Other Thoracic Neoplasms

This chapter covers a variety of benign and malignant thoracic neoplasms, arising with the airway, lung parenchyma, esophagus, and the lymphatic system, as well as metastases to the thorax. Lung cancer was discussed in Chapter 7, pleural neoplasms are discussed in Chapter 17, and the rare tumors of the vascular system are discussed briefly in Chapters 18, 20, and 21. A full discussion of all these neoplasms could easily be the topic of an entire text unto itself. What you will read here is a discussion of the more common of these entities and, when possible, specific imaging features that can be helpful in distinguishing one from another.

Tracheobronchial Neoplasms

Benign and malignant tracheobronchial neoplasms are rare and vary widely histologically. When they occur in the trachea, they may present with a nonproductive cough due to irritation, hemoptysis if they bleed, or wheezing and/or dyspnea due to airway obstruction. When they occur in the bronchi, they may also cause postobstructive pulmonary infection. Recurrent infection, especially within the same lobe or segment, is suggestive of an endobronchial lesion.

Tracheobronchial neoplasms often present with stridor and wheezing.

On chest radiographs, lobar or segmental airspace disease, obstructive pneumonitis, or atelectasis may be seen. Abscess or bronchiectasis may also develop when the obstruction is longstanding. Endobronchial lesions may create a ball–valve phenomenon, with an open airway at inspiration and a closed airway in early expiration, creating hyperinflation and obstructive emphysema distal to the occlusion. Although sometimes visible on an inspiratory radiograph, this phenomenon is best recognized on expiratory or ipsilateral decubitus radiographs. The tumor itself is uncommonly identified on the chest radiograph; however, the tumor, extent of tumor spread, and associated findings are readily identified on computed tomography (CT). Characteristically, the recognition of malignant lesions is based on the following triad:

Abnormal or obstructed airways;

A central mass, causing distinct bulging of the proximal contour of the collapsed lobe or segment;

Differential enhancement of tumor versus collapsed peripheral lung after administration of intravenous contrast (1).

CT with multiplanar reconstructions is the preferred imaging modality for evaluating airway lesions (Chapter 16). Inspiratory and expiratory CT examinations are usually performed to evaluate the impact of the lesion on the airway during the respiratory cycle. Intravenous contrast is usually administered for better evaluation of the neoplasm with

respect to adjacent mediastinal structures, particularly when there is extension outside the airway (2,3,4). Many of the benign and malignant tracheobronchial neoplasms can also arise within the small bronchi of lung parenchyma, and some tumors of the same cell type may arise from pleura, as can be seen from the overlap in Tables 8.1 to 8.4.

respect to adjacent mediastinal structures, particularly when there is extension outside the airway (2,3,4). Many of the benign and malignant tracheobronchial neoplasms can also arise within the small bronchi of lung parenchyma, and some tumors of the same cell type may arise from pleura, as can be seen from the overlap in Tables 8.1 to 8.4.

Table 8.1: Benign Tracheobronchial Neoplasms | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Table 8.2: Benign Pulmonary Neoplasms | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Table 8.3: Malignant Tracheobronchial Neoplasms | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Table 8.4: Malignant Pulmonary Neoplasms | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Benign Tracheobronchial Neoplasms

Papilloma

Squamous papillomas are the most common laryngeal tumor in childhood. In 2% to 17% of patients they involve the tracheobronchial tree (Fig. 16.17). More rarely they involve the lung parenchyma. Lesions may be single or multiple, and the laryngeal disease may be present for up to 10 years before tracheobronchial disease occurs. Malignant transformation has been described and is extremely rare. Papillomas are much rarer in adults than children, usually presenting between the ages of 50 and 70 years. In adults, laryngeal papillomatosis is usually absent. As of 1991 only 59 adult cases were documented in the literature (3,5).

Squamous cell papilloma is the most common laryngeal tumor in children.

The chest radiograph and CT findings of papilloma include pneumonia, bronchiectasis or abscess formation secondary to obstruction. When the lungs are involved, multiple, small, well-defined, scattered pulmonary nodules are found, which may cavitate.

Lipoma

This is a benign tumor of adipose tissue or lipocytes. It has a mean age at onset in the fifth decade. They are more common in smokers than nonsmokers and more common in males than females, with a ratio of 5:1. Approximately 80% of lesions arise in the tracheobronchial tree and 20% within the lung parenchyma; 109 cases have been reported. Lesions are usually solitary, may be pedunculated, and have been reported up to 3 cm in size. Lipomas can also arise from the pleura (Fig. 17.25). Radiologically, findings are related to airway obstruction or the mass itself. On CT they demonstrate characteristic homogeneous fat attenuation. Liposarcoma is the malignant equivalent. It is very rare, with less than 10 cases reported. It usually occurs in the lung parenchyma and occurs equally in men and women. At CT, liposarcoma should be suspected when the fat attenuation mass also contains areas of soft tissue nodularity (5,6,7).

Fibroma

Fibromas occur equally in males and females. They arise from within the bronchial wall, but may also arise within the lung parenchyma. They may grow to be very large. The endobronchial lesions may cause lobar or segmental atelectasis due to obstruction. They may also present as a solitary pulmonary nodule, often incidentally detected in asymptomatic individuals. Fibrosarcoma is the malignant equivalent of fibroma. Similarly, lesions may be endobronchial or lung parenchymal in location. The mean age at onset is 49 years. At CT, both fibroma and fibrosarcoma appear as soft tissue masses; the latter may have features of invasion and spread outside the airway, into or around other mediastinal structures (8,9).

Chondroma

Chondromas usually arise from the cartilage in the walls of large bronchi and are usually 1 to 2 cm in size. When multiple, they should raise suspicion of Carney syndrome, a triad of bronchial chondroma, gastric leiomyoma, and extraadrenal functional paragangliomas. Less commonly, chondromas arise within the lung parenchyma and appear as a solitary pulmonary nodule, usually detected incidentally in asymptomatic individuals. The malignant equivalent is a chondrosarcoma. It is very rare. It occurs equally within the endobronchial tree and lung parenchyma, is slightly more common in women, and has a mean age at onset of 55 years. Like fibromas, the radiologic and clinical features depend on the presence or absence of airway obstruction. In addition to a soft tissue mass, they may also contain areas of calcification (5,7,9).

Carney syndrome: bronchial chondromas, gastric leiomyoma, and extraadrenal paragangliomas.

Granular Cell Tumor (Myoblastoma)

Granular cell tumors, otherwise known as myoblastomas, may arise within the skin, breast, tongue, or esophagus. Approximately 6% are endobronchial in location, of which approximately 100 cases have been reported. They appear as either polypoid or sessile soft tissue masses in the large bronchi or in the trachea near the carina, ranging in size from 5 to 60 mm (Fig. 8.1). Rarely, they arise in the lung parenchyma. The imaging features are similar to fibroma (5,9,10).

Malignant Tracheobronchial Neoplasms

The most common epithelial neoplasms are bronchogenic carcinomas (Chapter 7). Carcinoid tumors and bronchial gland tumors are discussed here. The most common malignant neoplasms of the trachea are squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. CT is the preferred imaging modality for evaluation of malignant tracheal neoplasms.

Carcinoid

Carcinoid tumors represent 5% of pulmonary tumors and are usually seen in either young adults when benign or in adults older than 50 years when more aggressive. Low and intermediate grade tumors occur equally in males and females, whereas the high grade tumors are two to four times more common in men. Carcinoid tumors are also up to 25 times more common in Caucasians than in African Americans. Carcinoid tumors are a spectrum of benign, invasive, and malignant lesions, representing a histopathologic spectrum of neuroendocrine neoplasms that originate from neurosecretory cells (Kulchitsky cells) of the bronchial mucosa. These slow-growing malignant neuroendocrine tumors are part of the amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation system and may secrete a number of hormones, including calcitonin, bradykinin, norepinephrine, antidiuretic hormone, and adrenocorticotrophic hormone. Histologically, they are divided into three groups (Table 8.5).

Carcinoid tumors are neuroendocrine in origin and are on a histopathologic spectrum that ranges from benign carcinoids to small cell carcinoma.

Approximately 80% of carcinoid tumors are endobronchial in location, and the remaining 20% arise in the lung parenchyma as a solitary pulmonary nodule. The latter arise from small bronchi, a feature seen at pathologic examination but usually not recognizable with imaging. Given the histopathologic spectrum, the clinical presentation and radiologic findings are variable, ranging from locally confined and usually low grade tumors to locally invasive tumors. The intermediate and high grade tumors have a tendency to recur and metastasize to extrathoracic sites; the incidence of metastases depends on tumor grade (11,12,13,14).

Classic carcinoid is the least aggressive and has a mean age at onset of 50 years. These tumors are usually centrally located in the airway and are less than 2.5 cm in size. They infrequently metastasize to lymph nodes and have a good prognosis. They occur more frequently in the right middle lobe than other lobes of the lung and have a 5-year survival of 87%. Atypical carcinoid tumors are usually greater than 2.5 cm in size, with a mean age at onset of 57 years. Although they have well-defined margins, lymph node metastases occur in 50% of patients and other organ metastases in 30% of patients. The prognosis is therefore less favorable, with a 5-year survival rate of 56% (12,13,14).

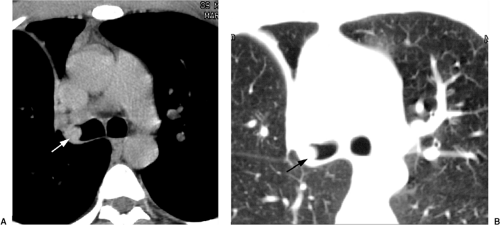

Small cell carcinoma has a mean age at onset of 62 years and is twice as common in males than females. It is the most aggressive form of carcinoid tumor and has the worst prognosis. It is usually an ill-defined lesion (Fig. 8.2), with extensive mediastinal lymph node involvement at the time of diagnosis. Similarly, large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma has a mean age at onset of 62 years and is four times more common in males than females. The 27% 5-year survival of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma is better than the 9% 5-year survival for small cell carcinoma; however, the 10-year survival rate for both is poor, at just over 5% (12,13,14).

With carcinoid tumors, 90% of the chest radiographs are abnormal. Abnormalities include lobar or segmental atelectasis or hyperinflation, obstructive pneumonitis, bronchiectasis or lung abscess. They can also appear as a solitary nodule (Figs. 8.2 and 8.3)

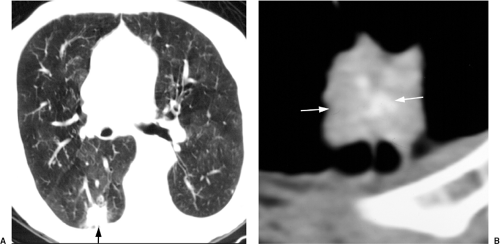

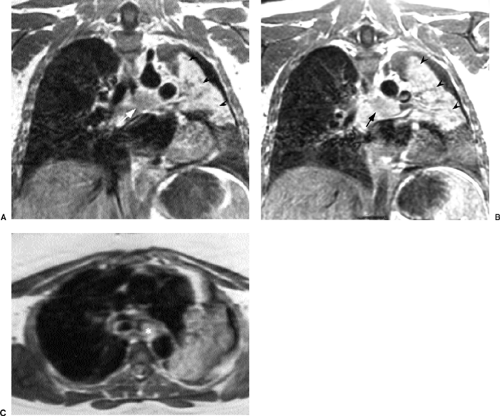

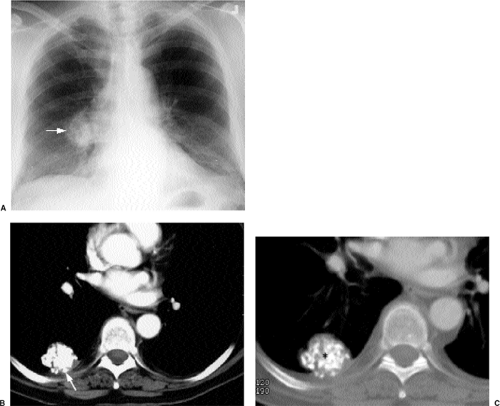

or as a pedunculated mass. Occasionally, they contain areas of apparent calcification (Fig. 8.4), which represents ossification histologically. CT is excellent at demonstrating both the intraluminal and extraluminal component of these tumors. Up to 25% of classic and atypical carcinoid tumors have calcification on CT. Intravenous contrast enhancement of the lesions is classically intense (Fig. 8.5), not surprising given what is often referred to at bronchoscopy as a “cherry red” lesion that commonly has visible vessels on its surface. Carcinoid tumors can also be demonstrated with radiolabeled octreotide scans or with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 8.6) due to high signal from the tumor and the low background signal from normal lung and flowing blood (2,15).

or as a pedunculated mass. Occasionally, they contain areas of apparent calcification (Fig. 8.4), which represents ossification histologically. CT is excellent at demonstrating both the intraluminal and extraluminal component of these tumors. Up to 25% of classic and atypical carcinoid tumors have calcification on CT. Intravenous contrast enhancement of the lesions is classically intense (Fig. 8.5), not surprising given what is often referred to at bronchoscopy as a “cherry red” lesion that commonly has visible vessels on its surface. Carcinoid tumors can also be demonstrated with radiolabeled octreotide scans or with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 8.6) due to high signal from the tumor and the low background signal from normal lung and flowing blood (2,15).

Table 8.5: Histopathologic Spectrum of Carcinoid Tumors | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

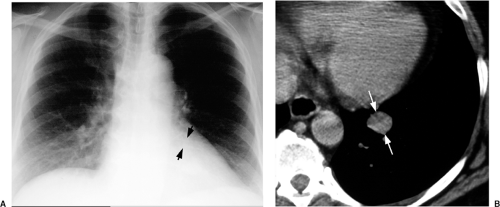

Figure 8.2 Limited stage small cell carcinoma presenting as a left upper lobe solitary pulmonary nodule on computed tomography. |

Figure 8.3 Carcinoid tumor. A. Chest radiograph and (B) computed tomography demonstrate a left lower lobe solitary pulmonary nodule of soft tissue attenuation (arrows). |

Figure 8.5 Carcinoid tumor. Computed tomography with intravenous contrast. Carcinoids are vascular tumors. The tumor (left asterisk) and aorta (right asterisk) have similar enhancement. |

Bronchial Gland Carcinomas

Bronchial gland tumors include adenoid cystic carcinoma, also known as cylindroma, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma. The term “bronchial adenoma” was used in the past to include these tumors as well as carcinoid tumor. Inclusion of the latter group is incorrect, because they have a different cell of origin.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma arises from mixed serous and mucinous glands located in the posterolateral wall of the trachea and major bronchi. They occur in middle age, are more aggressive than carcinoid tumors, and have a greater propensity for both local invasion and metastases. They usually arise in the lower trachea, main or lobar bronchi. Chest radiograph abnormalities are usually due to chronic bronchial obstruction and may be present for a number of years before diagnosis. Adenoid cystic carcinoma has a tendency to grow along the length of the airway in a submucosal manner, so that the length of the airway involved is usually greater than is appreciated with CT examination (Fig. 16.20). The length of the airways excised is usually greater that what is visible with imaging. The tumor can locally recur, often many years after initial resection. In a series from the Mayo Clinic, 55% of patients were alive at 10 years (13,16).

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma is a mixture of mucous-secreting, squamous, and intermediate cells. It usually affects the trachea as a locally invasive sessile or polypoid tumor. It is rare. Half of patients are less than 30 years of age. Low-grade tumors rarely are locally invasive or metastasize; local resection (such as sleeve resection) has an excellent prognosis. High grade lesions are treated with surgery and postsurgical radiotherapy (13,16).

Benign Pulmonary Neoplasms

There is a wide spectrum of benign pulmonary neoplasms that may arise from the many cellular elements present in the lung. In general, they appear on imaging as indeterminate solitary pulmonary nodules. The most common are the pulmonary hamartomas, and they are discussed first. Where possible, specific imaging findings that can lead one to a specific diagnosis are indicated. Others neoplasms that also occur within the tracheobronchial tree have already been discussed.

Hamartoma

Hamartomas are an abnormal quantity, mixture, or arrangement of the normal constituents of the organ in which they are found. They usually occur in patients between 40 and 70 years of age and are two to four times more common in males than females. Most

arise within the lung periphery; however, 10% to 20% have an endobronchial origin. Rarely, they may be multiple.

arise within the lung periphery; however, 10% to 20% have an endobronchial origin. Rarely, they may be multiple.

A hamartoma represents an abnormal quantity of cellular elements normally present in the organ in which they are found.

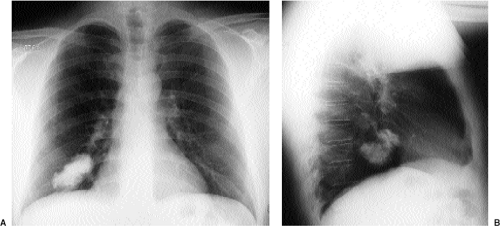

Figure 8.7 Hamartoma. Posteroanterior (A) and lateral (B) chest radiographs demonstrate a right lower lobe lobulated calcified mass. |

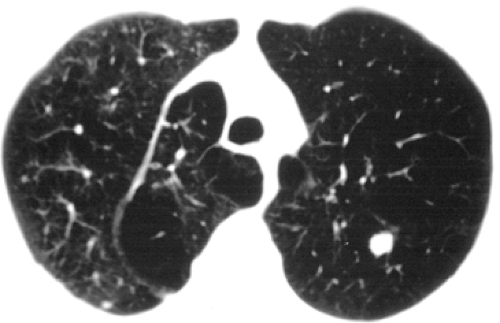

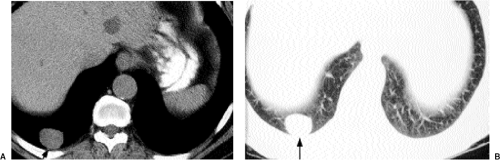

On chest radiograph or CT lesions are seen as well-defined round or ovoid nodules that can be lobulated or notched (Fig. 8.7). They are usually 2 to 5 cm in diameter, with most less than 4 cm in diameter. Calcification is common, being more common the larger the diameter of the hamartoma (Figs. 8.7 and 8.8). On chest radiography and CT, hamartomas are most commonly seen as homogeneously soft tissue opacity and attenuation, respectively (Fig. 8.9). At chest radiography or CT, the presence of “popcorn calcification” is classic and nearly pathognomonic (Fig. 8.10). Fat attenuation with the nodule on CT is demonstrated in approximately one-third of hamartomas and is pathognomonic (Fig. 8.8).

Cavitation is extremely rare. At MRI, hamartomas have intermediate signal on T1-weighted images and high signal on T2-weighted images. Septa may be demonstrated dividing the lesion into lobules within the nodule, and these septa may enhance intensely after intravenous gadolinium. Endobronchial lesions cause radiologic signs of obstruction (5,17).

Cavitation is extremely rare. At MRI, hamartomas have intermediate signal on T1-weighted images and high signal on T2-weighted images. Septa may be demonstrated dividing the lesion into lobules within the nodule, and these septa may enhance intensely after intravenous gadolinium. Endobronchial lesions cause radiologic signs of obstruction (5,17).

Figure 8.8 Calcified hamartoma. Computed tomography demonstrates a hamartoma within the lingula (arrow) with central calcifications (arrowhead) and adjacent low attenuation representing fat. |

Figure 8.9 Hamartoma. Computed tomography at (A) soft tissue window settings and (B) lung window settings demonstrates a solitary right lower lobe lung nodule of soft tissue attenuation (arrow). |

Figure 8.10 Calcified hamartoma on (A) chest radiograph and (B) computed tomography. Soft tissue settings demonstrates a lobulated and calcified right lower lobe mass (arrow). Computed tomography on bone window settings (C) more clearly demonstrates the morphology of the internal calcification (asterisk).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|