28

Complications of Transesophageal Echocardiography

Introduction

Introduction

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is widely used to diagnose and monitor cardiac function. This essential imaging modality is now found in practically all cardiac surgical operating rooms, delivering pertinent information to guide surgical interventions (e.g., myocardial revascularization, valvular competence, and repair of congenital heart defects) and pharmacologic support and/or fluid administration during the perioperative period. 1 Over time, TEE’s applications have developed considerably, and its safety has been evaluated by many studies over the years; it is considered relatively safe and noninvasive. The reported risk of complications associated with TEE is 0.2% to 0.5% in the nonoperative setting, while reported mortality is 0.01%.2–5 When examining the subpopulation of cardiac surgery patients, the risk of morbidity ranges from 0.05% to 1.2%, and the risk of mortality has been reported as high as 0.02%.6–9 The goal of this chapter is to describe potential complications of TEE that can be encountered during everyday practice ( Table 28-1).

TABLE 28-1

| Site | Injury |

| Oropharynx | Dental/lip trauma, pharyngeal abrasions/hemorrhage, temporomandibular joint pain, tongue injury, hypopharyngeal perforation, tracheal intubation/vocal cord trauma |

| Esophageal | Dysphagia, odynophagia, perforation/laceration, hemorrhage |

| Gastric | Perforation/laceration, hemorrhage |

| Other | Splenic laceration, airway compromise, arrhythmias, vascular compression, burns/thermal injury, infection |

Oropharyngeal Complications

Oropharyngeal Complications

Dental trauma, pharyngeal abrasions and hemorrhage, 10 and temporomandibular joint subluxation11,12 can occur with TEE insertion. These complications can vary with blind placement versus placement under direct vision. Rigid laryngoscope–assisted insertion of the TEE probe reduces the incidence of oropharyngeal mucosal injury (55% vs. 5%), odynophagia (32.5% vs. 2.5%), and the number of insertion attempts. 13 Variations in experience and technical skill can contribute to difficulty in placement.

Insertion of the TEE probe can also be complicated by neoplasms in the oropharynx, edema or inflammatory changes, and even cervical spondylosis. 14 Difficult placement can stem from a stenotic entrance to the proximal esophagus, a Zenker diverticulum, or even hypertrophy of the cricopharyngeal muscle. 15 Other disorders, including achalasia, esophageal strictures, Schatzki rings, esophageal webs, scleroderma, and diffuse esophageal spasm can make TEE probe placement more difficult as well. Even normal anatomic variations such as a large left atrium, a large left mainstem bronchus, and esophageal cysts can hinder TEE insertion into the esophagus. 15 Double aortic arch 16 and mucosal abnormalities such as prior radiation exposure, decreased saliva production, and prior tracheostomy can also make TEE insertion more challenging. 15 These issues can lead to hypopharyngeal perforation. 17 In one series of 159 adults, optically guided TEE probe placement with transnasal videoendoscopic monitoring of the hypopharynx resulted in significantly fewer hypopharyngeal injuries than traditional blind probe placement. 18 Larger multiplane probes have also been shown to increase the difficulty of placement. 14

Increased duration of placement has also been seen to cause tongue necrosis and ischemia. The pathophysiologic mechanism of this injury includes prolonged glossal compression with venous congestion, edema, and ischemia. 19 Presence of the TEE probe may also increase the endotracheal cuff pressure more than is generally recommended. One study showed that mean intracuff pressure increased from 27.7 (±1.5) to 36.2 (±6.4) cm H2O and was over 35 cm H2O in 45% of patients. This increase in tracheal cuff pressure can be associated with reduced mucosal blood flow in the trachea and postoperative sore throat. 20

Odynophagia and Dysphagia

Odynophagia and dysphagia are the most common complaints after TEE probe placement. Some studies have reported that the incidence of swallowing dysfunction can be as high as 7.9%. Long-standing controversy exists about whether TEE is an independent risk factor for postoperative dysphagia and recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. In a study enrolling 1245 patients, 217 receiving TEE, there was no difference in the incidence of dysphagia between those who were monitored with TEE and those who were not. 21 A study enrolling 81 patients prospectively (40 patients with TEE for cardiac surgery and 41 patients without TEE for cardiac surgery) and 200 patients retrospectively (all 200 with TEE during cardiac surgery) found that the incidence of postoperative gastroesophageal symptoms were comparable in the three groups. 22 On the other hand, an examination of 869 patients noted a 4% incidence of swallowing dysfunction, and this was associated with pulmonary aspiration (90%), increased frequency of pneumonia, increased frequency of tracheostomy, and increased length of stay in the intensive care unit. 23 The incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy and concomitant dysphagia has also been attributed to TEE in some patients. However, Kawahito et al. looked at 116 patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery and concluded that placement of the TEE probe was not responsible for postoperative recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy. It was likely the surgical manipulation, duration of surgery, cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), and tracheal intubation were related to the palsy. 24 A case of intramural esophageal hematoma and odynophagia was reported in a patient undergoing atrial fibrillation ablation under general anesthesia with TEE. In this particular case, the TEE was advanced after induction of general anesthesia for evaluation of the heart and then removed. After removal of the TEE probe, there was some difficulty advancing the esophageal temperature probe, indicating a change in tissue integrity. 25 A recent study of 200 patients investigated whether modifying the TEE probe placement protocol could reduce the incidence of postoperative dysphagia. In the first group (n = 100), the TEE probe was inserted after anesthetic induction and remained in place for the duration of the surgery. In the second group (n = 100), the TEE probe was inserted after anesthetic induction and then removed after the cardiac exam. The probe was reinserted again before weaning from CPB and then immediately removed after the post-CPB examination. The incidence of dysphagia was significantly higher in patients who had the probe in place for the duration of the surgery (51.1% vs. 28.6%). Multivariate regression analysis showed that the length of time the TEE probe was in the esophagus was an independent predictor of dysphagia. 26 Although there are opposing sides to the argument over whether TEE causes postoperative dysphagia and odynophagia, it is clear that care must be taken when using or deciding to use TEE in any patient.

Esophageal Perforation

Esophageal Perforation

Esophageal perforation, a rare but life-threatening event, is the most feared complication of TEE. Studies report the risk to be anywhere from 0.01% 6 to 0.38%. 7 Many factors can predispose a patient to esophageal perforation: poor patient cooperation, inadequate technical skills of the clinician, a large calcified lymph node, 27 spasm or hypertrophy of the cricopharyngeal sphincter, cervical arthritis, forward and left lateral bending of the distal esophagus, and esophageal disease such as inflammation or neoplasm to name a few. 28 Increased risk for perforation from TEE may occur in patients with gastroesophageal pathology (Zenker diverticulum, esophageal stricture or obstructing mass, fibrosis secondary to prior chest radiation) and distorted anatomy (massive cardiomegaly, 29 tracheoesophageal fistula or atresia, and resistance to probe insertion). 30 Some authors have even suggested that small stature, longer procedures, congestive heart failure, low cardiac output prior to CPB, 31 advanced age, 32 and chronic steroid or bisphosphonate use 2 can translate into increased risk for esophageal perforation.

The site of esophageal perforation also varies. One study reported that the most common site of perforation is in the abdominal portion of the esophagus (57.3%), followed by the intrathoracic (33.3%) and cervical (9.3%) portions. 33

The mechanism of injury with the TEE probe may be multifactorial. Local pressure effects, vascular insufficiency, thermal injury, and impaired mucosal blood supply during CPB may all be involved. 7 Urbanowicz et al. studied whether the pressure produced by contact between a TEE probe and the esophagus was sufficient to cause esophageal damage. The authors concluded that the maximum surface contact pressure between the esophagus and a fully flexed TEE probe is low in dogs and in most humans and not associated with histologic esophageal damage even with prolonged exposure. They also stated that potentially dangerous pressures (>60 mmHg) could be generated in some cases in humans. The authors suggested that the TEE probe not be left in a flexed position for prolonged periods of time. 34

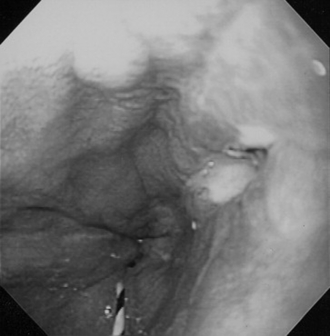

Direct trauma from placing the TEE probe (blind vs. direct visualization), advancing the probe, flexion, extension, lateral movement, and the general manipulation required to generate clearer images may also contribute to esophageal injury ( Fig. 28-1). Kharasch et al. have theorized that the vibration of the piezoelectric crystal that produces the ultrasound wave can actually heat the tip of the TEE probe itself and cause thermal injury to gastrointestinal (GI) tissues. They stated that underlying tissue ischemia may prevent dissipation of the produced heat, increasing the susceptibility to thermal injury. 35 O’Shea et al., 36 however, were unable to see any pathologic evidence of thermal injury to the esophageal mucosa in animals after prolonged CPB.

Figure 28-1 Upper endoscopy on 55-year-old man following mitral valve repair shows a medium-sized fundal hematoma. Endoscopy probe is retroflexed for the view. This hematoma was likely caused by retroflexion from TEE probe intraoperatively. GE, gastroesophageal.

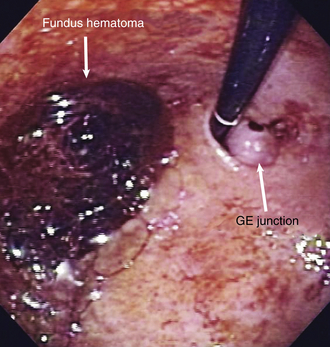

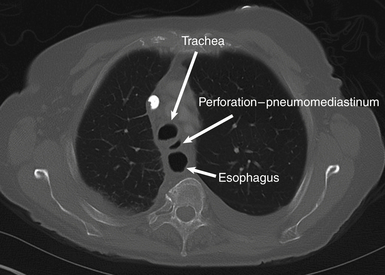

Symptoms of esophageal perforation can vary greatly from immediate and severe discomfort to delayed-onset symptoms even weeks after the time of TEE placement. The most common presentation of esophageal perforation include hemorrhage, subcutaneous emphysema, and the appearance of the TEE probe in the surgical field. Perforation can present in a much more insidious manner and can often be masked by general anesthesia during cardiac surgery. 37 Patients may present much later with nonspecific signs such as dyspnea, agitation, fever, or bloody nasogastric aspirates. Symptoms relating to spontaneous esophageal perforation, such as Meckler’s triad of vomiting, pain, and subcutaneous emphysema, are rarely present. According to one study looking at esophageal perforation from any cause, up to 33% of initial chest radiographs are within normal limits.22,30 Some studies have even suggested that late presentations were as common or more common than early presentation ( Fig. 28-2). Lennon et al. reported that in their study of 859 patients, all of the esophageal perforations (2) presented more than 48 hours after surgery (day 11 and day 4). In fact, one patient was discharged home on full anticoagulation only to return 5 days later with vague symptoms of lightheadedness and anemia. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a large amount of fresh blood in the stomach. 7 Cote et al. evaluated all reported cases of esophageal perforation after TEE procedures and found that 11/30 perforations were diagnosed more than 24 hours after surgery. 38 Esophageal perforation is associated with prolonged hospitalization and a mortality rate of 20% to 30%. 39 It is therefore imperative that clinical suspicion be high when there is any concern of perforation including post-TEE findings such as pneumothorax, pleural effusions, or postprocedural shortness of breath. 30 Diagnosis can be confirmed endoscopically or radiologically by computed tomography with contrast, upper GI barium swallow studies, and chest radiographs in the upright position ( Figs. 28-3 and 28-4). 38

Figure 28-2 Axial image from computed tomography of chest, bone window. Normal air-filled trachea and esophagus can be seen. The third focus of air between the two, which is abnormal, is likely pneumomediastinum.

Figure 28-3 Gastrografin esophagram of patient displaying a distal intrathoracic esophageal perforation. Brisk extravasation of contrast can be seen flowing over dome of left hemidiaphragm in pleural space. (From Freeman RK, van Woerkom JC, Ascioti AJ. Esophageal stent placement for the treatment of iatrogenic intrathoracic esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:2003-2008.)

Probe Mechanical Problems

Probe Mechanical Problems

Mechanical problems can occur with the TEE probe as well. There have been several reported cases of probe tip buckling in which the tip of the TEE probe folded over itself while in the esophagus, leading to difficulty in probe withdrawal. In these cases, all of the TEE operators were experienced and had an uncomplicated introduction. 40 In all reported instances, the probe could be safely removed by manipulation or pushing it into the stomach. The examiner should be wary of signs that may indicate malfunction, such as difficulty in getting images in the absence of a large diaphragmatic hernia, resistance to advancement or withdrawal of the transducer, and finding the rotary control in the maximally flexed position. 41 Inspection of the probe is mandatory, especially when using probes that have been used for more than 300 examinations. 42

Gastrointestinal Tract Bleeding

Gastrointestinal Tract Bleeding

Minor mucosal trauma during TEE can result in hematemesis or blood-tinged sputum. 41 This can be recognized from blood in the oropharynx, blood on the TEE probe upon removal from the patient, or from blood return upon suctioning of gastric contents. Norton et al. evaluated the incidence of upper GI hemorrhage in 10,573 patients. They concluded that the risk factors associated with upper GI bleeding due to TEE include previous ulcerative process, advanced age, vasoactive drugs, and failure to use H2 agonist drugs in the perioperative period. 43 Other studies have reported that extending bypass periods, emergency operations, reoperations, 44 aspirin, 6 and anticoagulant use 45 are other factors associated with an increased risk of GI bleeding.

The issue of anticoagulant use is somewhat debated. In a study of 107 patients on full anticoagulation (intravenous heparin or oral anticoagulation) for thrombotic disease or prosthetic valves, there was no increase in upper GI bleeding after TEE examination. 46 However, there is a report of a patient who underwent TEE while receiving thrombolytic therapy who developed a hemothorax following an esophageal abrasion, 47 and a patient taking Coumadin who developed a supraglottic hematoma requiring tracheostomy post TEE. 45 Although this topic is debated, it is important to take care when dealing with patients who are receiving anticoagulants and undergoing TEE.

Performing TEE on patients with known esophageal varices or undergoing liver transplantation has also been a debated topic because of the potential for esophageal hemorrhage. Spier et al. found on retrospective analysis that TEE without transgastric views can be performed without serious complications in patients with grade 1 or grade 2 esophageal varices who have not had recent hemorrhages. 48 The investigators found no major bleeding complications in any of their patients, even those with histories of prior variceal hemorrhages. This is a change from years before where many clinicians considered esophageal varices to be a contraindication to TEE. It is still prudent, however, to confirm that patients with esophageal varices have a strong clinical indication for TEE.

Other Injuries and Complications in Gastrointestinal Tract and Solid Organs

Other Injuries and Complications in Gastrointestinal Tract and Solid Organs

Intraoperative use of TEE exposes patients to ultrasound waves and pressure from the probe for prolonged periods of time. Greene et al. looked at 50 children undergoing congenital heart surgery with TEE and used flexible esophagoscopy to evaluate their esophagus after removal of the TEE probe. 49 Some 64% (32 of 50) had abnormal results on esophageal examinations (i.e., hematoma, mucosal erosion, and petechiae). It was noted that 20 of the 25 smaller patients (80%) had abnormal results compared with 12 of the 25 larger patients (48%). It has been reported that powerful ultrasound beams (pressure of 1 MPa) can cause vibration of gas-filled structures, leading to hemorrhage and hemolysis. 50 These beams can also produce excessive heat, cavitation, and the ultrasonic activation of gas bodies; this includes the potentially violent collapse of small gas bodies in or near tissue. 51 TEE probes available for clinical use have much lower intensity (≈5 MHz) and are unlikely to cause hemorrhage or harmful side effects. Pressures of up to 60 mmHg generated from the position of the probe (e.g., flexing against the esophagus) can lead to intramural hemorrhage or mucosal tears. It has been suggested that the probe should not be left in the flexed position for extended periods of time. 52

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree