosis by interfering with blood and sputum culture results (7). Integration of the radiographic appearance with demographic data, laboratory results, and clinical presentation is necessary to reach a reasonable differential diagnosis (8).

Bacterial Infections

AIDS patients have altered B-cell function and are therefore susceptible to severe infections by encapsulated bacteria, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Hemophilus influenza, with any CD4 count (9). As the CD4 count falls, the susceptibility to bacterial infection increases (10). The introduction of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) prophylaxis has increased the incidence of bacterial pneumonia relative to that of PCP (10). Intravenous drug abusers are at greater risk to develop S. aureus pneumonia, septic emboli, and empyema (5).

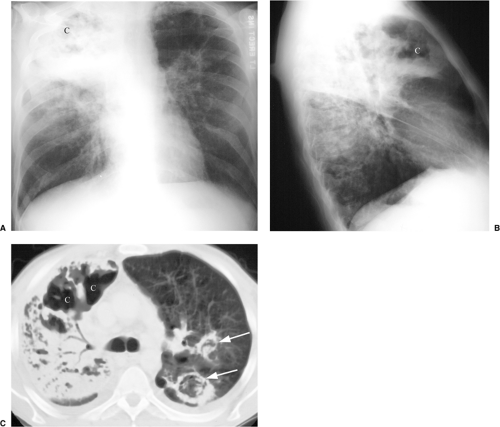

Bacterial pneumonia typically presents with segmental or lobar airspace disease. In patients with AIDS there is a higher incidence of multilobar pneumonia (4) and of rapid progression and cavitation (7) (Fig. 6.1) than in non-immunocompromised hosts. Pyogenic airway disease with bronchitis, bronchiolitis, and bronchiectasis is common in HIV-infected

patients with normal CD4 counts. The radiographic findings are subtle and include bronchial wall thickening on the CXR and tree-in-bud opacities, bronchiectasis, bronchial wall thickening, and mucoid impactions on HRCT (11).

patients with normal CD4 counts. The radiographic findings are subtle and include bronchial wall thickening on the CXR and tree-in-bud opacities, bronchiectasis, bronchial wall thickening, and mucoid impactions on HRCT (11).

Mycobacterial Infections

Tuberculosis

The estimated infection rate with Mycobacterium tuberculosis among HIV-infected patients is 5%. The rate is higher among specific groups such as Latinos, African Americans, and intravenous drug abusers (12). Because tuberculosis is a highly contagious and treatable disease, it needs to be recognized promptly (13).

A typical finding of tuberculosis in AIDS patients is low attenuation lymph nodes with enhancing rims.

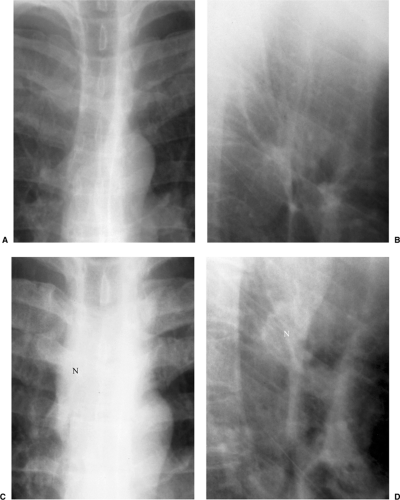

The clinical presentation and radiographic appearance are influenced by immune status and CD4 level. With CD4 counts below 350 cells/mm3, reactivation of dormant M. tuberculosis may occur (8). Findings will be similar to reactivation tuberculosis in immune competent hosts, with upper lobe predominant exudative and cavitary disease. Pleural effusions in AIDS patients are more prevalent and tend to be bigger, with a higher inoculum of bacteria (14). When the CD4 counts drop below 200 cells/mm3, the

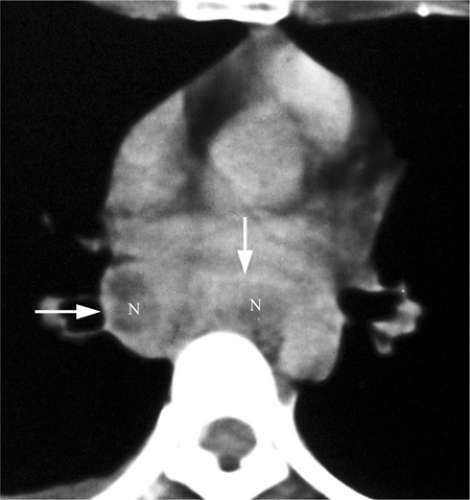

radiographic appearance is more like primary tuberculosis, with randomly distributed focal airspace disease, diffuse infiltrates, miliary nodules, and/or multiple pulmonary nodules. Cavitation is rare in this setting (15). Bulky hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement are typical in HIV patients (Fig. 6.2), unlike in non-AIDS patients. On enhanced CTs lymph nodes may demonstrate low attenuation centers with enhancing rims (16) (Fig. 6.3).

radiographic appearance is more like primary tuberculosis, with randomly distributed focal airspace disease, diffuse infiltrates, miliary nodules, and/or multiple pulmonary nodules. Cavitation is rare in this setting (15). Bulky hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement are typical in HIV patients (Fig. 6.2), unlike in non-AIDS patients. On enhanced CTs lymph nodes may demonstrate low attenuation centers with enhancing rims (16) (Fig. 6.3).

Atypical Mycobacteria

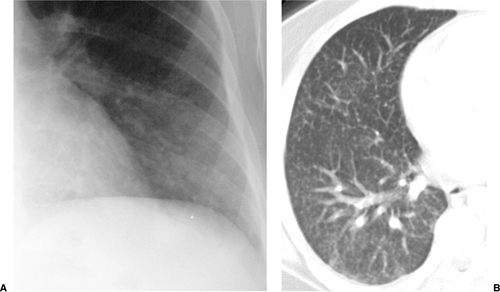

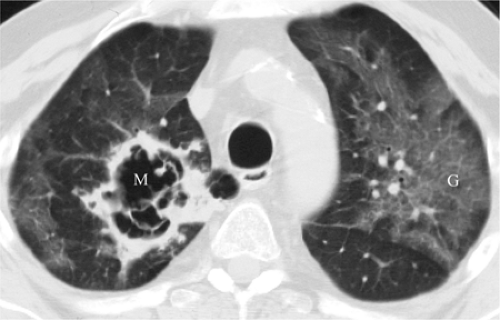

Mycobacterium avium complex infection occurs in severely immunocompromised patients, with CD4 counts less than 50 cells/mm3. Disease is disseminated throughout the reticuloendothelial system and may involve the lungs as well. Disease tends to be subacute, with constitutional symptoms (4). The radiographic appearance ranges from a normal CXR to large pulmonary nodules that may cavitate, often with lymph node enlargement (17,18). On HRCT there is a tendency for bilateral lower lobe distribution and ground glass opacities (GGOs) (19). Other forms of atypical mycobacteria are rare (Fig. 6.4).

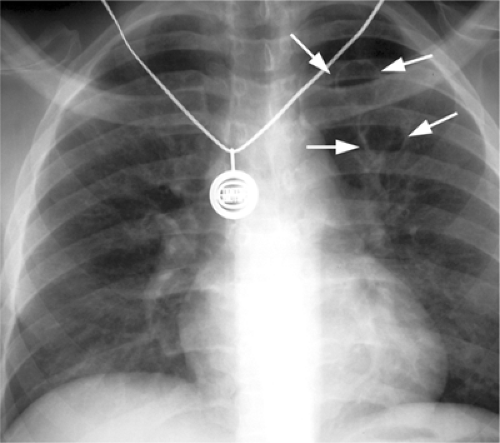

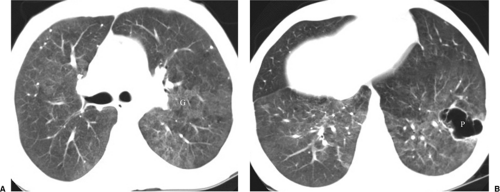

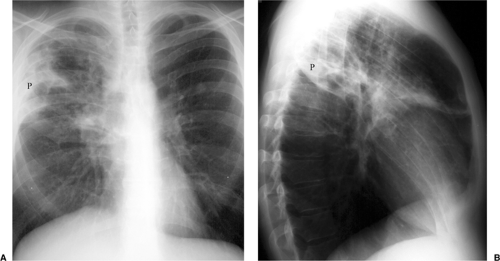

Figure 6.4 M. kansasii in AIDS (CD4 count = 23). (A) Posteroanterior and (B) lateral chest radiograph: cavitary upper lobe pneumonia (P), especially involving the right upper lobe. |

Fungal Infection

Fungal pneumonia is uncommon in AIDS patients because neutrophil activity is preserved. Patients receiving antiviral therapy that induces granulocytopenia are susceptible to fungal infections (7) (Fig. 6.5). The common pathogens causing fungal pneumonia are Cryptococcus and Aspergillus. Cryptococcus is a fungus that commonly causes meningitis. The radiographic features of Cryptococcus pneumonia include nodular interstitial infiltrates, solitary or multiple pulmonary nodules or masses that may cavitate, pleural effusions, and lymph node enlargement (20). The radiographic appearance of Aspergillus is discussed later in this chapter (Fig. 6.6).

Pneumocystis carinii Pneumonia

P. carinii is a unicellular organism that behaves like a protozoan but is classified as a fungus (21). The organism cannot be grown in cultures, and therefore the diagnosis is based on visualizing the organism (or its cyst) in special stains preformed on sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. PCP can occur at any level of immunosuppression, but it becomes common when CD4 counts are at or below 200 cells/mm3. Despite the use of effective prophylactic therapy and the resultant decline in PCP, it remains the most common opportunistic pulmonary infection in AIDS. Approximately 70% of AIDS patients will suffer at least one PCP infection during the course of their disease. It is more common in homosexual and male patients (21,22). PCP in AIDS patients is insidious and presents with nonproductive cough, dyspnea, low-grade fever, and malaise (8).

Pneumocystis remains the most common opportunistic pneumonia in AIDS, ultimately affecting roughly 70% of AIDS patients.

The radiologic manifestations of PCP are varied. In most cases it presents as bilateral, diffuse, symmetric parenchymal abnormality with a perihilar and basilar predominance (Fig. 6.7). Early findings are often subtle, and the CXR is normal or nearly normal in anywhere from 10% to as many as 39% of patients (8). Infection may appear as interstitial granular or reticular opacities or as airspace disease. Without treatment PCP often progresses to confluent airspace disease (22,23). Upper lobe disease is classically seen in patients receiving aerosolized prophylactic pentamidine therapy (23). Radiographic improvement is expected within 10 days of appropriate treatment, although there is usually initial radiographic worsening due to capillary leak. Atypical manifestations are encountered in approximately 5% and include isolated lobar disease, focal parenchymal opacities, nodules and masses, a miliary pattern, endobronchial lesions, and pleural effusions (23).

AIDS patients may present with cystic lesions (Fig. 6.8), thin or thick walled, regular or irregular in shape, that may be surrounded by GGOs (Fig. 6.9), indicating inflammatory pneumonitis. This form of disease is termed cystic PCP and is rare in non-AIDS patients (21,23). The cystic lesions show a predilection for the lung apices and subpleural

areas, and patients present with spontaneous pneumothorax in 6% to 7% of cases (Fig. 6.10). The pneumothoraces are frequently bilateral, associated with a higher mortality rate of 33% to 57%, and not always responsive to standard chest tube placement (21).

areas, and patients present with spontaneous pneumothorax in 6% to 7% of cases (Fig. 6.10). The pneumothoraces are frequently bilateral, associated with a higher mortality rate of 33% to 57%, and not always responsive to standard chest tube placement (21).

Figure 6.7 Pneumocystis pneumonia in AIDS (CD4 count = 27). Widespread bilateral parenchymal abnormality with perihilar confluent airspace disease, left greater than right. |

Chest CT and HRCT are helpful for the patient with a nonspecific clinical presentation and normal or near normal CXR or when PCP relapse is suspected in the presence of an abnormal CXR from a previous episode of infection (21). At HRCT, PCP manifests as GGOs that may be diffuse and homogeneous or patchy and geographic in distribution, often in the perihilar lungs (7,21). GGO is attributed to accumulation of fluid, organisms, and debris within the alveoli and is considered highly suggestive of P. carinii infection in the setting of HIV infection (Figs. 6.6, 6.9, and 6.10). HRCT may show thickening of interlobular septa secondary to edema and cellular infiltration and may delineate the extent and distribution of cyst formation and changes of interstitial fibrosis secondary to chronic PCP. CT findings may suggest an alternative diagnosis, an additional diagnosis along with PCP (Fig. 6.6), or another pathogen and may help to direct a biopsy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree