Fig. 19.1

Oesophagram demonstrating a 5 cm Zenker’s diverticulum

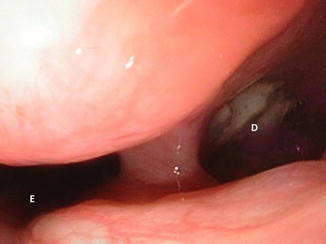

Fig. 19.2

Endoscopic appearance of Zenker’s diverticulum. Key: E oesophageal lumen, D diverticulum

The cervical oesophagus and diverticulum are approached as described. The diverticulum is located posterior to the cricoid cartilage and is enclosed in loose areolar tissue. The diverticulum must be carefully dissected away from the tissue to expose its base. A myotomy is then performed from the base of the neck of the diverticulum and extending inferiorly through the cricopharyngeal muscle and extending for 5–7 cm along the posterolateral cervical oesophagus. The cricopharyngeal muscle is typically thick and fibrotic and must be completely divided to ensure success of the operation. The oesophageal mucosa must be carefully dissected away from the muscle being divided to ensure that perforation does not occur. The myotomy should not be extended proximally into the inferior pharyngeal constrictors to avoid impairing pharyngeal contractions.

Once the myotomy has been performed, the diverticulum is addressed. Diverticula less than 2 cm in size will often resolve on their own and do not need to be addressed. Larger diverticula can be suspended by tacking the apex of the diverticulum superiorly to the prevertebral fascia. Diverticula greater than 5 cm cannot be adequately suspended and should be resected. These can be excised using a stapling device with a bougie in place to avoid luminal compromise (52–58 Fr depending on oesophageal lumen size). Prior to closure, the myotomy and diverticular staple line (if performed) can be assessed by using an endoscope to insufflate air into the cervical oesophagus. Alternatively, a nasogastric tube passed into the oesophagus can be used to insufflate air. The endoscope has the added advantage of allowing evaluation of the diverticular neck to ensure that it has been adequately obliterated from suspension as well as ease of entry into the cervical oesophagus. The neck is closed after ensuring haemostasis. A closed suction drain is placed by some prior to closure.

If a small mucosal perforation was inadvertently performed, it can be closed primarily and a drain placed. Before neck closure, it is critical to ensure perfect haemostasis because a haematoma requiring re-exploration can develop from even small vessels secondary to coughing or straining as the patient awakens from anaesthesia.

Postoperative complications are rare and include oesophageal leak from mucosal injury, neck haematoma and recurrent nerve injury. Mucosal injuries resulting in a leak present, like other oesophageal perforations, with fever, neck pain, elevated white blood cell count and crepitus. Small perforations can be managed conservatively by restricting oral intake and antibiotics. Larger perforations require exploration, repair and drainage. Large haematomas require prompt drainage. Recurrent nerve injury can occur with any cervical oesophageal surgery and has been already addressed [27, 28].

Zenker’s diverticulum can also be approached endoscopically [20–22, 29]. In this approach, a common channel is created between the diverticulum and the upper oesophagus by division of the cricopharyngeal muscle. A stapling device is used to create the common channel. It is essential that the entire cricopharyngeal muscle be divided to ensure a complete myotomy such that symptoms are resolved. Various techniques have been described including placing sutures in the muscle endoscopically so as to lift the muscle into the stapling device. Oesophageal perforation can also occur with this method and treated as described previously.

19.5 Cervical Oesophageal Trauma and Drainage of Retropharyngeal Abscess

Cervical oesophageal trauma can result from numerous aetiologies, including iatrogenic injuries from endoscopic instrumentation, penetrating or blunt trauma or caustic or foreign body ingestion [30–32]. The cervical portion is the most common site of iatrogenic injury during instrumentation (50–70 % in most modern series) [30, 33–37]. Although rare, oesophageal perforation also can result from nasogastric tube placement, oesophageal intubation with an endotracheal tube and surgical procedures performed in proximity to the cervical oesophagus, such as tracheostomy, thyroidectomy and various spinal procedures.

Penetrating trauma to the neck can obviously lead to injury. Owing to the oesophagus’ proximity to critical structures such as the carotid artery and trachea, other life-threatening injuries to these adjacent structures must often be addressed first. Blunt injury to the oesophagus is also possible but rarely leads to through-and-through perforations. Most commonly, direct blows to the neck lead to intramucosal oesophageal haematoma and consequent dysphagia. These haematomas resolve with conservative management [30, 33].

The severity of caustic oesophageal injury often as a result of a suicide attempt depends on the type, quantity and duration of the chemical ingested. Alkaline exposure (e.g. lye) causes a liquefactive necrosis which is more severe than the coagulative necrosis caused by acid (e.g. battery acid or bleach) [32–34]. Full-thickness oesophageal injuries of the cervical oesophagus from caustic ingestion signify significant exposure with resultant injury to the oropharynx, the thoracic and abdominal oesophagus as well as the stomach.

Regardless of its aetiology, oesophageal trauma leading to oesophageal perforation is a medical emergency and requires prompt attention. Delays in diagnosis and subsequent treatment lead to increased patient morbidity and mortality.

The clinical manifestations of cervical oesophageal perforation include tachycardia, fever, neck pain, subcutaneous air, pain, dysphagia as well as subjective shortness of breath. The need for diagnostic studies depends on the clinical scenario and degree of suspicion for oesophageal injury. In cases of iatrogenic injury during endoscopy, no further studies are needed as the injury is directly visualized. Otherwise, an oesophagram or neck CT scan with oral contrast material can confirm the diagnosis in over 90 % of patients (Fig. 19.3). Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy is used after the injury has been diagnosed by radiographic studies to localize the site of injury in the operating room [30, 35].

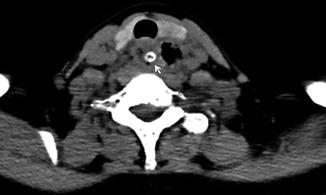

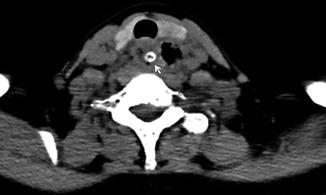

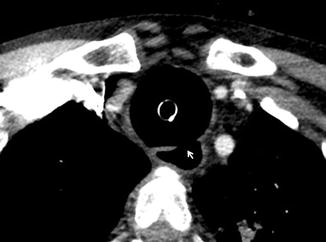

Fig. 19.3

Neck CT appearance of cervical oesophageal perforation due to a foreign body (arrow) with extensive subcutaneous emphysema in the neck

Cervical oesophageal perforations are typically contained by the deep cervical fascia with less tissue contamination. Hence, mortality rates after cervical oesophageal perforation are low especially when the contamination has not spread to the mediastinum [30, 31, 33, 35–39].

Surgical treatment for cervical oesophageal perforation is required when there is widespread soilage from a large full-thickness injury. The main principles of surgical intervention require controlling the perforation and draining the area of contamination.

Primary repair of cervical oesophageal perforation is possible. Cervical oesophageal injuries can often be repaired primarily when the contamination is minimal. The oesophagus is mobilized as described before and the area of perforation identified. If the site of perforation is not evident, endoscopy can be used to identify the location. When the site is identified, its full extent should be evaluated by opening the muscle layers over the perforation. A two-layer repair is recommended, with reapproximation of the mucosa and closure of the muscularis propria. The repair then is reinforced with viable tissues such as the strap muscle or a partial sternocleidomastoid muscle flap [30, 33, 39]. The neck wound is thoroughly irrigated and extensively drained or left open and packed. In cases where repair is not possible, devitalized tissue should be debrided, the wound irrigated and the wound packed open. The resulting oesophagocutaneous fistula will heal over time. Breakdowns of a primary repair would be treated in a similar fashion. The patient in this situation would require total parenteral nutrition (TPN) or preferably a feeding tube for alimentation until the fistula healed.

Late complications from repairs or drainage of oesophageal injury include tracheo-oesophageal fistula, strictures and abscess formation. Strictures can be treated with serial dilations or occasionally stenting, but severe caustic strictures often require oesophagectomy and reconstruction. Tracheo-oesophageal fistula also requires operative intervention as outlined in the subsequent section. A postoperative retropharyngeal abscess would be drained similarly to a primary abscess caused by infection spreading from the nasopharynx, tonsils, middle ear and sinuses or occasionally by upper respiratory infection. The retropharyngeal space would be approached as for exposing the cervical oesophagus. The oesophagus would then be rotated medially to expose the prevertebral fascia and the retropharyngeal space. Care should be taken to not damage surrounding tissue which may be inflamed from the infection. The abscess would be evacuated and the wound packed and closed by secondary intention over the course of time.

19.6 Benign Tracheo-Oesophageal Fistula

Acquired tracheo-oesophageal fistula can be benign or malignant in origin. Malignant fistulas are typically caused by inoperable oesophageal cancer. Patients with malignant fistulas are palliated with airway or oesophageal stents. The benign acquired tracheo-oesophageal fistulas are typically the result of airway and oesophageal trauma such as from prolonged intubation with a nasogastric tube in place or postoperative complications after cervical neck procedures [17, 18, 40–44]. Regardless of its aetiology, acquired tracheo-oesophageal complication is a serious potentially life-threatening condition. By bypassing the normal protective reflexes of the upper pharynx, the airways are exposed to persistent soilage, leading to recurrent pneumonias, sepsis and death. Tracheo-oesophageal fistulas also create challenges for patients requiring positive pressure ventilation as there can be significant tidal volume loss from the fistula.

A variety of non-malignant conditions can lead to acquired tracheo-oesophageal fistulas and include blunt or penetrating trauma, granulomatous infection from tuberculosis, prior tracheal or oesophageal surgery, complications of caustic ingestion of corrosive fluids or foreign body ingestion (small disc batteries) [17, 18, 40–45]. They can also result from direct iatrogenic injury from endoscopic and bronchoscopic procedures such as stenting, intubation, trans-oesophageal echocardiography or percutaneous tracheostomy.

Endotracheal or tracheostomy cuff-related trauma occurs in 75 % of the cases of acquired benign tracheo-oesophageal fistula formation [17, 42]. Prolonged ventilation with an endotracheal tube or tracheostomy can result in ischaemia and consequent tissue necrosis of the posterior membranous tracheal wall and the anterior trachea, leading to fistula formation. This process is expedited if the balloon cuff of the endotracheal tube or tracheostomy tube is overinflated or nasogastric tube is present in the oesophagus providing a noncompliant posterior surface for the balloon.

An acquired tracheo-oesophageal fistula typically presents in ventilated patients with recurrent pulmonary infections and failure to wean from the ventilator. They should be considered in these patients and all ventilated patients with unexplained tidal volume loss or gastric dilatation. In non-ventilated patients, symptoms include repeated pulmonary infections and aspiration-like systems with swallowing of liquids. Diagnosis is best made by endoscopy or bronchoscopy when a tracheo-oesophageal fistula is suspected. Other radiographic modalities, including chest CT (Fig. 19.4) and oesophagram, can also make the diagnosis. Radiographic diagnosis is often incidental as the study is ordered for other reasons.

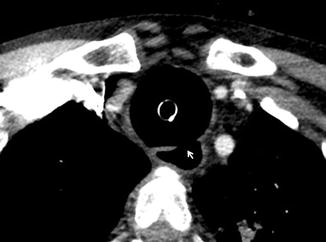

Fig. 19.4

Neck CT demonstrating tracheo-oesophageal fistula (arrow)

Surgical treatment is the mainstay of treatment for patients who are operative candidates. Those with excessive co-morbid conditions can be palliated with a stent and reconsidered for a definitive procedure if their condition improves. The placement of an airway or oesophageal stent would be weighed carefully as it may increase the size of the fistula and make subsequent surgery prohibitive.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree