Heart-Lung Transplantation

Ahmad Y. Sheikh

Hari R. Mallidi

Robert C. Robbins

INTRODUCTION

Heart-lung transplantation represents the last hope for a small group of patients with severe combined end-stage disease. It was performed successfully at Stanford University in 1981, and these patients were the first to be completely supported by transplanted lung grafts. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation reports that >3,000 heart-lung transplants have been performed worldwide. In the earlier years, this included patients with primarily lung disease, such as emphysema or cystic fibrosis; more recently, it has been restricted to end-stage disease of both organs, such as patients with congenital heart disease and pulmonary vascular disease (Eisenmenger syndrome), or severe primary pulmonary vascular disease with end-stage right heart failure (Cor pulmonale). In addition, at our center, we have successfully transplanted patients with primary lung dysfunction in the setting of end-stage ischemic heart disease. About 20 to 30 heart-lung transplant procedures are performed yearly in the United States, with an additional 30 to 50 performed in the rest of the world.

RECIPIENT SELECTION

The primary objective in recipient selection is to identify individuals with progressively disabling cardiopulmonary or pulmonary disease who still possess the capacity for full rehabilitation after transplantation. Heart-lung transplantation has a greater potential for technical complications than either heart transplant or lung transplant alone, so that it is particularly important to have stricter recipient selection criteria to assure a reasonable chance of a successful outcome. To this end, older recipients (>60 years of age) have not usually been selected for heart-lung transplantation, whereas they are frequently candidates for heart transplant. Significant multisystem disease is a contraindication, although combined heart-lung and liver, or combined heart-lung and kidney, transplantation has been successfully performed. Contraindications include renal dysfunction, active malignancy, infection with HIV, hepatitis B or hepatitis C, severe liver disease, cachexia or obesity, drug or alcohol abuse, and inability to cooperate with treatment programs. Patients who have had previous thoracic surgery are evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Multiple previous thoracotomies or pleurodesis are not absolute contraindications, although they might represent higher risk for surgical teams without significant experience in performing the operation. A patient who is acutely ill in the intensive care unit and specifically on mechanical ventilation is generally considered to be too ill to undergo heart-lung transplantation.

Patients accepted for transplantation are listed on the National Transplant Registry on the basis of diagnosis, time on the waiting list, and ABO blood group. Because heart-lung transplant recipients are in competition with critically ill heart recipients who may have a more urgent status, the number of potential donors offered is low. The additional requirement for lung volumes of approximately equal or slightly smaller size further limits the potential donor pool. Like lung transplantation alone, patient height is a reasonable predictor for lung volume, and donors of significantly greater height should be avoided. The presence of preformed reactive antibodies (PRA) at a level of >25% requires a prospective specific cross-match between the donor and recipient. The presence of a significantly elevated PRA will require specific measures, either pretransplant or posttransplant, to reduce the likelihood of hyperacute rejection of the donor organs, such as plasmapheresis and alternative immunosuppression. Diligent surveillance is also mandated in these patients to avoid the sequelae of late humoral rejection.

ORGAN PROCUREMENT AND PRESERVATION

Currently, all heart-lung block donors have sustained irreversible brain death but retain near-normal heart and lung function. Standard donor evaluation is performed, including physical examination, chest X-ray, 12-lead electrocardiogram, arterial blood gases, and serologic screening. A donor age of <50 years is preferred. Coronary angiography may be indicated in donors >40 years of age or with cardiac risk factors. Meticulous fluid management prevents excessive pulmonary edema and improves pulmonary and myocardial function. The last decade has seen significant progress toward better donor management, such that initially poor lung and heart function can be improved with aggressive treatment. Because of the already greater technical complexity of the heart-lung transplant operation, good donor organ function is extremely important. The criteria for donor selection are listed in Table 64.1.

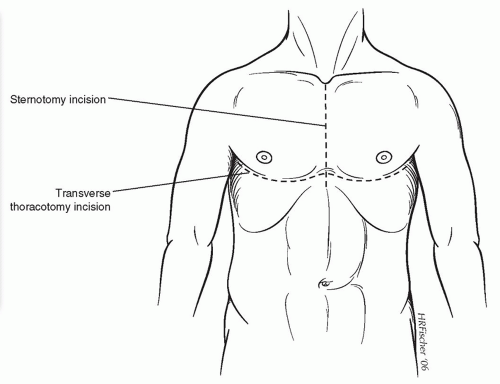

The donor operation is performed via a median sternotomy, as shown in Figure 64.1. Some harvests may also be done with a bilateral transverse thoracotomy as shown, depending on the requirements of the abdominal organ teams. Both pleural spaces are immediately opened with inspection of both lungs carried out. The heart is inspected, to rule out significant contusions and anatomic anomalies. This is followed by palpation of the coronary arteries to rule out significant coronary artery calcifications. The lungs are briefly deflated, and the pulmonary ligaments are divided using electrocautery. After completely dissecting and removing the thymic remnant, the pericardium is removed to within about 2 cm of the phrenic nerves bilaterally. Umbilical tapes are placed around the ascending aorta and both venae cavae. The pericardium overlying the trachea is incised vertically, and the trachea is encircled in the superior part of the mediastinum at least five or six

complete tracheal rings above the carina. This maneuver can be facilitated by ligating and dividing the innominate vein.

complete tracheal rings above the carina. This maneuver can be facilitated by ligating and dividing the innominate vein.

Table 64.1 Heart-Lung Donor Selection Criteria | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

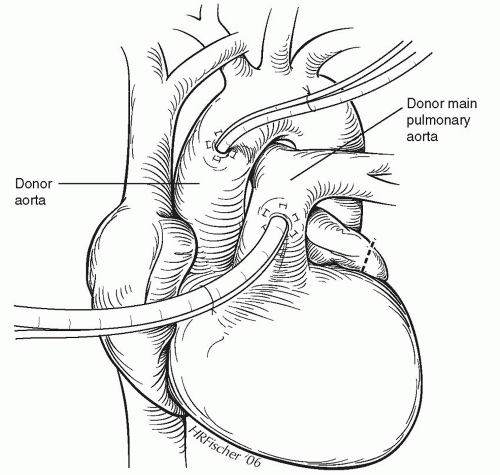

An infusion of prostaglandin E1 is started approximately 15 minutes before applying the aortic cross-clamp, beginning at a rate of 20 ng/kg/min, followed by incremental increases, to a target rate of 100 ng/kg/min. Careful monitoring of the mean arterial blood pressure should assure that it remains above 50 mmHg. Ventilation continues with a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 40% and a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) (3 to 5 cm of water). Infusion lines are placed in the ascending aorta and the main pulmonary artery, as shown in Figure 64.2. The donor is then heparinized, the superior vena cava is ligated, and a straight Potts clamp is placed across the inferior vena cava. After the heart empties, the aortic cross-clamp is applied, and 10 ml/kg of cold crystalloid cardioplegia is rapidly infused into the aortic root. We prefer the Stanford formulation, but several other cardioplegia solutions are available. The inferior vena cava is then incised, and the tip of the left atrial appendage is amputated (Fig. 64.2), to avoid cardiac and lung distention from the return of the pulmonary perfusion. While antegrade cardioplegia is being delivered, a separate pulmonoplegia is flushed through the main pulmonary artery at a rate of 15 ml/kg/min for a period of 4 to 5 minutes. Ice-cold saline or Physiosol solution (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) is immediately poured over the heart and lungs. During the cardioplegia and pulmonoplegia infusions, ventilation

is maintained with half-normal tidal volumes of room air. On completion of these infusions and topical cold application, all solutions are aspirated from the thoracic cavity, and the lungs are fully deflated.

is maintained with half-normal tidal volumes of room air. On completion of these infusions and topical cold application, all solutions are aspirated from the thoracic cavity, and the lungs are fully deflated.

The heart-lung block is dissected free from the esophagus, commencing at the level of the diaphragm and continuing cephalad to the level of the carina. Dissection is kept close to the esophagus, and care is taken to avoid injury to the trachea, lung, and great vessels. The posterior hilar attachments are divided and the lungs inflated to a half-normal tidal volume, and the trachea is stapled at the highest point possible with a TA-55 stapler (United States Surgical, Norwalk, CT) at least four rings above the carina. The trachea is then divided above the staple line, and the entire heart-lung block is removed from the chest. After the heart-lung block is removed from the donor, it is wrapped in sterile gauze pads and immersed in ice-cold saline between 2°C and 4°C, placed in several sterile plastic bags, and then placed in a sterile plastic container. This is placed in an ice-filled insulated box and transported to the transplant center. Because nonpressurized aircraft might be employed, we believe it is important to avoid overdistention of the lung before stapling of the trachea, to prevent overexpansion during transport, especially if air transport is required.

With current preservation techniques and careful and atraumatic excision of the heart-lung block, procurements from as far as 1,000 miles from the transplant center and ischemic times up to 6 hours are reasonably well tolerated. The additional use of corticosteroids in the donor and white cell filtration before lung reperfusion in the recipient are also measures that contribute to improved preservation.

RECIPIENT OPERATION

The heart-lung transplant operation is composed of two phases of equal importance. The first is safe excision of the native organs with excellent hemostasis, followed by implantation of the donor organs and continued attention to excellent hemostasis.

Anesthetic monitoring includes arterial pressure, pulse oximetry, continuous electrocardiography, temperature, and urine output. A standard endotracheal tube is used, and transesophageal echocardiography may be helpful during the early stages of the operation, but should be removed during the time of recipient organ excision. This helps to prevent injury to the esophagus while dissecting in the posterior mediastinum. A median sternotomy is employed for the majority of recipients, with transverse thoracotomy (clam-shell) helpful for patients who have had extensive previous thoracotomies or pleurodesis (Fig. 64.1). In that situation, the bilateral thoracotomies offer better access to the posterior mediastinum and the apical areas of the thoracic cavity for a more meticulous dissection and better hemostasis. Otherwise, the median sternotomy is preferable for better chest wall mechanics postoperatively.

After sternotomy, both pleural spaces are opened widely just below the sternal edges. Anterior mediastinal thymic remnants and the anterior pericardium are carefully dissected and removed. The ascending aorta is dissected free and encircled with umbilical tape, followed by the superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava, as shown in Figure 64.3. Cannulation for cardiopulmonary bypass consists of a cannula in the high ascending aorta and separate vena caval cannulas, as seen in Figure 64.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree