Fig. 5.1

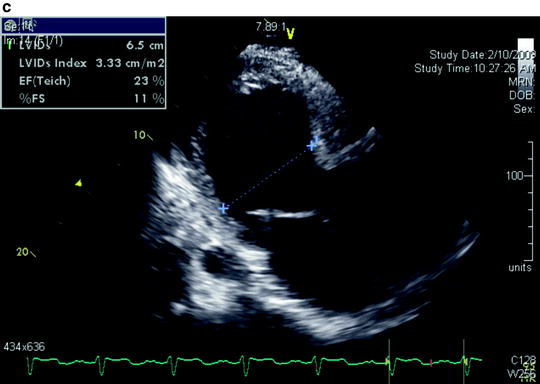

(a) Parasternal long-axis view with color flow imaging by transthoracic echocardiography shows severe aortic insufficiency. (b) Parasternal long-axis view shows severe annuloaortic ectasia causing poor coaptation of the aortic valve leaflets. (c) Parasternal long-axis view shows severe left ventricular dilatation and poor ejection fraction resulting from long-standing severe aortic insufficiency

Fig. 5.2

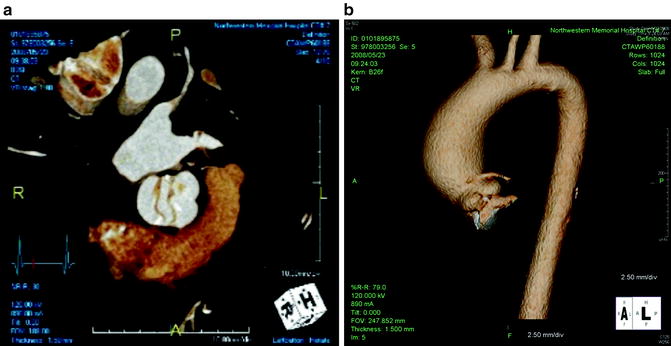

(a) Echocardiogram (ECG)-gated dual-source computer tomography with 3-dimensional reconstruction shows an aortic valve with bicuspid morphology. (b) ECG-gated dual-source computer tomography with 3-dimensional reconstruction shows an associated ascending aortic aneurysm

When symptoms from severe AI are mild, LV dilatation can become severe with left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) >70 mm and left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD) >50 mm due to chronic volume overload of the LV (Fig. 5.3). Severe LV dysfunction, particularly with ejection fraction (EF) less than 25 %, may be irreversible. Whereas patients that undergo aortic valve replacement (AVR) before the development of advanced heart failure can expect a reduction in LV dimensions in the first several months after surgery and subsequent long-term improvement in EF [1], patients with advanced heart failure may not realize such improvement even after successful correction of the AI with AVR [2].

Fig. 5.3

Left ventricular dilatation resulting from chronic aortic insufficiency (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 1999–2013)

Prognosis of Aortic Insufficiency with Heart Failure

Patients who develop acute, severe AI, most commonly from an acute type A aortic dissection or infective endocarditis, have a life-threatening condition as the LV cannot compensate for the abrupt onset of volume overload. Because patients with acute severe AI often present with LV deterioration, manifested by pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock, urgent treatment is necessary. Intensive vasodilator therapy is beneficial when feasible, but urgent surgical intervention is required.

Patients with chronic AI, however, can tolerate the gradual onset of volume overload with compensatory eccentric hypertrophy of the LV. Asymptomatic patients with severe AI and normal LV function have a risk of sudden death of less that 0.2 % per year. However, the natural history of symptomatic patients with severe AI is poor with a risk of death greater than 10 % per year for patients with angina pectoris and greater than 20 % per year for patients with heart failure [3–5]. Studies in animals shows that long-standing chronic AI results in myocardial fibrosis with increased deposition of extracellular matrix [6]. The resulting myocardial fibrosis may be the pathologic basis of irreversible LV dysfunction and end-stage heart failure for patients with severe AI.

Historical Results of Aortic Valve Replacement for Aortic Insufficiency

AVR for patients with AI and advanced heart failure (EF <25 %) can be associated with an operative mortality of up to 10 % and poor long-term survival [7]. Because of such poor outcomes, consideration of heart transplantation for these patients has been recommended in the past. However, results of AVR for AI with advanced heart failure (EF <30 %) have improved dramatically over time with operative mortality of 17 % before 1985 compared to 0 % after 1985 in a large surgical series (Fig. 5.4) [8]. Moreover, patients with advanced heart failure undergoing AVR after 1985 can have a long-term survival similar to patients without advanced heart failure (Fig. 5.5).

Fig. 5.4

Improved operative mortality after aortic valve replacement for patients with chronic aortic insufficiency and advanced heart failure over time (Reprinted from Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Vol. 49, Bhudia SK, McCarthy PM, Kumpati GS, Helou J, Hoercher KJ, Rajeswaran J, Blackstone EH, Improved outcomes after aortic valve surgery for chronic aortic regurgitation with severe left ventricular dysfunction, pages 1465–1471, copyright 2007, with permission from Elsevier)

Fig. 5.5

Long-term survival of patients undergoing aortic valve replacement after 1985 for patients with ejection fraction <30 % is similar to that for patients with ejection fraction >30 % (Reprinted from Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Vol. 49, Bhudia SK, McCarthy PM, Kumpati GS, Helou J, Hoercher KJ, Rajeswaran J, Blackstone EH, Improved outcomes after aortic valve surgery for chronic aortic regurgitation with severe left ventricular dysfunction, pages 1465–1471, copyright 2007, with permission from Elsevier)

Current Recommendation for AVR for AI and HF

Recommendation from the 2008 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) and 2007 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for chronic AI are similar [7, 9]. Class I indications for surgery for patients with severe AI include the presence of symptoms, LV dysfunction with EF <50 %. Class IIa indications include LV dilatation with LVESD >55 mm or LVEDD >75 mm and concomitant cardiac surgery including coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), other valvular surgery, or aortic aneurysm repair. Class IIb indications include LV dilatation with LVESD >50 mm or LVEDD >70 mm. No particular recommendations are made by either set of guidelines regarding patients with advanced heart failure. Although patients with recent onset of symptoms and patients that improve with intensive medical therapy including intensive vasodilators, diuretics, or inotropic support may demonstrate LV recovery after AVR, exactly which patients will demonstrate an improvement in LV function after a successful AVR is unknown. AVR is, nevertheless, a better alternative than the higher risk of long-term medical management alone for severe AI with advanced heart failure [10]. Therefore, it is reasonable to proceed with AVR in patients with severe AI and advanced heart failure in order to stop further decompensation and facilitate the chronic medical management of the patient’s heart failure, especially the use of beta-blockers which is contraindicated in patients with AI. If possible, the use of blood transfusion should be avoided in patients with advanced heart disease in case further deterioration occurs, resulting in candidacy for heart transplantation.

Aortic Stenosis and Heart Failure

Aortic stenosis can be caused by senile, calcific aortic stenosis, which is the most common cause for patients older the 75 years; bicuspid aortic valve, which commonly manifest in younger patients between 65 and 75 years; or, less frequently, rheumatic heart disease. The diagnosis of severe aortic stenosis is made with echocardiography based on a combination of parameters. Peak jet velocity and mean pressure gradients can be reliably measured but are flow dependent and therefore affected by the left ventricular stroke volume and cardiac output. Aortic valve area, calculated using the continuity equation, is less dependent on stroke volume and cardiac output and most reliably identifies patients with severe AS in advanced heart failure. When peak jet velocity >4.0 m/s, mean valvular gradient >40 mmHg, or aortic valve area <1.0 cm2, the AS is considered severe [7].

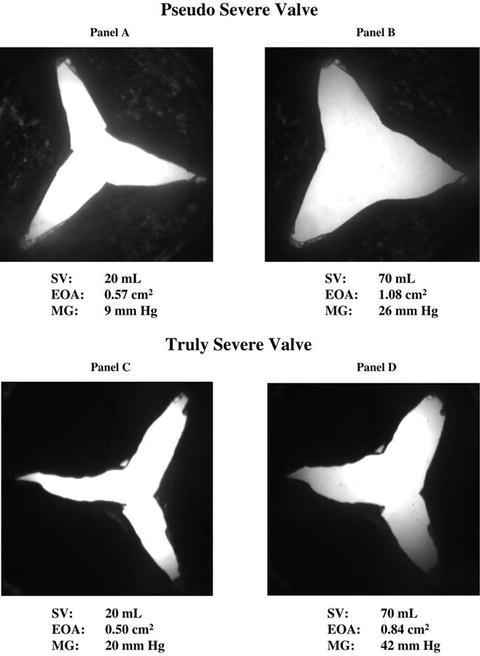

In advanced heart failure, the left ventricle is unable to generate either a significant peak jet velocity or mean pressure gradient despite an aortic valve area that is diagnostic for severe aortic stenosis. This condition, termed low-gradient aortic stenosis (LGAS), can present a diagnostic challenge for clinicians because patients with LGAS can have either truly severe aortic stenosis with resulting poor ejection fraction or primary cardiomyopathy with only moderate aortic stenosis. The latter condition, termed pseudo-severe AS, occurs because the calculated aortic valve area may not be a reliable measurement of the severity of AS. In advanced heart failure, the aortic valve may fail to open completely not as a result of a fixed stenosis but as a result of low stroke volume (Fig. 5.6). Patients with pseudo-severe AS, therefore, have a calculated aortic valve area which is falsely reduced.

Fig. 5.6

In vitro comparison of fixed severe aortic stenosis with pseudo-severe aortic stenosis. (Reprinted with permission from Blais C, Burwash IG, Mundigler G, Dumesnil JG, Loho N, Rader F, Baumgartner H, Beanlands RS, Chayer B, Kadem L, Garcia D, Durand L-G, Pibarot P. Projected valve area at normal flow rate improves the assessment of stenosis severity in patients with low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis: the multicenter TOPAS (Truly or Pseudo-Severe Aortic Stenosis) study. Circulation. 2006;113(5):711–721)

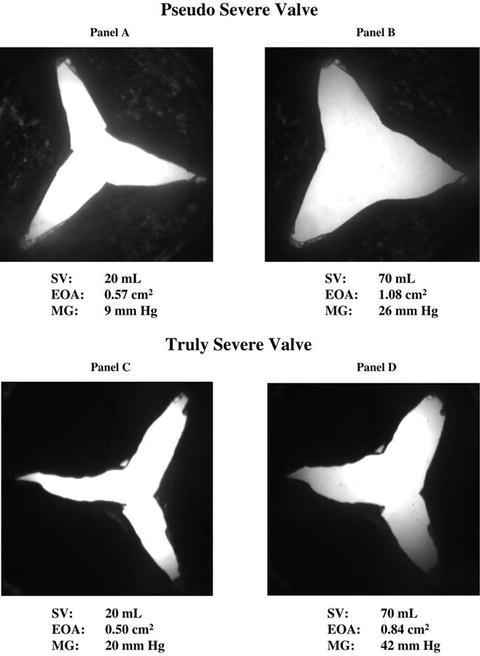

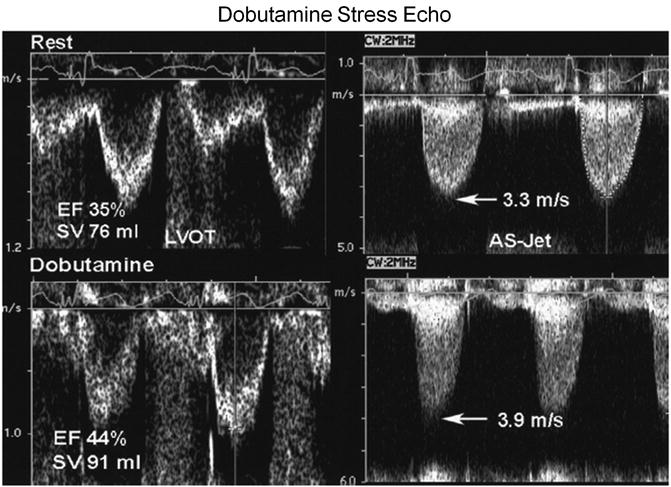

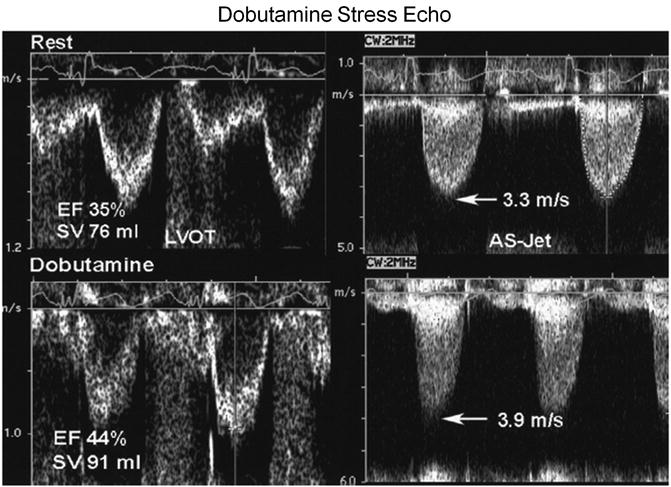

In order to distinguish between fixed severe AS and pseudo-severe AS, a dobutamine stress study either with echocardiography (Fig. 5.7) or direct pressure measurements during cardiac catheterization (Fig. 5.8) can be performed in patients with LGAS. Doses of up to 20 mcg/kg/min of dobutamine are infused under physician surveillance, while the peak jet velocity, mean pressure gradient, and aortic valve area are measured. In patients with fixed aortic stenosis, the peak jet velocity and mean pressure gradient will increase while the valve area remains unchanged as stroke volume and ejection fraction increases. In patients with pseudo-severe AS, on the other hand, the valve area increases while the peak jet velocity and mean pressure gradient remain unchanged [11, 12].

Fig. 5.7

Dobutamine stress echocardiography demonstrates the difference in response in patients with fixed aortic stenosis and pseudo-severe aortic stenosis (Reprinted from Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Vol. 47, Otto CM, Valvular aortic stenosis: disease severity and timing of intervention, pages 2141–2151, copyright 2006, with permission from Elsevier)

Fig. 5.8

Response to dobutamine during cardiac catheterization demonstrates the hemodynamic changes in patients with fixed aortic stenosis, pseudo-severe aortic stenosis, and no contractile reserve (Reprinted with permission from Nishimura RA, Grantham JA, Connolly HM, Schaff HV, Higano ST, Holmes DR Jr. Low-output, low-gradient aortic stenosis in patients with depressed left ventricular systolic function: the clinical utility of the dobutamine challenge in the catheterization laboratory. Circulation. 2002;106(7):809–813)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree