Theresa Gramlich

Long-Term Ventilation

Learning Objectives

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

1 State the goals of mechanical ventilation in a home environment.

2 List the criteria for selection of patients suitable for successful homecare ventilation.

3 Name the factors used to estimate the cost of home mechanical ventilation.

5 Identify the factors used when considering selection of a ventilator for home use.

8 List follow-up assessment techniques used with home-ventilated patients.

9 Describe some of the difficulties families experience when caring for a patient in the home.

12 Name the appropriate modes used with first-generation portable/homecare ventilators.

15 List the items that should appear in a monthly report of patients on home mechanical ventilation.

18 Recognize from a clinical example a potential complication of negative-pressure ventilation.

19 Name three methods of improving secretion clearance besides suctioning.

21 List five psychological problems that can occur in ventilator-assisted individuals.

22 Explain the procedure for accomplishing speech in ventilator-assisted individuals.

23 Compare the functions of the Portex and the Pittsburg speaking tracheostomy tubes.

25 List six circumstances in which speaking devices may be contraindicated.

Key Terms

• Chest cuirass

• Decannulation

• Erosive esophagitis

• Gastrostomy or jejunostomy tubes

• Ileus

• Pneumobelt

• Respite care

• Rocking bed

Most patients receiving mechanical ventilation require ventilatory support for less than 7 days. Approximately 5% of those patients requiring more than 7 days cannot be successfully weaned from ventilatory support and remain chronically ventilator dependent after 4 weeks.1 For these patients, weaning is slow paced and may not always end in success.2

Long-term mechanical ventilation (LTMV) is required by two categories of patients: those recovering from an acute illness and those with chronic progressive disorders. Patients who have an acute, severe illness may not recover sufficiently to be weaned from ventilation while in an acute-care facility. After the acute illness has resolved, these patients are generally transferred to special units on mechanical ventilation within the hospital, long-term care facilities, or their homes. Obstructive diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and restrictive diseases, such as kyphoscoliosis, are essentially incurable, and the disease process is usually progressive. Patients with these disorders often become compromised with chronic respiratory failure requiring LTMV.3

Mortality rates for patients receiving LTMV are high (2-year mortality rate of 57%; 5-year mortality rate range of 66%-97%).4,5 Patients who are successfully liberated from the ventilator and decannulated have the best chance of survival.4

The number of ventilator-assisted individuals (VAIs) being discharged to homes or alternate care sites has increased over the past 2 decades (Key Point 21-1).6 Approximately 11,419 VAIs were in the United States in 2002, with care requiring an annual cost of almost $3.2 billion. Most of the cost for VAIs is absorbed by acute-care hospitals, where reimbursement is often inadequate. As a consequence of rising costs and falling reimbursements, specialized respiratory care units in acute, intermediate, and chronic-care facilities were developed. However, recent growth of these specialty units has slowed, again because of limited funding and reimbursement.3,7

Five major factors have added to this upsurge in numbers of VAIs during the past 2 decades:

1 First, continued advances in pulmonary medicine and technology have contributed to increased survival rates of critically ill adults and children. Many of these patients can be saved, stabilized, and sent home or to alternative sites for continued ventilator support.8

4 Fourth, simpler and more versatile equipment is available for home use.

An excellent example of a VAI who not only survived but lived a quality life is Christopher Reeve, an actor and active sportsman who sustained a high cervical fracture as a result of a horseback riding accident that left him a quadriplegic. With his determination and the support of his wife, family, and caregivers, he was able to have a productive life while being maintained on LTMV for 10 years. During this time, he directed films, became a public speaker, and raised awareness of spinal cord injury. He also strongly supported stem cell research.9

As baby boomers age, the number of older Americans is increasing, along with an increase in the number of people with chronic illnesses. Given these trends and the demand for more stringent methods of controlling health care costs, the number of VAIs discharged to home or alternate care sites will continue to increase. LTMV has been shown to be safe and effective alternative to acute-care institutionalization. The home is generally the least expensive environment and the one that provides the greatest level of patient independence and family support. A large part of this chapter is devoted to a discussion of home mechanical ventilation.

Goals of Long-Term Mechanical Ventilation

The overall goal of LTMV at home or other alternative care sites is to improve the patient’s quality of life by providing the following environmental attributes1,10:

• Enhancing the individual’s living potential

• Improving physical and physiological level of function

Because patients require different levels of care, it is desirable for every patient to progress to their point of maximum activity and take an active role in their own care. If this is accomplished, then their psychosocial well-being will also improve.

Sites for Ventilator-Dependent Patients

The terminology used to describe facilities for VAIs is not standardized. Sites can be grouped in three general categories: acute care, intermediate care, and long-term care.1

Acute-Care Sites

Acute-care sites include the following:

• Specialized respiratory care units, which have fewer resources and are generally designed for more stable VAIs. These are often designated units within a hospital and may be called pulmonary specialty wards,6 respiratory special care units,11 and chronic assisted ventilator care units.12

• Long-term acute-care hospitals, which are specifically designed to care for patients who require extensive monitoring and care, such as daily physician visits, continuous monitoring, intravenous therapy, wound care, and isolation. These patients may still be acutely ill but no longer require the intensive care provided in a critical care unit in the hospital.12 Long-term ventilator hospitals fall in this category.

Studies of VAIs in specialized units located within a hospital found that, compared with a control group, had the following characteristics:

• Lower hospital mortality rates

• Higher likelihood of being discharged to their homes

• Longer life expectancy after discharge

Success revolved around the strong leaderships of pulmonologists, who were dedicated to the care of these individuals.13

Intermediate-Care Sites

Intermediate-care sites usually include subacute care units, long-term care hospitals, and rehabilitation hospitals. Intermediate-care sites are not as expensive as acute-care sites and provide somewhat more patient independence and quality of life.

Subacute care units may be located in acute care hospitals. They often admit patients who require physiological monitoring, intravenous therapy, or postoperative care.

Long-term care hospitals provide care for long-term ventilator-dependent patients (i.e., length of stay usually exceeds 25 days). These patients may still require high levels of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) or FIO2. Once they are liberated from the ventilator or switched to a noninvasive method of support, these patients can then be transferred to a congregate living center or home.

Admission to a rehabilitation hospital is based on the patient’s specific rehabilitation goals. Current standards include the requirement for nursing rehabilitation care and at least two additional rehabilitation needs, such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, or speech therapy. After a 10-day trial period, patients must be able to participate for 3 hours of therapy per day.

Long-Term Care Sites

Long-term care sites include skilled nursing facilities, congregate living centers, and single-family homes. These sites do not have the resources to treat acutely ill patients. They are not the ideal site for weaning a patient from ventilation. However, they are the least expensive and provide a better quality of life and more independence for the patient.

Skilled nursing facilities include nursing homes, extended-care facilities, and convalescent centers. A greater number of VAIs are being placed in these locations.

Congregate living centers are commonly large private residences, apartments, foster homes, or homes with as many as six to 10 patients. These sites are more common in Europe than in the United States.1

Homes are the preferred location for ventilator-dependent patients. The quality of life is enhanced, and they are less costly than most other sites, perhaps with the exception of skilled nursing facilities. The family usually provides most of the support, both financial and medical.

Increasing pressure from managed care and utilization review is resulting in more rapid discharge from ICUs and acute-care facilities. Intermediate- and long-term care sites provide newer and less costly approaches to patient care.14–21 Treatment objectives are generally met at specific facilities. For example, weaning may occur in acute- or intermediate-care facilities, but it is usually inappropriate in the home.1

Patient Selection

Patient selection is the key to success for any long-care ventilation program. Although many factors must be considered in this selection, they can be broadly grouped into three areas:

Disease Process and Clinical Stability

Previous studies have shown that some patients with disorders requiring LTMV may be more successfully managed than others.22–25 The following three categories can be used to describe ventilator-dependent patients1,2:

3 Patients requiring continuous ventilatory support to survive, that is, patients diagnosed as having complete loss of ventilatory function with absent or severely impaired spontaneous breathing efforts. These patients are unable to sustain spontaneous ventilation and depend on life support from the ventilator. Their disorder is inexorably progressive. (Box 21-1 lists the disorders grouped in each category.)

Individuals who are considered candidates for LTMV in the home or in extended-care facilities must be clinically and physiologically stable to the degree that they are free from any medical complications for at least 2 weeks before discharge. Proof of medical stability must include stable cardiovascular and renal function; no evidence of uncontrolled hemorrhage or coma or, if comatose, prognosis for improvement; acceptable arterial blood gas (ABG) values; freedom from acute respiratory infections and fever; stabile FIO2 requirements; and ventilator settings which do not result in high inspiratory pressures or high levels of PEEP (Case Study 21-1).

Other considerations include the ability to clear secretions (either spontaneously or by suctioning), the ability to tolerate and meet criteria for a facemask or nasal mask for NIV, or the presence of a tracheostomy tube (TT) for invasive positive-pressure ventilation (IPPV). Additionally, major diagnostic tests or therapeutic interventions should not be anticipated for at least 1 month after discharge. Box 21-3 lists selection criteria for children.26

Psychosocial Factors

The psychological stability and coping skills of the patient and family are critical to the success of long-term ventilation. The family must be made aware of the patient’s prognosis and the advantages and disadvantages of LTMV.

In cases where the patient will be going home, a detailed psychological evaluation may be necessary to determine the ability of the patient and family to cope with stress.1,22 If the requirements for patient care exceed the family’s capabilities, professional assistance is essential. The availability of other support systems such as home health agencies, respite care, and psychological consultants are often critical to the success or failure of homecare candidates. The need for support and counseling is assessed before discharge and reassessed periodically while the patient remains on mechanical ventilatory support.27,28

Financial Considerations

Regardless of the location in which it is provided, mechanical ventilation is an expensive form of treatment. Note that mechanical ventilation in an ICU and acute-care unit is the most expensive option of the facilities previously mentioned, whereas homecare ventilation is the least expensive.14–17 It is important to recognize that despite the significant savings accrued when a patient receives ventilatory care in the home, the overall cost can strain family budgets, even for those who are insured.

A variety of factors can also influence the total cost associated with delivering LTMV. These factors include the following patient characteristics11,20:

For example, patients with COPD may require a higher level of care than patients with neuromuscular disorders because of the need for additional care such as suctioning, bronchopulmonary drainage, bronchodilator therapy, and anxiolytic and antibiotic administration. Children younger than 10 years may also require higher costs because of special needs compared with adults.

For homecare patients, ventilator equipment can be bought at a reasonable price; however, in many cases, families may choose to rent the ventilator because regular service, maintenance, and 24-hour emergency services are available as part of the rental contract. Unfortunately, the costs of accessory medical supplies, including items such as suction catheters, skin lotions, and absorbent underpads, may be the difficult to estimate and can significantly increase the total cost of care.

The major factor affecting the cost of home care is the need for professional or skilled caregivers. This cost depends on the availability of family members and how much they are willing and able to do. Cost also depends on patient independence and self-care abilities and the number of hours and level of care required from others.21

It is important to recognize that inadequate third-party coverage for supplies and equipment, which is almost always passed on to the patient and family, must be factored into the costs of providing LTMV in the home. An estimate of the actual cost to the patient must be determined as accurately as possible and presented to the patient and family before discharging the patient from the care facility to the home.

Preparation for Discharge to the Home

Respiratory therapists who are assigned to prepare a ventilator-assisted patient for transfer to another facility or home must ensure that the receiving site can accommodate the patient’s and family’s needs. Although similarities in discharge planning exist between an acute-care and an intermediate-care facility, the transfer from either of these facilities to the patient’s home requires particular attention.28,29

When the VAI is being transferred home, preparation is extremely important. Preparation of the home begins almost simultaneously with home and patient assessment and includes the process of equipment selection. The coordinated efforts of the multidisciplinary health care team, a comprehensive discharge prescription, and an educational program for the patient and caregivers are developed to ensure a safe transition from hospital to home or alternate care site (Key Point 21-2).

The discharge process may be complex and time consuming depending on the patient’s medical condition, needs, and goals. Consequently, it is initiated as early as possible before transfer to make it as smooth as possible. This often requires a minimum of a 7- to 14-day lead time because this much time may be needed to obtain insurance verification and authorization and equipment procurement. In other words, the plan may begin almost as soon as the patient is admitted to the acute-care facility or as soon as he or she is identified as a VAI. The discharge planning process ensures patient safety and optimal outcome in the new environment.

The goal of the discharge planning team is to identify all patient care issues that need to be addressed before discharge and develop a plan of care to facilitate transfer.1,29,30 The health care team generally consists of the patient and family, the patient’s primary physician, a pulmonary physician, a nurse, a respiratory therapist, and a social worker/hospital discharge planner. Depending on the patient’s level of care, other specialists, such as a physical therapist, a psychologist, an occupational therapist, a speech pathologist, and a clinical dietitian, might also be included. The durable medical equipment (DME) supplier will also be a crucial member of this team, and equipment should be selected as soon as possible. A coordinator should be designated if a hospital-based discharge planner is not available.31

Team members must communicate regularly to discuss the patient’s progress and address any issues that may hinder the discharge process. A thorough review of the patient’s chart is also important to determine the patient’s history and established medical condition. Ventilator settings are discussed to ensure that the DME supplier can provide a ventilator that can accommodate the desired settings. An assessment of the financial status of the patient is imperative to ensure that where gaps exist between third-party reimbursement and actual cost, additional assistance can be pursued.

Geographic and Home Assessment

The geographic area where the patient will reside should also be considered. This is done to ensure that a home health agency or DME provider is near the patient’s home and is available to provide assistance. A hospital emergency department should also be within a reasonable driving distance.

As part of the discharge plan, the medical supplier or practitioner assesses the patient’s home environment to see whether any modifications must be made before the patient goes home. In general, this assessment includes a home visit to view the size of the patient care area and determine whether it is adequate for the prescribed equipment. Areas should be available for storage as well as for cleaning and disposal of supplies. Judging the accessibility in and out of the home and between rooms is important and should not be overlooked. The home should also be assessed for safety (e.g., fire extinguishers and smoke detectors and alarms). The family needs to have telephone service. The number of people in the home may be a factor in the size of the space, and, of course, the primary caregivers are identified.

The electrical system must provide adequate amperage for the ventilation, suction equipment, oxygen concentrator if needed, and other necessary electrical devices. An important step is counting the number and type of electrical outlets and determining the amperage requirements of the equipment (Box 21-4). This may be accomplished by the family or it may require an electrician.32

When modifications in the home are recommended, they will not be covered by health insurance, which means that they will be out-of-pocket costs for the family. Therefore only absolutely necessary modifications should be made.33

Family Education

A written educational program is provided to caregivers and includes measurable performance objectives. At least three caregivers should be selected, with one being trained at a high enough level to be able to train and instruct other caregivers. Each discharge team member is responsible for educating the caregivers in specific areas of the management of the ventilator-dependent patient. The education component includes providing detailed instructions in the operation of the ventilator, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, the use of manual resuscitators, aseptic suctioning techniques, tracheostomy care, tracheostomy collars and humidification systems, methods of disinfecting equipment, bronchial hygiene therapies such as chest physiotherapy, aerosolized medication administration, bowel and bladder care, and bathing. The family is also taught to recognize the early signs and symptoms of a respiratory infection (assessment) and what action must be taken if such a situation arises. Part of this process requires that the caregivers stay in the acute care facility for 24 to 48 hours before discharge, providing total care to the patient under the supervision of the medical staff. Additionally, a written protocol with directions for respiratory treatments and other aspects of care is included.

Not all caregivers will be able to tolerate performing some procedures, such as suctioning, bladder and bowel management, or bathing. Not surprisingly, some people are intimidated by the ventilator. Patience is essential in family training. Sometimes additional family members or outside caregivers are needed. An adequate number of caregivers should be identified and trained to allow the family time for sleep, work, and relaxation. Outside caregivers may include the immediate family as well as extended family members, friends, nonprofessional paid caregivers, volunteers, and paid licensed health professionals.

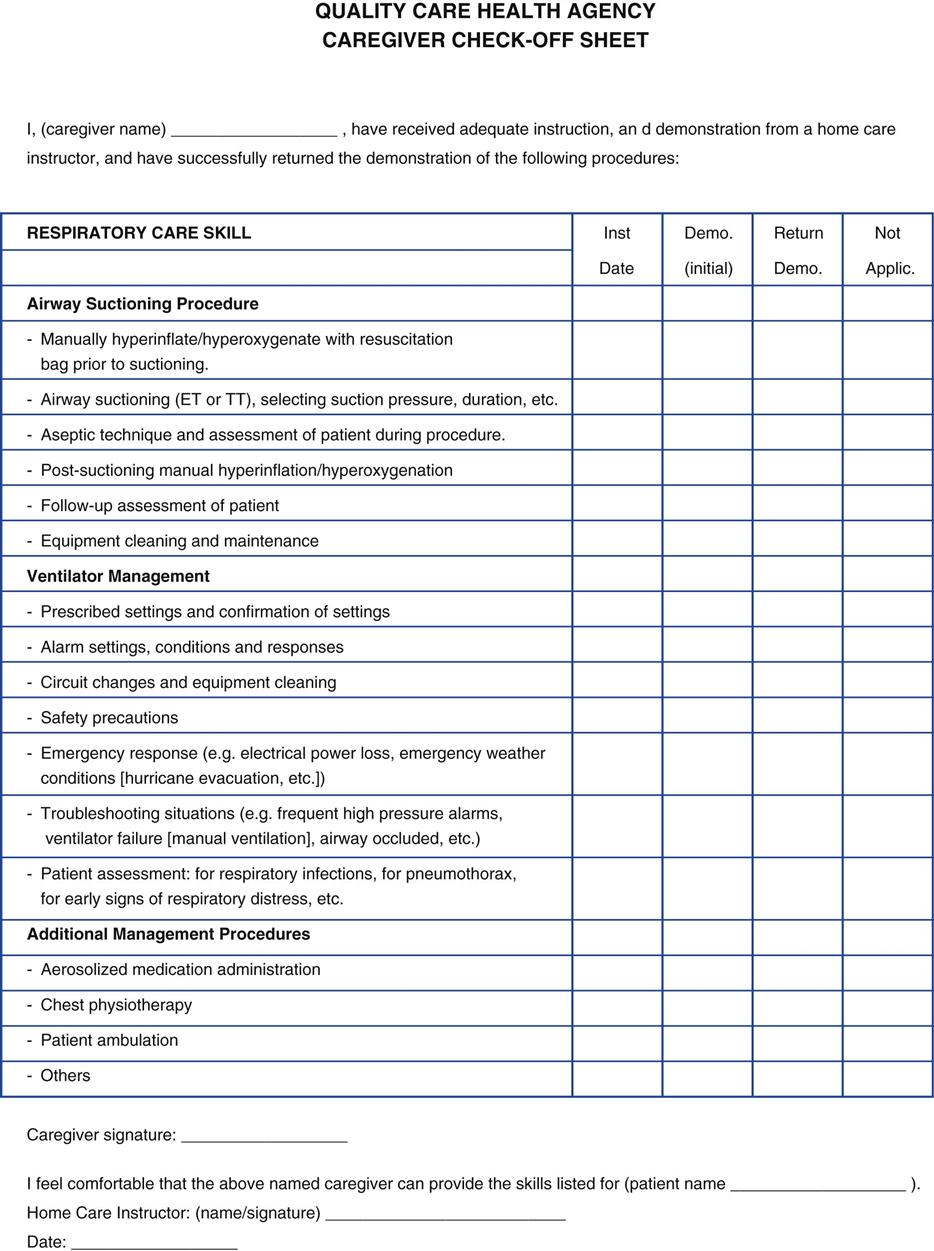

The respiratory therapist teaches the skills necessary for airway maintenance (suctioning and tracheostomy care), ventilator settings, circuit maintenance, infection control, troubleshooting the equipment, and emergency measures. A basic checklist of these skills is given to the patient and family and used to guide the educational process. All family members involved in the patient’s care need to demonstrate adequate hands-on performance of all aspects of patient care before the patient is discharged. Figure 21-1 is an example of a caregiver assessment sheet. Once these tasks are learned and competencies are demonstrated, the patient is placed on the home ventilator several days before discharge, allowing family members to become comfortable with the process.

Additional Preparation

The primary physician usually makes arrangements with a local physician and nursing service if the patient lives far away. The local hospital emergency department should be designated for emergency care, with an emergency plan clearly outlined. The local power company must be notified in writing of the patient’s condition. The patient’s home will need a priority status for electrical power service in case of a power failure.

The family and patient must also be prepared for emergency situations such as fires, hurricanes, tornados, flooding, and so forth. A contingency plan must be in place if power loss occurs from any of these disasters. A disaster may require evacuating the patient from the home to a special-needs shelter. Because of these possibilities, local fire departments, emergency medical teams, utility companies, police departments, and the local hospital emergency department should all be aware of the patient’s urgent medical needs.

Follow-Up and Evaluation

Before the patient is discharged, equipment and supplies are set up in the patient’s home or another care site and checked for proper placement and function. Members of the discharge planning team assist with the transfer from the acute care facility to the intermediate-care facility or from the intermediate-care facility to home or another alternative long-term care facility.

When a transfer to home is being coordinated, practitioners from the homecare company must be present. They can assist with the transfer to the ambulance and from the ambulance to the home. Homecare practitioners must be present when the patient arrives home to reassure the patient and family and alleviate any apprehensions.

Part of the assessment of the patient involves how the patient feels about his or her interaction with the ventilator once he or she arrives home. Simple but key questions to ask include the following34:

• Are you getting a deep enough breath?

• Does the breath last long enough?

• Do you have enough time to get all your air out?

Initially patients may require frequent home visits or daily calls until they are stable and adjusted to a routine of care. Once this routine is established, only formal monthly visits are necessary to evaluate the patient and report on progress. Box 21-5 reviews follow-up and evaluation of infants and children. Evaluations during home visits may include patient assessment parameters such as bedside pulmonary function studies, vital signs, and pulse oximetry. Assessment in the home does not generally include ABG studies.

Assessment may also include observation of the home environment and assessment of the equipment and any other problems the patient or family members may have. In some cases other health care providers may need retraining. For example, a homecare nurse may be disposing of the TT after each weekly visit, not realizing this was not appropriate. Another example involves a family member calling the homecare respiratory therapist because of a frequent high-pressure alarm. In this latter example, the family needs retraining about how to identify when suctioning is needed.

A written report is completed after the monthly visit, and copies are sent to the patient’s physician, homecare agency, and other members of the health care team. This report might include the following:

• Identification of company, servicing location, date, and time

• Patient name, address, phone, e-mail

• Prescribed equipment and procedures

• Caregiver and patient (if possible) comprehension of equipment and procedures

• Compliance with plan of care

The task of caring for ventilator-dependent patients often creates frustration and anxiety for family members who are the primary caregivers. If problems are identified during home visits, the patient’s physician should be notified. It may be necessary to provide psychological counseling to family members or suggests an alternative means of care (e.g., respite care) to allow family members time to rest.

Adequate Nutrition

Another aspect that must not be ignored is the nutritional status of the patient. Food intake is critical in avoiding problems associated with poor nutrition, such as increased risk of infection (e.g., pneumonia) and weakened muscles, including the diaphragm.35 Caregivers should have a general idea of the patient’s food and fluid intake as well as output. Constipation and bowel impaction need to be avoided. Some patients are at risk for aspiration when taking food by mouth, in which case a preferred feeding route might be through a gastrostomy tube or a jejunostomy tube.

Family Issues

Despite all efforts to discharge patients successfully to home, some factors may be difficult to manage. Significant delays in discharge from the hospital may occur if organizing the discharge plan or providing adequate funding is not possible.4,33 Often one or more family members will lose employment time when a patient is discharged to home. This can worsen the family’s financial position. Planned funding may have been based on the family’s budget before discharge.

In addition, the respite for family caregivers may not be adequate. Getting extended family members and friends to help will not be successful unless these individuals are adequately trained in the care of the VAI. When caregivers from outside the family are in the home 24 hours a day, this erodes family privacy and can also be stressful.36 When external caregivers take vacation or sick days, the family caregivers often have to step in to provide additional coverage.

Careful, well-planned, and timely organization are absolutely essential to success in discharging a VAI from an acute-care facility to home or a skilled nursing facility. Patient and home assessment, caregiver education and training, and demonstration of care by caregivers are all important elements. Box 21-6 lists the primary components of a discharge plan for sending the patient home on long-term ventilation.33

Equipment Selection for Home Ventilation

When patients are transferred to their home, equipment setup, instructions, and planning are especially important. Families must have immediate access to all required equipment and supplies. Box 21-7 provides a preliminary checklist of equipment for care of the mechanically ventilated patient in the home.1,21

It should be apparent that the most important equipment to be selected is the ventilator. Selection depends on the goals for the particular patient. Ventilation can be provided by IPPV in patients with a tracheostomy tube. IPPV is indicated for patients who have persistent symptomatic hypoventilation. It is also indicated for patients who do not meet selection criteria for NIV or who are unable to tolerate NIV or other types of noninvasive support such as negative-pressure ventilation (NPV).

This section reviews ventilator selection for IPPV and NPV and the use of noninvasive devices, such as the rocking bed and the pneumobelt, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices, and noninvasive devices for secretion clearance. The use of NIV is discussed in Chapter 19.

Tracheostomy Tubes

The use of a TTs is essential for invasive LTMV. Generally a tracheotomy is performed as soon as possible once the need for extended intubation is verified and it appears the patient is likely to benefit from the procedure. This usually occurs when a patient is stabilized on the ventilator in an acute-care hospital within about 7 days of the onset of respiratory failure or sooner in patients who are neurologically impaired.37–39 Chapter 20 reviews the role of tracheostomy in ventilator discontinuation. The use of speaking tubes and devices for patients with long-term tracheostomies is explained later in this chapter.

Ventilator Selection

Many types and models of ventilators are available for home use. Some of these are quite sophisticated, offering an array of modes, alarm systems, and other complex ventilatory characteristics. Although these machines may occasionally be necessary for medical stability outside the hospital, simple technology should be the goal of ventilator selection when it is possible.34,40

The most important factors in choosing a ventilator are the following:

For all home ventilator patients, backup ventilatory support must be available in case of electrical failure or malfunction. All ventilator-assisted patients require a self-inflating manual resuscitator. If a patient can maintain spontaneous ventilation for 4 or more consecutive hours, a manual resuscitator may be all that is necessary as a backup.32,41 For patients who are totally dependent on ventilatory support or those who live far from medical support, a second mechanical ventilator is necessary as a backup. Those patients who require supplemental oxygen also need a concentrator and an E-cylinder as a backup.

Examples of Home Care and Transport Ventilators

A positive-pressure ventilator is the most commonly used device for providing ventilatory support for the homecare patients. Unlike the large and sophisticated positive-pressure ventilators used in the ICU, these easy-to-operate ventilators for home care have an array of advantages, notably compact size, light weight, and portability. Most of these units are designed to use three different power sources: normal AC current, internal DC battery, and external DC battery. Ventilators that use an external DC battery can be mounted relatively easily on a wheelchair or placed in a motor vehicle, enhancing a patient’s capability of mobility and participation in other activities.

Many homecare positive-pressure ventilators have been developed in the past three decades. This text cannot completely describe all of the available features of each ventilator, but a brief review is provided. Most of these units are described elsewhere.41 Box 21-8 lists several examples of homecare and transport ventilators.