History of Fetal Monitoring

Dt is somewhat surprising that something as potentially accessible as the fetal heart was neither heard nor described until the 17th century when Phillipe LeGaust first depicted fetal heart tones in his poetry in an ancient French dialect. LeGaust was a colleague of Marsac, a physician of the province of Limousin, who is credited with first having heard the fetal heart.

Marsac’s observation apparently went unnoticed until 1818, when Swiss surgeon Francois Mayor reported the presence of fetal heart sounds when he placed his ear on the maternal abdomen in an attempt to hear the fetus splash about in the liquor amnii. Three years later, French nobleman Lejumeau Kergaradec, apparently unaware of Mayor’s report, described both the fetal heart tones and the uterine souffle. He suggested auscultation to be of value in the diagnosis of pregnancy and twins and in determining fetal lie and presentation.

As with many discoveries, the obstetricians of the time were slow to respond to Kergaradec’s observations and recommendations. To convince clinicians of the value of Kergaradec’s findings, Evory Kennedy of Dublin published an extensive book in 1833, Observations on obstetric auscultation (1). The text contains many anecdotal examples of cases in which auscultation was clearly beneficial. In addition, Kennedy described the funic souffle for the first time.

THE FETOSCOPE

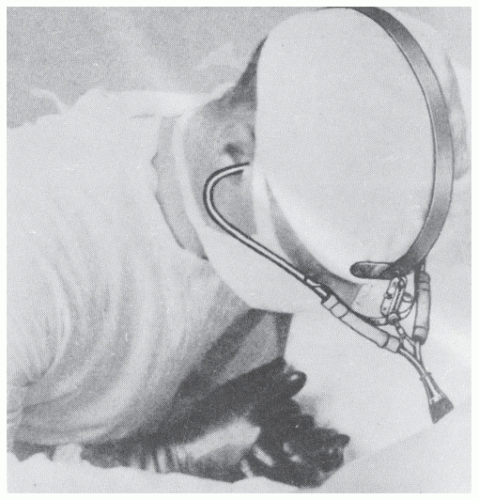

Before the development of the fetoscope, much attention was paid to whether mediate (stethoscopic) auscultation using Laennec’s instrument, or immediate auscultation, with direct application of the ear to the gravid maternal abdomen, was the more appropriate choice. Rauth and Verardini (2) suggested vaginal stethoscopy as more valuable in the early detection of fetal life. The development of the head stethoscope (fetoscope) is a story of controversy and professional jealousy. It was first reported, in 1917, in The Journal of the American Medical Association (Fig. 1.1), by David Hillis (3), an obstetrician then working in Chicago Lying-In Hospital. In 1922, J.B. DeLee (4), who was chief of staff at the same institution and who became a legend in American obstetrics for many contributions, published his report of a similar instrument. Although the order of publications is clear, DeLee claimed that he openly talked of this idea for many years preceding the Hillis publication. The instrument, which subsequently came to be known as the DeLee-Hillis stethoscope, has changed little since its early development.

DIAGNOSIS OF FETAL DISTRESS

Thirty years after Mayor first described heart sounds, Kilian (5) first proposed that changes in the fetal heart rate (FHR) might be used to diagnose fetal distress and to indicate when the clinician should intervene on behalf of the fetus. He formulated what is sometimes called “the stethoscopal indication for forceps delivery” and suggested that heart rates below 100 or above 180 beats per minute (BPM) and those with loss of purity of tone or distinct intermission, or in which only one tone could be heard, were indications for forceps application without delay. In 1893, Von Winckel (6) described the criteria of fetal distress that were to remain essentially unchanged until the arrival of fetal scalp sampling and electronic heart rate monitoring: tachycardia (heart rate >160 BPM), bradycardia (<100 BPM), irregular heart rate, passage of meconium, and gross alteration of fetal movement. Few studies either challenged or supported the validity of these auscultative and clinical criteria for fetal distress. It was not until 1968, when Benson et al. (7) published the results of the Collaborative Project, commissioned by the National Institute of Neurologic Diseases and Blindness, that these criteria came under serious scrutiny. The Benson study reviewed the benefits

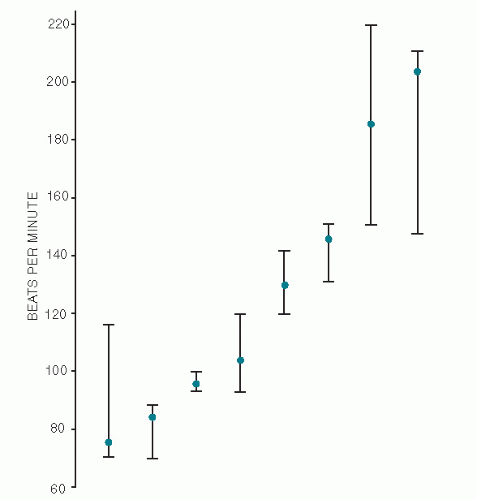

of FHR auscultation in the management of intrapartum fetal distress in 24,863 deliveries. Benson concluded that there was “no reliable indicator of fetal distress in terms of fetal heart rate save in extreme degree.” Ten years earlier, Hon (8) asked 15 obstetricians to count several rates from audiotape. He found a wide divergence in counting and pointed out the unreliability of human computation of the FHR (Fig. 1.2).

of FHR auscultation in the management of intrapartum fetal distress in 24,863 deliveries. Benson concluded that there was “no reliable indicator of fetal distress in terms of fetal heart rate save in extreme degree.” Ten years earlier, Hon (8) asked 15 obstetricians to count several rates from audiotape. He found a wide divergence in counting and pointed out the unreliability of human computation of the FHR (Fig. 1.2).

Figure 1.1. Original illustration of the head stethoscope or fetoscope. (From Hillis DS: Attachment for the stethoscope. JAMA 68:910, 1917.) |

As new information has emerged, the term fetal distress has been determined as an inappropriate term to describe FHR patterns that may be associated with decreases in fetal oxygenation. Because a large proportion of such patterns do not result in neonates with signs of fetal hypoxia and/or acidosis, the term nonreassuring FHR pattern has been adopted to refer to such tracings. In addition, the original recommendations for intervention based on periodic FHR patterns alone are undergoing an evolution in which the presence of spontaneous or evoked accelerations, FHR variability, fetal pH, and fetal pulse oximetry allow the clinician to sometimes avoid intervention for nonreassuring patterns. These approaches will be discussed in later chapters.

With these serious doubts, and with the age of electronic technology fast making its impact on modern medicine, it was inevitable that obstetric research would turn to more sophisticated methods of fetal evaluation.

THE FETAL ELECTROCARDIOGRAPH

Cremer (9) recorded the FHR electronically for the first time in 1906, by means of abdominal and intravaginal leads. For the first half of the century, the application of fetal electrocardiography was used primarily for the diagnosis of fetal life. It was Southern (10) who, in 1957, suggested that certain fetal electrocardiograph (ECG) changes might correlate with fetal hypoxia. Shortly thereafter, Hon and Hess (11) reviewed all the applications of fetal electrocardiography, including fetal presentation, diagnosis of twins, antenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease, diagnosis of fetal maturity, and fetal distress. They concluded that the ECG waveform was not of consistent value in any of these situations and, specifically, that in 75 cases of fetal distress “no consistent fetal ECG changes could be detected.” Subsequently, Pardi et al. (12) used group averaging techniques to demonstrate ST segment depression with fetal hypoxia (Fig. 1.3). Unfortunately, this technique has not been developed to the point where it has become clinically applicable.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree