Pulmonary Manifestations of Systemic Diseases

Many systemic diseases have thoracic manifestations. In some patients the initial presentation of the disease can be abnormality on chest x-ray (CXR) or chest computed tomography (CT). Only some of the more common diseases are covered in this chapter.

Collagen Vascular Disease

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is usually insidious in onset, marked by ill health and chronic joint deformity. It has a prevalence of up to 2%, an age at onset of 25 to 55 years, and a male-to-female ratio of 1:3. Rheumatoid factor is positive in 50% to 70% of patients. The term “rheumatoid disease” may be more appropriate. Although the brunt of disease falls on the joints, this is a systemic connective tissue disease with extraarticular manifestations (pulmonary, cardiac, vascular, reticuloendothelial, hematologic, renal, and ocular) in up to 76% of patients (1,2,3,4,5,6,7). Rheumatoid lung disease affects 2% to 54% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, with a male-to-female ratio of 5:1. The manifestations may be subdivided into eight categories (Table 13.1.).

Although rheumatoid disease has a 3:1 female predilection, rheumatoid lung disease has a 5:1 male-to-female ratio.

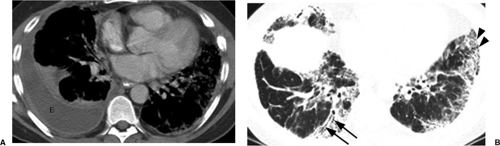

Pleural abnormalities are most frequent (Fig. 13.1A), manifesting as unilateral exudative pleural effusion in 90% of patients and sometimes demonstrating little change over months. Bilateral large effusions can be seen. For pleural disease, the male-to-female ratio is 9:1 (5). There are usually not other pulmonary rheumatoid changes. Pleural disease may antedate the onset of arthritis. The effusion is an exudate with protein content greater than 4 g/dL, a low glucose content (less than 30 mg/dL), and no rise in pleural glucose during intravenous glucose infusion (as opposed to tuberculosis, which also has low pleural fluid glucose). There is generally a low white cell count with many lymphocytes, and pleural fluid is usually positive for rheumatoid factor, lactate dehydrogenase, and rheumatoid arthritis cells (8). Pleural thickening may also occur, usually bilaterally. Pleural fibrosis

and adhesions are often found at autopsy. Pneumothorax can occur secondary to rupture of a rheumatoid nodule or end-stage fibrotic lung disease.

and adhesions are often found at autopsy. Pneumothorax can occur secondary to rupture of a rheumatoid nodule or end-stage fibrotic lung disease.

Table 13.1: Radiologic Manifestations of Rheumatoid Arthritis | |

|---|---|

|

Diffuse interstitial fibrosis is seen in 2% to 6% (8), most frequently with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. It causes a restrictive ventilatory defect with deposition of IgM in alveolar septa and has a lower lobe predominance. The radiographic findings are often indistinguishable from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis or usual interstitial pneumonitis (Fig. 13.1B). Irregular linear opacities, honeycombing, or a reticulonodular pattern are seen in the lower lobes and occasionally more cephalad. High resolution CT (HRCT) has greatly improved early detection of fibrosis with inter- and intralobular septal thickening and patchy ground glass opacity, mainly in a subpleural distribution. As disease progresses, it eventually results in honeycombing. It is thought that rheumatoid lung disease is more benign than usual interstitial pneumonitis (7,8,9).

Necrobiotic nodules are identical to subcutaneous nodules. They are well-circumscribed masses in the lungs, pericardium, and visceral organs and are associated with advanced rheumatoid disease. They are a rare manifestation in the lungs. They are usually multiple and noncalcified, measuring 3 mm to 7 cm in size. They are commonly located in the lung periphery. Nodules may cavitate, typically with a thick wall and a smooth outline. They are often found in conjunction with subcutaneous nodules that wax and wane with the activity of the disease (1,3,7,8,9).

Caplan syndrome consists of multiple nodules due to hypersensitivity reaction to irritating coal dust particles in the lungs of coal miners with rheumatoid. Appearances are similar to necrobiotic nodules without pneumoconiosis. These well-defined nodules of 5 mm to 5 cm may develop rapidly. They tend to appear in clusters, predominantly in the upper lobes and in the lung periphery. Nodules may remain stable but may increase in

number, may calcify, or may resolve completely. There is no relationship between severity of arthritis and extent of nodules.

number, may calcify, or may resolve completely. There is no relationship between severity of arthritis and extent of nodules.

Bronchial abnormalities such as bronchiectasis or bronchiolitis obliterans occasionally occur. Pulmonary arteritis is a rare manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis, with fibroelastoid intimal proliferation of the pulmonary arteries that may result in pulmonary arterial hypertension and/or cor pulmonale (8). Cardiopericardial silhouette enlargement is also unusual and may result from pericarditis with pericardial effusion or myocarditis causing congestive cardiac failure.

Various bone abnormalities may be seen on the CXR. This includes arthritis of visualized joints, ankylosis of vertebral facet joints, and vertebral body collapse secondary to steroid therapy.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has an incidence of 1 in 2,000, a typical age at onset between 20 and 40 years, and is nine times more common in females than males. It is common in the United States and East Asia, and the incidence is greater in African Americans. Among African-American women the incidence approaches 1 in 250, and disease often has a more severe course. There is an increased incidence of the human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) B8 and DR3. SLE may be exacerbated by sunlight and infection, and a lupus-like syndrome is induced by certain drugs such as hydralazine, oral contraceptives, phenothiazines, and procainamide. The most common early features are fever, arthralgia, general ill health, and weight loss. A characteristic manifestation is the “butterfly” rash on the face, although this does not have to be present. Antinuclear antibodies are present in 95%. The presence of antibodies to double-stranded DNA is diagnostic, although Sm antibodies are more specific for SLE. Hypergammaglobulinemia occurs in 77%, lupus erythematosus (LE) cells in 80%, and a false-positive Wasserman test for syphilis in 24%. SLE affects the joints in 90% of patients, the skin in 80%, the kidneys in 60%, the lungs in 50% to 70%, the cardiovascular system in 40%, the nervous system in 35%, and also the blood and lymphatic system (1,2,5,6,7). SLE affects the respiratory system more commonly than any other connective tissue disease, with radiologic abnormalities listed in Table 13.2.

SLE affects the respiratory system more commonly than any other connective tissue disease.

Radiographically, the acute form (lupus pneumonitis) is characterized by poorly defined areas of ground glass opacity or consolidation peripherally at the lung bases. In the chronic form there is basal interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, seen in approximately 3% of patients (Fig. 13.2) (5). Bibasal fleeting plate-like atelectasis secondary to infection or infarction can also occur. Alveolar hemorrhage may manifest as ground glass opacity or consolidation. Patients with SLE have an increased incidence of pulmonary emboli secondary to circulating antiphospholipid antibodies. Pulmonary infections due to immunosuppressive therapy are also seen (10,11).

Table 13.2: Radiologic Manifestations of SLE | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Pleural effusion is the most common radiographic manifestation (Fig. 13.3), with recurrent small bilateral pleural effusions in 70%. Pleural thickening may also occur. Pericardial effusion from pericarditis is also common. Cardiomegaly from primary lupus cardiomyopathy is a rare manifestation (10,11).

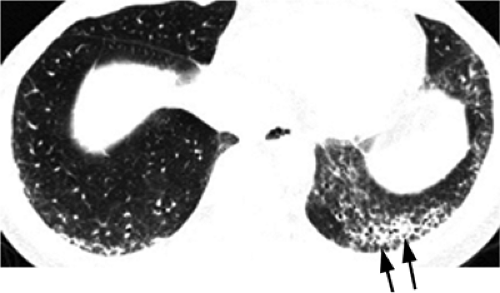

Figure 13.2 Systemic lupus erythematosus. High resolution computed tomography with basilar fibrotic disease, worst in the left lung (arrows). |

Progressive Systemic Sclerosis or Scleroderma

Scleroderma has an incidence of 2 to 12 per million, a typical age at onset of less than 45 years, and a male-to-female ratio of 1:3. It is a systemic disease with atrophy and sclerosis of the skin, gastrointestinal tract, musculoskeletal system, lungs, and heart. There is an association with primary biliary cirrhosis. Blood vessels show arteritis and thickening. Generally, the clinical presentation includes fever, lassitude, and weight loss. Antinuclear antibodies are present in 30% to 80%. Anti-topoisomerase or antiScl-70 is present with diffuse cutaneous involvement; anti-centromere antibody is present in one-third of patients with progressive systemic sclerosis and in two-thirds of patients with a more limited form of the disease known as CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasias). Progressive systemic sclerosis affects the skin in 90% of patients; the vascular system, esophagus, and intestines in 80%; the lungs in 45%; the heart in 40%; the kidneys in 35%; and the musculoskeletal system in 25% (1,2,7,12).

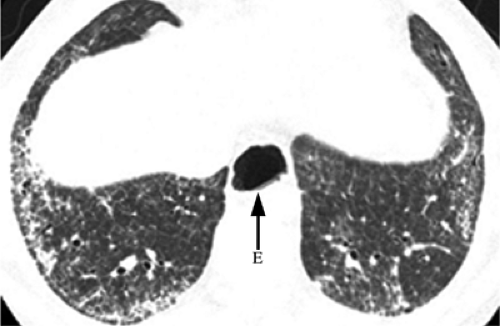

Basilar interstitial pneumonitis and fibrosis is the usual CXR abnormality, present in up to 80% (3) of patients with lung disease. The basilar distribution is even more pronounced in progressive systemic sclerosis than in other collagen vascular diseases. On CXR there may be fine or coarse reticulations at the bases with low lung volumes. HRCT demonstrates inter- and intralobular septal thickening, subpleural lines and micronodules, ground glass opacity, and honeycombing (Fig. 13.4). Aspiration pneumonia may occur secondary to disturbed esophageal motility. Esophageal dysmotility may result in a dilated air esophagram on CXR or CT. Pleural involvement is rare. Pulmonary arterial hypertension occurs in 6% to 60% (13), and sclerosis of cardiac muscle may result in cor pulmonale. There is an increased risk of lung cancer, especially bronchoalveolar carcinoma.

Basilar distribution of lung disease, typical of most collagen vascular diseases, is especially pronounced in scleroderma.

Polymyositis and Dermatomyositis

These diseases have an incidence of 1 to 8 per million, a bimodal age distribution with an early peak at 5 to 15 years and a later peak at 45 to 65 years, and male-to-female ratio of 1:4. There is an increased incidence of HLAs A1, B8, DR3, and DR5. Clinical presentation may be acute or chronic, with proximal muscle weakness, a heliotrope or violaceous skin rash in dermatomyositis, and telangiectasias over the joints of the hand. Dysphagia occurs in up to 50%. Skin and muscle changes may occur together or 2 to 3 months apart. General ill health and fever are common. Disease is associated with the anti-Jo1 antibody. In 10% there is an underlying malignancy, with carcinomas of lung, breast, stomach, and ovary being the most common. In men presenting over the age of 50, 60% have carcinoma, usually bronchogenic carcinoma (1,2,5). Polymyositis/dermatomyositis presents in one of four ways:

Primary idiopathic polymyositis/dermatomyositis;

Childhood polymyositis/dermatomyositis;

Polymyositis/dermatomyositis with neoplasia;

Polymyositis/dermatomyositis with collagen vascular disease.

In 10% of polymyositis patients there is an underlying malignancy, often in lung, breast, stomach, or ovary.

Figure 13.4 Scleroderma. High resolution computed tomography with interstitial abnormality limited to the lung bases. Note esophageal dilation (E). |

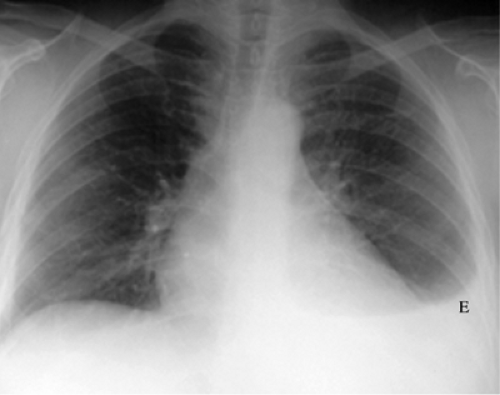

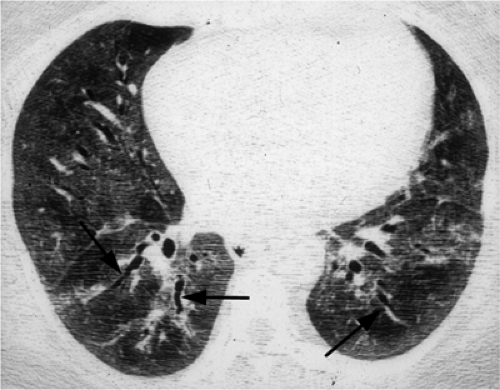

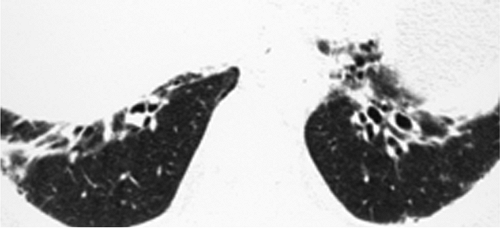

Chest radiographs are often normal. Basal interstitial pulmonary fibrosis indistinguishable from usual interstitial pneumonitis or nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis occurs in up to 10% (Figs. 13.5 and 13.6). Bronchiolitis obliterans and bronchiolitis obliterans

organizing pneumonia also occur. When pharyngeal muscle paralysis occurs in polymyositis, aspiration pneumonia may develop. Diaphragmatic elevation with small lung volumes can also be seen (3,7,14).

organizing pneumonia also occur. When pharyngeal muscle paralysis occurs in polymyositis, aspiration pneumonia may develop. Diaphragmatic elevation with small lung volumes can also be seen (3,7,14).

Figure 13.5 Dermatomyositis. High resolution computed tomography demonstrates extensive ground glass opacity with traction bronchiectasis (arrows). |

Figure 13.6 Dermatomyositis. High resolution computed tomography predominantly with traction bronchiectasis at the extreme lung bases. |

Ankylosing Spondylitis

Of all the seronegative arthritides, ankylosing spondylitis is the main one with chest manifestations. It has an incidence of 1 in 1,000, an age at onset of 15 to 35 years, and male-to-female ratio of 4:1. It is most common in people from the Indian subcontinent. It is more common in whites than blacks and is rare in East Asians. There is a 90% association with HLA B27 (1,2,5). Characteristic findings include synovitis, juxtaarticular osteitis and chondritis with erosion of subchondral bone, and skeletal ankylosis, especially of the sacroiliac joints. Calcification of paraspinal ligaments is noted if there is involvement of the lumbar, thoracic, or cervical spine. Aortic regurgitation is seen in up to 5% of patients. In 1% to 2% of patients, upper lobe pulmonary fibrosis and bullae develop. These fibrobullous lesions may contain mycetomas and are occasionally secondarily infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (3,7,15).

Unlike other collagen vascular diseases, lung disease in ankylosing spondylitis has an upper lobe predilection.

Pulmonary Vasculitides

The pulmonary vasculitides can be categorized according to the size of the vessels primarily involved (Table 13.3) and to whether they are associated with an elevated antinuclear cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA). These disorders have manifestations in many other organ systems, commonly the skin and kidneys, and frequently present with pulmonary hemorrhage (3).

Non–Antinuclear Cytoplasmic Antibody Associated Vasculitides

Large Vessel (Giant Cell) Vasculitis

Medium-sized Vessel Vasculitis

In polyarteritis nodosa, pulmonary artery involvement is rare, whereas bronchial artery involvement is common. However, thoracic radiologic findings are usually secondary to

cardiac and/or renal failure. A few cases of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia have been described (1,2,17).

cardiac and/or renal failure. A few cases of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia have been described (1,2,17).

Table 13.3: Principle Systemic Vasculitides | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Antinuclear Cytoplasmic Antibody Associated Vasculitides

Microscopic Polyangiitis

Microscopic polyangiitis is pauci-immune necrotizing small vessel angiitis without granulomatous inflammation. It is a rare disease, has a mean age at onset of 50 years, and a male-to-female ratio of 2:1. It presents with constitutional symptoms, including fever, arthralgias, myalgias, and purpura. pANCA is present in more than 80% of patients. It is the most common cause of a pulmonary–renal syndrome. Common radiologic findings in the chest are pulmonary edema in 6% of patients and pleural effusion in 15% (1,2,3,16).

Wegener Granulomatosis

Classic Wegener granulomatosis is a triad of (a) upper and lower respiratory tract necrotizing granulomatous inflammation, (b) systemic small vessel vasculitis, and (c) necrotizing glomerulonephritis. It has an incidence of 3 per million, a mean age at onset of 40 years, and a male-to-female ratio of 1.3:1. There is an increased incidence of HLAs B8 and DR2. Onset is usually acute or subacute but may be indolent. In patients with Wegener granulomatosis, 85% have a positive cANCA (1,2,3).

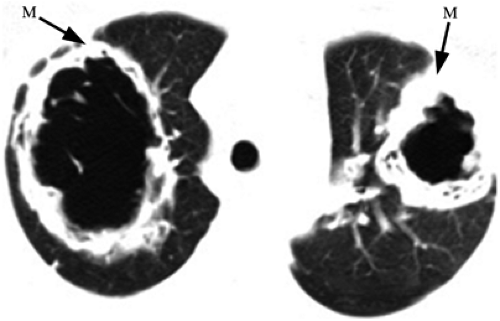

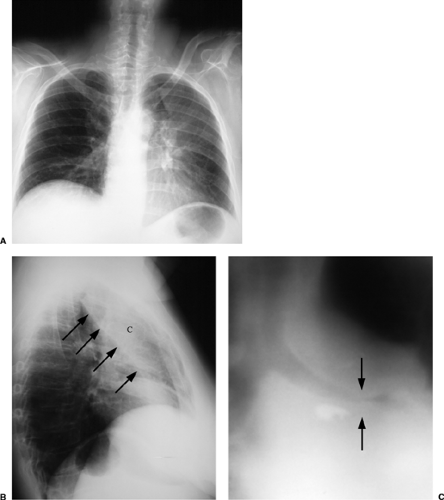

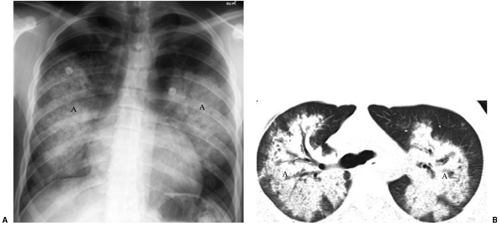

The upper respiratory tract is involved in 100% of cases, affecting the nasal cavity with cartilage destruction and the sinuses with mucosal thickening. Pulmonary involvement is present in 85% to 90% (5). The classic CXR shows widely distributed multiple irregular nodules or masses, varying up to 9 cm, mainly in the lower lungs. Nodules cavitate in 25% to 50% of patients (Fig. 13.7) and are sometimes single. Patchy airspace disease due to pneumonia or pulmonary hemorrhage also occurs (Fig. 13.8). Pleural effusions occur in

25% and tracheobronchial stenosis is not uncommon (Fig. 13.9), but lymph node enlargement is rare. Limited Wegener granulomatosis is Wegener granulomatosis without the renal involvement (3,16,17,18).

25% and tracheobronchial stenosis is not uncommon (Fig. 13.9), but lymph node enlargement is rare. Limited Wegener granulomatosis is Wegener granulomatosis without the renal involvement (3,16,17,18).

Common thoracic manifestations of Wegener granulomatosis are lung nodules or cavities, pulmonary hemorrhage, pleural effusions, and tracheobronchial stenosis.

Churg-Strauss Syndrome

This consists of a triad of (a) allergic rhinitis and asthma, (b) eosinophilic pneumonia and gastroenteritis, and (c) systemic small vessel vasculitis with granulomatous inflammation. The disease often evolves in this order. It is rare, has a typical age at onset of 38 to 57 years, and affects men and women equally. pANCA is elevated in 70%, cANCA is rarely elevated, tissue eosinophilia occurs in 100% with serum eosinophilia in greater than 30%, and serum IgE is commonly elevated. The cardiac, gastrointestinal, skin, and central nervous systems are commonly involved (1,2,3,5). CXR manifestations include patchy airspace disease, noncavitary pulmonary nodules, and pleural effusions. Cardiopericardial silhouette enlargement results from pericarditis and/or myocarditis (16,17,19).

Figure 13.8 Wegener granulomatosis. A. Chest x-ray and (B) computed tomography: pulmonary hemorrhage manifesting as bilateral central airspace disease (A). |

Immune-Complex Vasculitis

Necrotizing Sarcoidal Angiitis

Necrotizing sarcoidal angiitis is distinguished from sarcoidosis by the presence of arteritis. It is a rare disorder, has a mean age at onset of 45 years, and a male-to-female ratio of 1:2.5. In general, this is a benign condition that does not require treatment (1,2,3). Radiologically, the most common pattern is bilateral nodules, occurring in 75% of patients and ranging up to 4 cm in diameter. There is a slight predilection for the lower lobes. Nodules may cavitate and may be miliary. Less common patterns include bilateral airspace disease, basal interstitial abnormality, and pleural effusions (16).

Diffuse Pulmonary (Alveolar) Hemorrhage

Table 13.4 lists the causes of diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage (3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree