Treatment strategies for symptomatic patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HC) represent an important component of the overall management armamentarium for this complex genetic disease, and have generated considerable debate in recent years. Surgical septal myectomy has been the time-honored treatment for patients with severely symptomatic obstructive HC. Myectomy has had a favorable experience extending over almost 50 years, first with the classic Morrow approach and more recently with the modified extended myectomy operation. It is generally acknowledged that septal myectomy has substantially benefited patients with HC over many decades by reliably relieving left ventricular (LV) outflow tract obstruction and normalizing LV pressures (with no or trivial residual gradients), thereby reducing or obliterating heart failure-related symptoms.

During the last 15 years, a competing percutaneous interventional technique (alcohol septal ablation) has been performed with considerable frequency, which by design produces a transmural septal infarct to reduce outflow tract gradient and symptoms. In fact, the number of alcohol ablations performed each year worldwide now easily exceeds the number of surgical myectomies. Notably, this exuberance for alcohol ablation paradoxically has increased the number of myectomy operations at referral centers, presumably by enhancing recognition of the clinical significance of outflow obstruction in HC in the practicing community, but also by demonstrating that there is an adequate volume of potential candidates for myectomy to support more expert surgeons.

We do not wish to review in detail here the vast and rapidly accumulating published works comparing myectomy and ablation, now assembled over 15 years. Furthermore, it is highly unlikely that an adequately powered randomized trial could be designed and carried out in obstructive HC to definitively resolve this issue, because of a myriad of virtually insurmountable practical problems, including the low event rate characteristic of this disease, and the necessity to screen as many as >30,000 candidates to enroll >500 suitable study patients in each arm. Nevertheless, it should be underscored that the process of comparing myectomy and ablation has in fact been vetted extensively in an unbiased fashion over the last decade—that is, first by the American College of Cardiology and European Society of Cardiology in 2003 as consensus panel recommendations and more recently in 2012 by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association as formal clinical practice guidelines.

Both expert panels reached identical positions regarding the respective indications for myectomy versus alcohol ablation. Surgery is the preferred option for most severely symptomatic drug-refractory patients with obstructive HC, whereas ablation is a selective alternative for older patients or those who are not optimal operative candidates because of associated co-morbidities, profound aversion to surgery, or particularly marked septal hypertrophy. The expert panels recognized that although each of these treatment strategies can reduce LV outflow gradient and thereby relieve symptoms, myectomy is most consistent in achieving an optimal hemodynamic and symptomatic result, and with procedural or postprocedural risks similar to (or lower than) that achieved percutaneously with alcohol ablation. With the advantage of a longer follow-up period to study the consequences of HC surgery, it is now recognized that myectomy not only leads to sustained and substantially improved quality of life but also importantly to enhanced survival equivalent to that expected in the general population.

The Problem: Factors Impeding Availability of Myectomy

These observations suggest that greater availability of myectomy would generally be advantageous to the HC patient population. However, a major factor obstructing expansion of the myectomy operation is the relative paucity of surgeons currently available with a sufficient reservoir of experience in performing this particular operation. Indeed, it is largely agreed that experience with myectomy in a sufficient number of patients is essential for the most favorable procedural outcome and that this operation is difficult to perform reliably at the highest level of expertise when undertaken only occasionally. Certainly, in this regard, the heterogenous LV outflow tract anatomy characteristic of HC requires operator experience but also creates a distinct advantage for the myectomy surgeon having direct visualization of the complex morphology, compared with interventional alcohol ablation for which the course of the first septal perforator (and therefore, the location of the septal infarct) is fixed.

Another historic obstacle to increasing the footprint of surgery in HC is the challenge of “demystifying” myectomy and conveying the “art” and technical acumen necessary to perform the operation expertly. In this regard, surgeon-to-surgeon mentorship (as described below for Mayo Clinic and Tufts) is a highly beneficial and desirable strategy. These issues are not dissimilar to the dilemma that can arise in selecting surgeons for mitral valve repair. Also, we should underscore the often-ignored issue in this myectomy versus alcohol ablation debate, that is, the importance of operator experience in performing alcohol ablation reliably with optimal hemodynamic results, and the likelihood that not all interventional laboratories are equally facile with this technique.

For many years, surgical myectomy has been confined to a few select centers in North America, for example, Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, Toronto General, Stanford, Roosevelt-St. Lukes (New York City), most recently the Tufts Medical Center (as described below), and previously the National Heart and Lung Institute (closed by the United States government [Dr. Claude Lenfant] in 1990). However, many surgical candidates cannot (or will not) choose to travel to select centers for myectomy. Therefore, although myectomy is considered the gold standard treatment for most severely symptomatic patients with HC and outflow obstruction by expert consensus panels, a referral vacuum has nevertheless been created by the relative paucity of experienced surgeons prepared to perform this operation.

Consequently, in this regard, 2 separate HC populations have evolved. Some patients with the motivation, resources, and means to travel can be referred to select centers for surgery. Many other potential operative candidates, outside of the dedicated HC centers, will by default elect the catheterization laboratory and undergo alcohol septal ablation based on local referral patterns, including some patients who may be under the misconception that septal myectomy is no longer an available treatment option.

Although alcohol ablation may be the only septal reduction procedure available at a particular institution, it may not necessarily be the preferred treatment option for each individual patient with HC. Indeed, without new surgical myectomy programs, it is inevitable that many patients eligible for the myectomy operation (the preferred treatment option) as a matter of convenience will disproportionately become candidates for the alternative therapy (alcohol septal ablation). This unique HC referral scenario is even more pronounced in Europe where septal myectomy has been virtually abandoned for about 20 years, although with some recent evidence of rejuvenation.

Notably, the views expressed here concerning the contemporary management of HC are consistent with the positions of all major cardiovascular societies (American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/European Society of Cardiology)—that is, each individual patient with HC should have access to (and the opportunity for) all appropriate treatments. When patients are presented with only 1 treatment option (e.g., alcohol ablation), they do not, in fact, have an informed choice, and the most effective way for patients to have that choice is through a program focused on HC and segregated from the general cardiology population.

A Solution: The Tufts Initiative

How can this perceived disparity in management options for patients with HC be rectified? For the septal myectomy operation to continue to flourish, it must have wider accessibility, rather than confinement to only a very few (<5) select centers and surgeons. However, truly widespread availability of myectomy is an unrealistic expectation, given that a sufficient case volume (and operating surgeons) that would be necessary to sustain multiple programs in every possible jurisdiction and venue in the Unites States is lacking. Rather, expanded access to surgery can only be achieved within cardiology divisions with formalized HC programs offering specialized disease management and all therapeutic options.

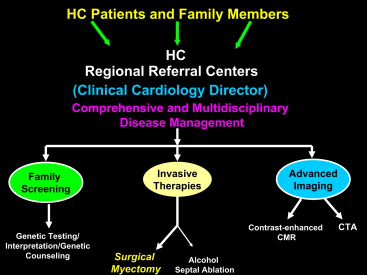

Available to patients in the setting of a formalized multidiscipline HC program are: contemporary diagnosis with advanced imaging, genetic testing, risk stratification for sudden death, the option for implantable defibrillator therapy, and importantly the possibility of expert surgical myectomy and alcohol ablation ( Figure 1 ). Furthermore, only in such referral environments can operative candidates be sufficiently clustered to accumulate the critical threshold patient volume to enable the myectomy surgeon to acquire and sustain a necessary level of expertise.

Therefore, future advancement of the myectomy operation depends on (and is intertwined with) promotion and growth of HC centers. The challenges in formulating such subspecialty programs that afford specialized disease management strategies within cardiology departments include: pre-existing barriers and entrenched referral patterns within the local practice environment, and reticence to refer patients out of the institution for surgery. Also, crucial to this concept of an HC center is an established clinical director knowledgeable in the disease, through which all patients are directed for evaluation to assure that major diagnostic and management decisions are uniform.

A prime example of a disease-specific HC program incorporating surgical myectomy was created de novo within the cardiovascular division of the Tufts Medical Center (Boston) in 2004. During 10 years, the Tufts program has enrolled and evaluated 1,300 patients with HC. During that time, Dr. Hassan Rastegar, initially mentored in the myectomy operation by Dr. Joseph Dearani (Mayo Clinic), has operated on 230 patients with obstructive HC successfully to relieve LV outflow obstruction and disabling heart failure symptoms. Operative mortality is 0.4%, consistent with the current low postoperative death rates at the largest surgical centers (Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, and Toronto General ), and largely without the morbidity associated with iatrogenic ventricular septal defect, or necessity for pacemaker implant. In addition, 95% of these patients have achieved clinical improvement postoperatively by ≥1 New York Heart Association functional class, and with 83% returned to an asymptomatic lifestyle, consistent with previous reports from older HC surgical programs.

Therefore, the experiment at Tufts serves as a model for what can be accomplished in bringing the myectomy option to patients with HC, many of whom would otherwise be excluded from that opportunity. Recently, a few other similar surgical initiatives have proved successful in Europe (e.g., Bergamo, Florence, and Milan in Italy), in addition to the long-standing program at the Thoraxcenter in Rotterdam. Furthermore, the formalized multidiscipline and specialized management approach to HC, with patients segregated within selected and experienced centers (with myectomy surgeons) as described here, is perhaps not unlike that currently being advised and promoted for transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Based on expert consensus recommendations and extensive clinical experience, surgical septal myectomy is the preferred treatment option for most severely symptomatic patients with obstructive HC. Consequently, greater availability of the myectomy operation performed by surgeons producing optimal hemodynamic and clinical results is a key element in the evolving contemporary management of HC to serve the best interests of the patient population. Novel initiatives such as the medical and surgical program at the Tufts Medical Center reported here demonstrate the potential for fulfilling the aspirations of patients with HC, and their cardiovascular specialists, to create an optimal therapeutic environment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree