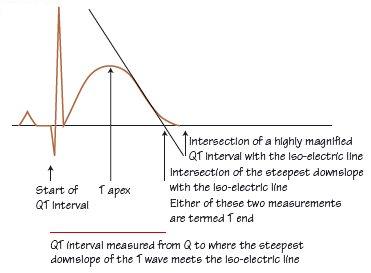

Fig. 39.2 Measurement of the QT interval. It is usual to measure the QT interval in lead II (the T wave is often very well defined). The QT interval is measured from the start of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave, where it meets the iso-electric line. The start of the QRS complex is easily determined, whereas the end of the T wave can be difficult. If difficulty is encountered, then the extrapolation of the steepest downslope of the T wave to the iso-electric line is used. Computer measurement of the QT interval is much more accurate than hand measurement; different programs measure different intervals (average QT interval across all the leads for some, in others the longest QT interval).

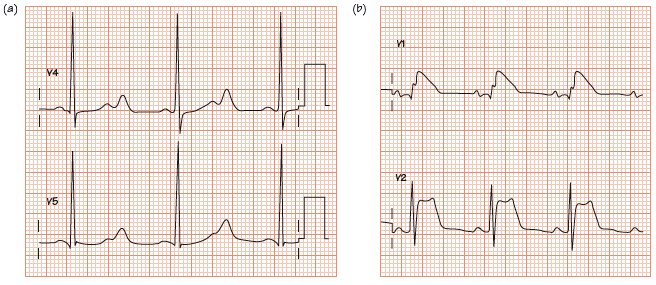

Fig. 39.3 (a) Hereditary long QT syndrome type 2 pattern ECG. Sinus rhythm, normal PR interval. QRS normal. T wave shows a late curious hump, especially lead V4. The QT interval here is 600 ms; the heart rate is 60 b/min; no heart rate correction is needed (see Chapter 17). (b) ECG from Brugada type 1. Normal P wave, PR interval, QRS complex. ST elevation in leads V1–3; lead V1 most convincing for type 1 Brugada, though T wave remains positive.

Table 1 Diagnostic criteria for the congenital long QT syndrome.*

Hereditary long QT syndrome

Hereditary long QT syndrome (HLQTS) is rare (1 in 10 000) but accounts for 50% of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in infancy and childhood. It is usually autosomal dominant (autosomal recessive genes are associated with deafness), and occurs in different forms, termed LQT1, 2, 3, etc. (Fig. 39.1a). The mechanism of death is a long-QT associated torsade-de-pointes (TDP) type ventricular tachycardia degenerating into ventricular fibrillation. The pathophysiological basis is genetic prolongation of the action potential duration (APD) leading to early after depolarizations (EADs), which underlie TDP (see Fig. 38.2). Only 60% of patients have any TDP; however, 30–40% of patients die during their first TDP event, in others TDP episodes are self-terminating until the final non-self-terminating lethal one. Eightyfive per cent of TDP episodes relate to physical/emotional stress. The untreated life expectancy is substantially reduced. Treatment (betablockers ± implantable cardioverter defibrillator [ICD]) is fairly effective. The diagnosis can be extraordinarily easy or extremely difficult, in part as 5% of affected family members have normal QT intervals! A scoring system (Table 39.1) has been suggested. However, the key to diagnosis is to measure the QT interval accurately (Fig. 39.2) and to think of the diagnosis in syncope.

Acquired long QT syndromes

Acquired long QT syndromes are common and the complicating arrhythmias (TDP) is the same as in HLQTS, emphasizing the importance of QT interval measurement in all syncope, regardless of family history:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree