Chronic Pulmonary Thromboembolism and Pulmonary Thromboendarterectomy

Michael M. Madani

Stuart W. Jamieson

Pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE) for the treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is an uncommon surgical procedure; however, it is the only curative option that provides immediate and permanent cure for this devastating disease. The condition is remarkably underdiagnosed, and as a result the procedure is uncommonly applied. Patients with chronic pulmonary hypertension secondary to thromboembolic disease may present with a variety of debilitating cardiopulmonary symptoms. However, once it is diagnosed, there is no curative role for medical management, and surgical removal of the thromboembolic material is the only therapeutic option.

The exact incidence of pulmonary embolism (PE) is unknown, but there are some valid estimates. Acute PE is the third most common cause of death (after heart disease and cancer). Approximately, 75% of autopsy-proven PEs are not detected clinically. It is estimated that PE results in approximately 700,000 symptomatic episodes in the United States yearly. The disease is particularly common in hospitalized elderly patients. Of the hospitalized patients who develop PE, 12% to 21% will die in the hospital, and another 24% to 39% die within 12 months. Thus, approximately 36% to 60% of the patients who survive the initial episode live beyond 12 months, and they may present later in life with a wide variety of symptoms.

The mainstay of treatment of patients with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and acute PE is medical management. In general, cardiac surgeons rarely intervene in hospitalized patients who suffer a massive embolus that causes life-threatening acute right heart failure and severe hemodynamic compromise. In contrast, the only treatment for patients with chronic pulmonary thromboembolic disease is the surgical removal of the disease by means of PTE. Medical management in these patients is only palliative, and surgery by means of transplantation is an inappropriate use of resources with less than satisfactory results.

The prognosis for patients with pulmonary hypertension is poor, and it is worse for those who do not have intracardiac shunts, since the shunt will reduce right-sided pressures. Thus, patients with primary pulmonary hypertension and those with pulmonary hypertension secondary to pulmonary emboli fall into a higher risk category than those with Eisenmenger syndrome and have a higher mortality rate. In fact, once the mean pulmonary pressure in patients with thromboembolic disease reaches ≥50 mmHg, the 3-year mortality approaches 90%.

Surgical preferences are dependent on both the principal disease process and the reversibility of the pulmonary hypertension. With the exception of thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, lung transplantation is the only effective therapy for patients with end-stage pulmonary hypertension. Although it has been performed less frequently in the last few years, pulmonary transplantation is still used in some centers as the treatment of choice for patients with thromboembolic disease. However, a true assessment of the effectiveness of any therapy should take into account the total mortality after the patient has been accepted and put on the waiting list. Thus, the mortality for transplantation (and especially double-lung or heart-lung transplantation) as a therapeutic strategy is much higher than is generally appreciated because of the significant loss of patients awaiting donors. Bearing in mind, in addition, the long-term use of immunosuppressants with their associated side effects, the higher operative morbidity and mortality, the inferior prognosis even after successful transplantation, and the long waiting period, one can see that transplantation is clearly an inferior alternative to PTE and should be considered an inappropriate and outdated form of therapy.

INCIDENCE

Determining an accurate incidence of CTEPH is almost impracticable. Most patients with this condition do not have a clear history of DVT or PE. Furthermore, the majority (about 75%) of autopsy-proven PEs are not clinically diagnosed. This makes the exact incidence of this disease even more difficult to determine than that of acute PE. A conservative estimate only considers patients who do have an acute PE and survive the episode. There are approximately 600,000 such patients every year in the United States. The incidence of chronic thrombotic occlusion in the population depends on what proportion of patients fails to resolve acute embolic material. Recent studies have shown that of these patients, up to 3.1% will have symptomatic CTEPH at 1 year and 3.8% will have it at 2 years. If these figures are correct, and if one counts only patients with symptomatic acute pulmonary emboli, approximately 18,000 to 22,000 individuals would progress to CTEPH in the United States each year. However, because many (if not most) patients diagnosed with chronic thromboembolic disease have no antecedent history of acute embolism, the true incidence of this disorder must be much higher.

Regardless of the exact incidence or the circumstances, it is clear that both acute embolism and its chronic relation, fixed chronic thromboembolic occlusive disease, are much more common than generally appreciated and are seriously underdiagnosed. Calculations extrapolated from mortality rates and the random incidence of major thrombotic occlusion found at autopsy support a postulate that more than 100,000 people in the United States currently have pulmonary hypertension that could be relieved by operation.

PATHOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Most cases of chronic pulmonary emboli arise from previous acute embolic episodes, even though the majority of individuals with chronic pulmonary thromboembolic disease are unaware of a past thromboembolic event and give no history of deep venous thrombosis. Why some patients have unresolved emboli is not certain, but a variety of factors must play a role, alone or in combination.

For instance, the volume of acute embolic material may simply overwhelm the lytic mechanisms, and the total occlusion of a major arterial branch may prevent lytic material from reaching, and therefore dissolving, the embolus completely. Furthermore, repetitive emboli may not be able to be resolved. Other causes may relate to the fact that the emboli may be made of substances that cannot be resolved by normal mechanisms (already well-organized fibrous thrombus, fat, or tumor), and the lytic mechanisms themselves may be abnormal. In some groups, patients may actually have a propensity for thrombus or a hypercoagulable state.

In general, after the clot becomes wedged in the pulmonary artery, one of two processes occurs: (1) the clot may proceed to canalization, producing multiple small endothelialized channels separated by fibrous septa (i.e., bands and webs) or (2) it may continue to form a solid mass of dense, fibrous connective tissue, without canalization, totally obstructing the arterial lumen.

In addition, chronic indwelling central venous catheters and pacemaker leads are sometimes associated with pulmonary emboli. Less frequent causes include tumor emboli; tumor fragments from stomach, breast, and kidney malignancies have been demonstrated to cause chronic pulmonary arterial occlusion. Right atrial myxomas may also fragment and embolize.

Whatever the predisposing factors to residual thrombus within the vessels, the genesis of the resultant pulmonary vascular hypertension is more complex than generally appreciated. With the passage of time, the increased pressure and flow as a result of redirected pulmonary blood flow in the previously normal pulmonary vascular bed can create a vasculopathy in the small precapillary blood vessels similar to the Eisenmenger syndrome.

Factors other than the simple hemodynamic consequences of redirected blood flow are also probably involved in this process. For example, after a pneumonectomy, 100% of the right ventricular output flows to one lung, yet little increase in pulmonary pressure occurs, even with follow-up to more than a decade. In patients with thromboembolic disease, however, we frequently detect pulmonary hypertension even when <50% of the vascular bed is occluded by thrombus, and not uncommonly as early as a few months to 1 year after the initial episode. It thus appears that an array of sympathetic neural connections and hormonal changes may be responsible for setting off pulmonary hypertension in the initially unaffected pulmonary vascular bed. This process can occur with the initial occlusion in either the same or the contralateral lung.

Regardless of the cause, the evolution of pulmonary hypertension as a result of changes in the previously unobstructed bed is serious because this process may lead to an inoperable situation. Accordingly, with our accumulating experience in patients with thrombotic pulmonary hypertension and superior surgical outcomes, we have increasingly been inclined toward early operation so as to avoid these changes.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

CLINICAL PRESENTATIONThere are no specific signs or symptoms associated with pulmonary hypertension as a result of chronic pulmonary thromboembolism, which explains the degree of underdiagnosis with this condition. The most common symptom associated with thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, as with all other causes of pulmonary hypertension, is exertional dyspnea. Generally, this dyspnea is out of proportion to any abnormalities found on clinical examination. Like complaints of easy fatigability, dyspnea that initially occurs only with exertion is often attributed to anxiety or being “out of shape.” In patients with more advanced disease and higher pulmonary artery pressures, syncope or presyncope (lightheadedness during exertion) is another common symptom.

Nonspecific chest pains occur in approximately 50% of patients with more severe pulmonary hypertension. Hemoptysis can occur in all forms of pulmonary hypertension and probably results from abnormally dilated vessels distended by increased intravascular pressures. Peripheral edema, early satiety, and epigastric or right upper quadrant fullness or discomfort may develop as the right heart fails (cor pulmonale). Some patients with chronic pulmonary thromboembolic disease present after an additional small acute pulmonary embolus that may produce acute symptoms of right heart failure. A careful history will bring out symptoms of dyspnea on minimal exertion, easy fatigability, diminishing activities, and episodes of angina-like pain or lightheadedness. Further examination reveals the signs of pulmonary hypertension.

The physical signs of pulmonary hypertension are the same no matter what the underlying pathophysiology. Initially, the jugular venous pulse is characterized by a large A wave. As the right heart fails, the V wave becomes predominant. The right ventricle is usually palpable near the lower left sternal border, and pulmonary valve closure may be audible in the second intercostal space. Occasional patients with advanced disease are hypoxic and slightly cyanotic. Clubbing is an uncommon finding.

As the right heart fails, a right atrial gallop is usually present, and tricuspid insufficiency develops. Because of the large pressure gradient across the tricuspid valve in pulmonary hypertension, the murmur is high pitched and may not exhibit respiratory variation. These findings are quite different from those usually observed in tricuspid valvular disease. A murmur of pulmonic regurgitation may also be detected.

DIAGNOSIS

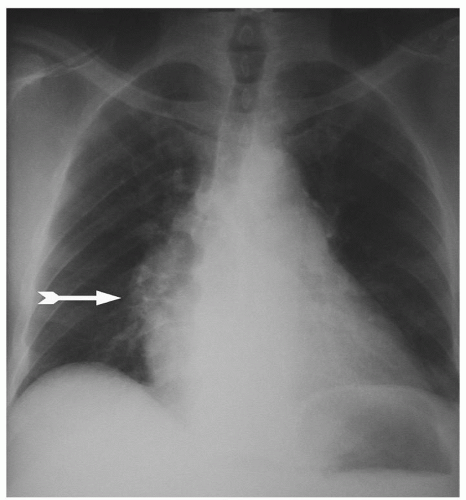

DIAGNOSISTo ensure the diagnosis in patients with chronic pulmonary thromboembolism, a standardized evaluation is recommended for all patients who present with unexplained pulmonary hypertension. This workup includes a chest radiograph, although a large number of patients present with a relatively normal chest radiograph, even in the setting of high degrees of pulmonary hypertension. When abnormal, the chest X-ray may show either apparent vessel cutoffs of the lobar or segmental pulmonary arteries, or regions of oligemia suggesting vascular occlusion. Central pulmonary arteries are also typically enlarged, and the right ventricle may be enlarged without enlargement of the left atrium or ventricle (Fig. 70.1).

The ventilation-perfusion lung scan is the essential test for establishing the diagnosis of unresolved pulmonary thromboembolism. An entirely normal lung scan excludes the diagnosis of both acute and chronic, unresolved thromboembolism. The usual lung scan pattern in most patients with pulmonary hypertension is either relatively normal or shows a diffuse nonuni-form perfusion. When subsegmental or larger perfusion defects are noted on the scan, even when matched with ventilatory defects, pulmonary angiography is appropriate to confirm or rule out thromboembolic disease.

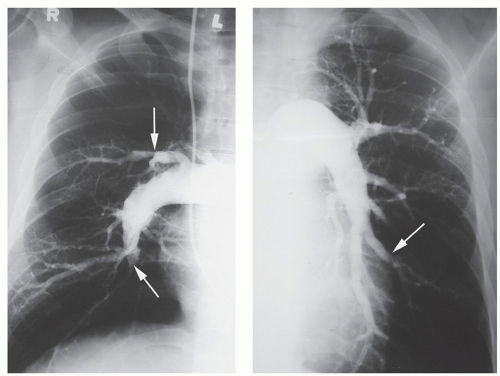

Pulmonary angiography is the gold standard for the diagnosis of chronic pulmonary thromboembolism. In addition to identifying the level of obstruction and providing a surgical roadmap, right heart catheterization can be performed in the same setting, measuring right heart parameters and evaluating the degree of pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). Organized thromboembolic lesions do not have the appearance of the intravascular filling defects seen with acute pulmonary emboli, and experience is essential for the proper interpretation of pulmonary angiograms in patients with unresolved, chronic embolic disease. Typically, organized thrombi appear as unusual filling defects, webs, or bands or as completely thrombosed vessels that may resemble congenital absence of the vessel (Fig. 70.2). Organized material along a vascular wall of a recanalized vessel produces a scalloped or serrated luminal edge. Because of both vessel-wall thickening and dilation of proximal vessels, the contrast-filled lumen may appear relatively normal in diameter. Distal vessels demonstrate the rapid tapering and pruning characteristic of pulmonary hypertension.

In recent years, higher resolution computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest have been used more frequently in the diagnosis of PE. The presence of large clots in lobar or segmental vessels generally confirms the diagnosis. In addition, in rare situations where occlusion of main pulmonary arteries is present or there are concerns of external compression, CT scans can be helpful to differentiate thromboembolic disease from other causes of pulmonary vascular obstruction such as mediastinal fibrosis, lymph nodes, and tumors. CT scanning has the disadvantage, however, that it may miss distal disease.

Fig. 70.2. Right and left pulmonary angiograms demonstrate intraluminal filling defects, abrupt cutoffs of branches, and bands (white arrows). Note lack of filling to the periphery. |

Pulmonary angiography remains the gold standard for the diagnosis and for planning the operative approach. In addition to pulmonary angiography, patients older than 45 years of age undergo coronary arteriography and other cardiac investigation as necessary. If significant disease is found, additional cardiac surgery is performed at the time of PTE.

Pulmonary angioscopy may be performed in patients where the differentiation between the primary pulmonary hypertension and distal small-vessel pulmonary thromboembolic disease is difficult. The pulmonary angioscope is a fiberoptic telescope that is placed through a central line into the pulmonary artery. The tip contains a balloon that is then filled with saline and pushed against the vessel wall. A bloodless field can thus be obtained to view the pulmonary artery wall. The classic appearance of chronic pulmonary thromboembolic disease by angioscopy consists of intimal thickening, with intimal irregularity and scarring, and webs across small vessels. The presence of embolic disease, occlusion of vessels, or thrombotic material is diagnostic.

ALTERNATIVE TREATMENTS

Medical therapy for CTEPH is of limited value and is palliative at best. There are a wide variety of pharmacologic agents in recent use for the treatment of primary pulmonary hypertension. These include calcium-channel blockers such as diltiazem and nifedipine, prostacyclins such as epoprostenol (Flolan, Remodulin), prostacyclin analogs, endothelin-receptor antagonists (Tracleer), and nitric oxide. However, thromboembolic disease represents a mechanical obstruction that is not amenable to drug therapy.

Right ventricular failure is generally treated with diuretics and vasodilators, and although some improvement may result, the effect is generally transient because the failure will not resolve until the obstruction is removed. Similarly, the prognosis is unaffected by medical therapy, which should be regarded as only supportive. However, because of the bronchial circulation, pulmonary embolization seldom results in tissue necrosis. Surgical endarterectomy, therefore, will allow distal pulmonary tissue to be used once more in gas exchange.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree