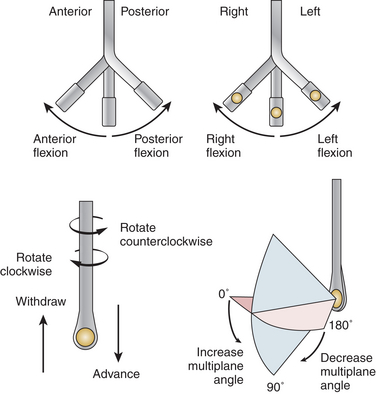

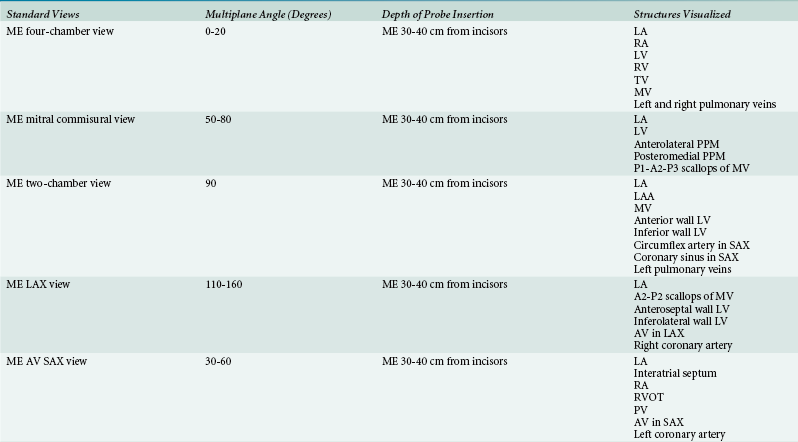

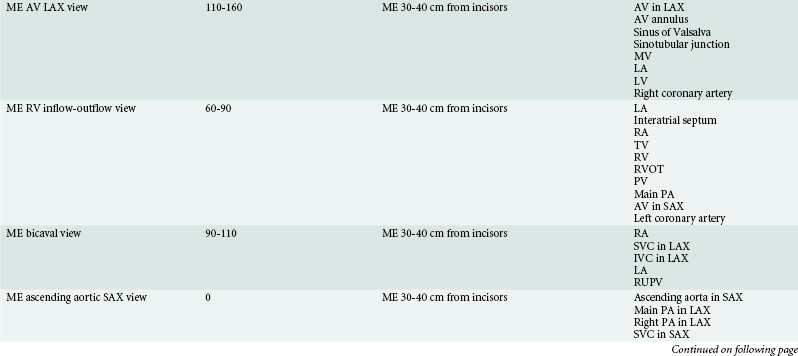

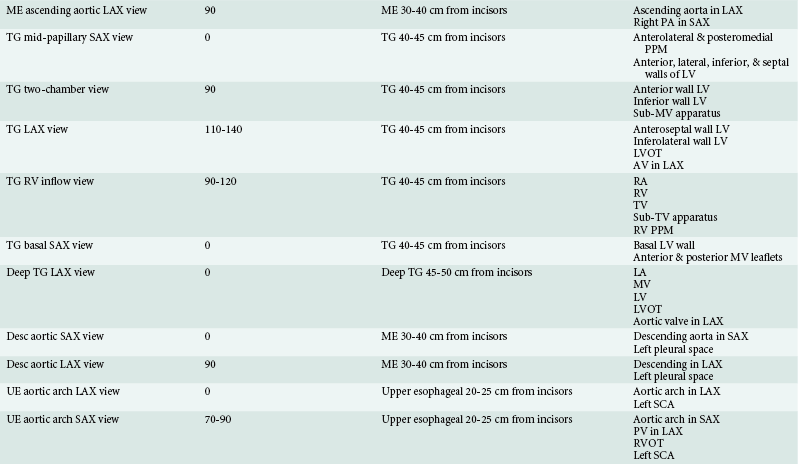

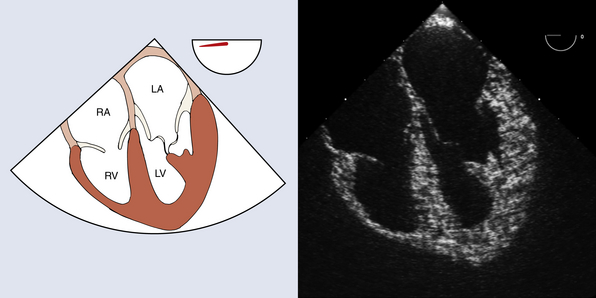

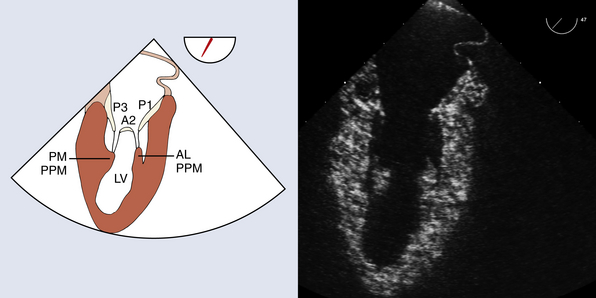

1 Sansan S. Lo, Jeremy S. Poppers, Teresa A. Mulaikal, David J. West, Michelle M. Liao and Jack S. Shanewise The clinical utility of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) has expanded since its introduction into the perioperative setting in the 1980s. TEE is a versatile tool that can be used to assess cardiac function and diagnose unanticipated problems. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists (SCA) issued guidelines for the intraoperative use of TEE in 1996 in which indications for intraoperative TEE fall under three categories. 1 Category A includes clinical scenarios for which supportive literature suggests that TEE is strongly beneficial for clinical evaluation. Examples include valve repair, congenital heart defects, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, aortic dissection, infective endocarditis, and unstable hemodynamics. Category B indications for TEE are those for which there is suggestive evidence for a benefit, and include myocardial ischemia, valve replacement, cardiac aneurysms, and intracardiac tumors. Category C indications are those for which there is equivocal literature, and include myocardial perfusion, monitoring for emboli during orthopedic procedures, and placement of intraaortic balloon pumps and pulmonary artery catheters. These guidelines were revised in 2010 and now state that in adult patients without contraindications, TEE should be used in all open (e.g., valvular) heart and thoracic aortic surgical procedures and should be considered for coronary artery bypass graft surgeries to: (1) confirm and refine the preoperative diagnosis, (2) detect new or unsuspected pathology, (3) adjust the anesthetic and surgical plan accordingly, and (4) assess the results of surgical intervention. 2 The TEE probe can be manipulated and adjusted to optimize visualization of cardiac anatomy ( Fig. 1-1). The wheels of the probe should be unlocked and in neutral position prior to movement to prevent trauma. The probe can be advanced or withdrawn within the esophagus, and the orientation of the ultrasound beam can be manipulated by rotating the probe to the patient’s left (counterclockwise) or right (clockwise). Turning the large control wheel clockwise will anteflex the probe (flex the tip anteriorly), whereas counterclockwise turning will retroflex (flex posteriorly) it. The small knob will flex the probe leftward or rightward. With a multiplane TEE probe, the transducer angle can be rotated axially from 0 (horizontal) to 90 (vertical) to 180 degrees (mirror image of 0 degrees horizontal plane) while the tip remains in a fixed position. Orienting oneself with respect to the ultrasound beam and the image displayed on the screen may be a source of confusion. An easy method often employed to orient the echocardiographer utilizes the right hand, with its thumb pointing to the left and palm facing the floor. With the patient in supine position, the operator stands at the head, facing the patient’s feet. In this position, the fingers represent the ultrasound beams as they extend perpendicularly from the head of the probe, and the thumb will point toward the left-sided structures that appear on the right side of the screen at 0 degrees. As the multiplane angle is increased to 90 degrees, the right hand is rotated clockwise until the thumb points toward the ceiling and now demonstrates anterior structures of the heart on the right side of the screen; inferior structures are displayed on the left side of the screen. In 1999 the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) and SCA published guidelines for performing a comprehensive intraoperative TEE examination that described and named 20 TEE views that comprise a complete routine examination. 3 These 20 views are summarized in Table 1-1 and described in the sections that follow. The midesophageal (ME) views ( Fig. 1-2) are typically located at a probe depth of about 30 to 40 cm from the incisors. The ME four-chamber view is often the first one that appears upon probe insertion with a multiplane angle of 0 to 20 degrees. Both atria, both ventricles, and the mitral and tricuspid valves are visualized. Much like a chest x-ray, structures on the left side of the patient appear as images on the right side of the screen and vice versa. The septal and anterior or posterior leaflets of the tricuspid valve, as well as the anterior and posterior mitral valve leaflets, are visualized in the central portion of the image sector. Either the anterior or posterior tricuspid valve leaflet appears on the left side of the image sector, depending on the degree of anteflexion. From the ME four-chamber view, the multiplane angle is rotated to 50 to 80 degrees to obtain the mitral commissural view ( Fig. 1-3). In a neutral position, the P1-A2-P3 segments of the mitral leaflets are visualized. Chordae from the anterolateral papillary muscle, which appears on the right side of the image sector, attach to P1 and the lateral side of A2. Chordae from the posteromedial papillary muscle, which appears on the left side of the image sector, attach to P3 and the medial side of A2. Figure 1-3 Midesophageal mitral commissural view. Mitral valve (P3, A2, P1 segments). AL PPM, Anterolateral papillary muscle; LV, left ventricle; PM PPM, posteromedial papillary muscle. (Two-dimensional TEE images generated using software developed by Heartworks, Inventive Medical Ltd., London, UK.)

Getting Started with Echocardiography

The Twenty Standard Views

![]() TEE: Indications, Complications, Probe Insertion, and Manipulation

TEE: Indications, Complications, Probe Insertion, and Manipulation

![]() The Twenty Standard Views

The Twenty Standard Views

Midesophageal Four-Chamber (ME Four-Chamber)

Midesophageal Mitral Commissural (ME Mitral Commissural)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine