Antepartum Management of the High-Risk Patient

The previous chapter was devoted to introducing antepartum fetal surveillance, including fetal heart rate (FHR) testing and biophysical profile (BPP); describing methodology; interpretation; and understanding the associated limitations and pitfalls. The appropriate application of these methods in various clinical situations is critically important.

First, we must decide which patients require antepartum testing. Almost half of the antepartum deaths occurring beyond 26 weeks’ gestation are in patients at risk for some form of uteroplacental insufficiency (UPI) (1,2). Patients at increased risk for UPI comprise approximately 10% to 20% of the prenatal population, and various means have been used to attempt to correctly identify these women (3). The other half of antenatal deaths, however, occur in patients who would generally be classified as low risk. Lowrisk women make up the majority of the obstetric population. One choice is to limit antepartum fetal surveillance to the 10% to 20% of patients at risk for UPI and thereby attempt to prevent this one-half of fetal deaths. Another choice is to test all patients in an effort to attempt to avoid all fetal deaths. This latter choice is an extreme alternative, and there is no study that shows a benefit to the routine fetal testing (beyond fetal movement assessment) of all low-risk patients. The more reasonable and well-accepted approach for identifying the low-risk patient destined to have a fetal death is to carefully observe all patients for normal fetal growth and fetal movement. Many patients with unexpected fetal death will have a growth-restricted fetus. Thus, the general approach is to routinely measure fundal height in all patients receiving prenatal care and evaluate the fetus with ultrasound when the fundal height is significantly less than expected. In addition, although not necessarily recommended, most patients do have a routine ultrasound in the second or early third trimester. When these examinations, for whatever reason, suspect intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), antepartum testing becomes indicated. Routine fetal movement testing has been shown in large well-controlled studies to decrease the rate of antepartum fetal deaths in low-risk patients (4,5). Thus, all patients should be counseled at some time in the early third trimester to do some kind of daily assessment of fetal movement (Fig. 12.1). There is a great deal of variation in the exact method used for fetal movement counting, as outlined in the previous chapter. Regardless of the specific method chosen, when the patient calls with absent or substantially reduced fetal movement, and when this has been confirmed by having her concentrate for an hour or two in a quiet room, the patient must come in for an immediate nonstress test (NST) regardless of the time of day. Keep in mind, however, that whatever the indication, testing should be implemented only when a gestational age is reached where the clinician, if faced with definitely ominous data, is ready to intervene. Thus, in the 80% of otherwise low-risk patients, the main indications for testing are the development of suspected IUGR and decreased or absent fetal movement. In the remaining highrisk patients, the indications for antepartum FHR testing are summarized in Table 12.1.

TESTING PROTOCOL BY CLINICAL SITUATION

We shall attempt to describe an approach to antepartum testing in terms of categories of risk and specific diagnoses or risk factors that place the patient at increased risk for fetal death from UPI. We shall present our approach to antepartum testing and use this format to provide examples for illustration. It should be clear that there are many different approaches in terms of when to begin testing, when to intervene, different ancillary tests, etc. The approach presented here is based on extensive clinical experience with antepartum heart rate testing in high-risk patients and on data that have been published by the authors and many others (1,6,7).

Which Test to Use

Controversy exists as to which form of antepartum surveillance provides optimal results. Issues such as patient population, available facilities, cost, convenience, testing interval, and the specific indication for testing must be considered when selecting the particular means of fetal assessment for your patient.

As described in the previous chapter, the most frequently used method for primary surveillance is the modified biophysical profile. The NST is almost always performed at least twice weekly. The frequency of the amniotic fluid (AF) volume assessment may be once or twice weekly. In a review of a large series of amniotic volume testing, Lagrew and coworkers found that in patients with an amniotic fluid index (AFI) of 8 cm or greater, a change to significant oligohydramnios (AFI <5) rarely occurred in less than a week, except in patients with IUGR and who go beyond 41 weeks (8). Thus, it is logical to test these latter two groups of patients and those with borderline AFI (5.0 to 7.9 cm) with twice-weekly NSTs and AFIs and the remainder with twiceweekly NSTs and once-weekly AFIs. One group of patients that we approach differently are those with diabetes for reasons described in the following section. In general, other tests of fetal well-being are then reserved for “backup” testing in those patients with an abnormal NST or AFI result (Fig. 12.2). The one exception perhaps is with Doppler testing of umbilical artery flow. This modality may have additional utility in clarifying the diagnosis of IUGR and prognosticating which fetuses are destined to require early delivery.

Moderate-Risk Groups

There is a group of conditions in which the risk for fetal death from UPI is only moderately increased above that of the low-risk population. Furthermore, in this group, fetal death tends to occur late in gestation. Thus, in general, for these patients, we recommend beginning testing at approximately 34 weeks. These clinical situations include advance maternal age, maternal hyperthyroidism, and previous stillbirth. Women over the age of 35 years have previously been thought to represent a risk group for whom fetal surveillance is indicated. However, at least up to the age of 40 years, unless the pregnancy is complicated by diabetes, hypertension, or other problems, women do not have any increased risk for stillbirth or abnormal FHR tests secondary to UPI (9,10).

Women with a diagnosis of hyperthyroidism or a history of hyperthyroidism may be at risk for fetal compromise. The etiologic agent is a thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin of the IgG class. Thus, this antibody can cross the placenta and cause fetal hyperthyroidism and tachycardia. Women with a history of hyperthyroidism who are euthyroid following an ablative procedure (i.e., surgery or radioactive iodine) may still have the antibody present during a subsequent pregnancy, with potential fetal compromise. Even without the fetus

being directly involved, poorly controlled hyperthyroidism may divert blood and oxygen from the fetus because of the increased metabolic demands of maternal tissues. For these reasons, we recommend testing in these women. Similarly, women with a history of an unexplained stillborn are begun on fetal surveillance at some point before the gestational age at which the loss occurred. Although this primarily provides maternal reassurance, we have found an increased incidence of abnormal test results in these patients, particularly in women with a history of previous stillbirth associated with a current diagnosis of hypertension or suspected IUGR (11,12).

being directly involved, poorly controlled hyperthyroidism may divert blood and oxygen from the fetus because of the increased metabolic demands of maternal tissues. For these reasons, we recommend testing in these women. Similarly, women with a history of an unexplained stillborn are begun on fetal surveillance at some point before the gestational age at which the loss occurred. Although this primarily provides maternal reassurance, we have found an increased incidence of abnormal test results in these patients, particularly in women with a history of previous stillbirth associated with a current diagnosis of hypertension or suspected IUGR (11,12).

TABLE 12.1 Indications for antepartum fetal surveillance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Postdate Pregnancy

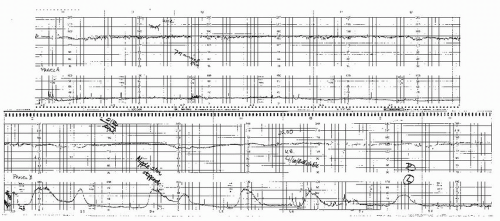

In most series, “postdate” pregnancy is the condition accounting for the majority of patients undergoing antepartum testing. Often this is because many patients have wrong dates. Postdate testing is relatively controversial, primarily from the standpoint of when to begin testing and when to deliver. Studies of contemporary practice suggest that the majority of practitioners will recommend delivery for patients at or beyond 41 weeks with a favorable cervix and for all patients after 42 weeks regardless of the condition of the cervix (13), which is our practice as well. Although the data suggest no substantial increase in asphyxia or stillbirth until after 42 weeks, a relationship exists between the incidence of abnormal antepartum testing results and advancing gestational age with positive test results increasing at and after 41 weeks (14) (Fig. 12.3). Thus, we begin testing at 41 weeks. Postdate patients also have a high frequency of oligohydramnios. Oligohydramnios (AFI <5.0 cm) in a patient with a well-dated pregnancy beyond 41 weeks is virtually always an indication for delivery. The FHR during an NST or contraction stress test (CST) in patients with oligohydramnios will frequently demonstrate recurrent prolonged or variable decelerations, as the protection the fluid offers the umbilical cord is diminished. Such patients pose an additional dilemma as cervical ripening agents often result in uterine hyperstimulation and prolonged cord compression. Often, it is wise to precede the placement of the ripening agent with a negative CST result, which can indicate how well the fetus will tolerate uterine contractions. If there are decelerations associated with contractions in such patients, it is preferable not ripening at all or alternatively to choose an agent that is not likely to result in uncorrectable prolonged contractions (e.g., Foley catheter). Currently, it appears that most clinicians use the modified BPP for primary surveillance in the postdate pregnancy. As previously mentioned, we perform twice-weekly NSTs and AFIs in these patients. Because the only reason not to deliver these patients is an unfavorable cervix, which may increase the likelihood of failed induction and cesarean section, the threshold for delivery for abnormal tests is relatively low in this group of patients (15,16). Certainly, a positive CST result or low BPP (4 or less) is an indication for delivery (16,17 and 18). Most often, however, these patients will be delivered for a low AFI and/or significant variable or prolonged decelerations. In these patients, these less ominous results may also be an indication for delivery since the only reason not to deliver the postdate patient is the risk of failed induction and cesarean section, and thus, the risk benefit ratio requires less impetus to weigh in favor of delivery.

Preeclampsia

Preeclampsia is a disease for which it is particularly difficult to outline a routine for antepartum evaluation. This is because management is more often guided by maternal condition than by fetal condition. Conservative treatment of the maternal disease (i.e., bed rest) can improve fetal condition, and, conversely, deterioration of the maternal condition can result in worsening UPI. Gant et al. (19,20) showed that UPI precedes the clinical manifestations of preeclampsia by 1 to

3 months. The fact that IUGR can be seen in patients many weeks before developing signs and symptoms of preeclampsia corroborates these data.

3 months. The fact that IUGR can be seen in patients many weeks before developing signs and symptoms of preeclampsia corroborates these data.

Antepartum testing in patients with preeclampsia should be conducted with the following basic rules in mind:

Fetal jeopardy may exist even in the patient whose blood pressure normalizes at bed rest.

The clinical condition may change rapidly. Should such changes occur, repeat evaluation of the fetus must be performed even when the most recent assessment was reassuring.

Fetal condition is but one variable in the equation of evaluation and management of these patients.

Occasionally, abnormal antepartum heart rate patterns improve when the maternal condition significantly changes for the better (e.g., control of severe hypertension).

Patients with severe preeclampsia require continuous monitoring of FHR even if the decision is made to delay delivery for extreme prematurity or to take the time to administer corticosteroids.

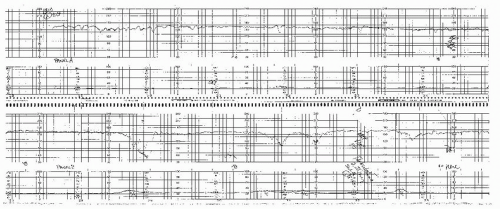

Antepartum fetal monitoring is begun when the disease is first recognized and viability is considered likely. In our institution, this is around 24 weeks’ gestation (Fig. 12.4). As with other antepartum conditions, testing should occur every 3 to 4 days using the modified BPP, although AF volume can be assessed every week if the previous value was normal (≥8 cm). If the preeclampsia is severe and the patient is not being delivered in an effort to gain additional maturity, consideration should be given to daily NSTs or continuous monitoring because the situation is very dynamic.

Chronic Hypertension

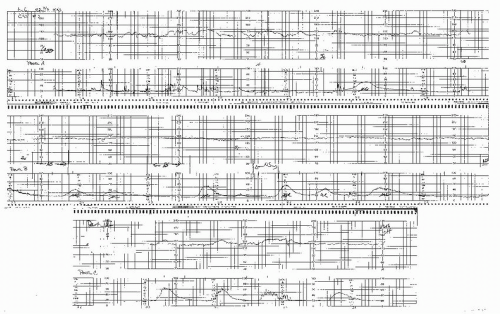

In terms of fetal jeopardy from UPI, chronic hypertension, especially when poorly controlled, is one of the most profound antepartum risk factors. Many cases of chronic hypertension are complicated with IUGR. In these cases, the risk is especially high, and fetal death may occur at any point. Consequently, we recommend initiation of antepartum surveillance beginning as early as 26 to 28 weeks in these patients, or sooner if there is suspicion of IUGR (21). As with other patients, testing can be conducted using the modified BPP with the NST done every 3 to 4 days and the AF volume assessed weekly unless there is IUGR or the previous value is <8 cm, where AF volume should be checked at least twice weekly. Often, when beginning testing in early gestation, the fetus may be nonreactive because of gestational age. It is reasonable to start with an NST regardless because 50% of fetuses will meet criteria for reactivity by 24 to 26 weeks (22). Some modification of the definition of reactivity may be made for gestations of <32 weeks. One should also use the patient as her own baseline because those fetuses that were

previously reactive will not become nonreactive because of immaturity. Patients with chronic hypertension and reassuring fetal surveillance, stable blood pressure, and no evidence of IUGR can be delivered at 38 weeks or later.

previously reactive will not become nonreactive because of immaturity. Patients with chronic hypertension and reassuring fetal surveillance, stable blood pressure, and no evidence of IUGR can be delivered at 38 weeks or later.

Many patients with chronic hypertension develop superimposed preeclampsia. These patients should then be treated as preeclamptics. Patients with chronic hypertension are also at risk for placental abruption; this cannot be predicted, but vaginal bleeding or premature uterine activity requires immediate fetal evaluation with the potential of abruptio placentae in mind.

Patients with chronic hypertension may require changes or adjustments in their medications to control blood pressure during pregnancy. Commonly used antihypertensive medications are beta-blockers, which, among other things, may affect the amount of reactivity of the FHR, especially in high doses. This must be considered when attempting to interpret FHR information either antepartum or intrapartum in patients taking these medications. Another important point regarding hypertension control and FHR monitoring is that when patients with chronic hypertension develop sudden deterioration of their blood pressure control, or in patients with severe preeclampsia, acute lowering of blood pressure may adversely affect uterine perfusion. Care should be taken to avoid rapid reduction to normal or below normal blood pressure because the fetus may become acutely hypoxic and will exhibit late decelerations with too vigorous antihypertensive therapy (see Figure 8.33). Continuous monitoring of FHR while treating severe hypertension is critically important to ensure adequate placental perfusion and identify possible fetal distress. Indeed, using FHR information is of great assistance in establishing an acceptable blood pressure endpoint for both fetus and mother.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree