Anomalies of Systemic Venous Drainage

Sanjiv K. Gandhi

Ralph D. Siewers

INTRODUCTION

This chapter discusses the abnormalities of position and connection of the major systemic venous channels that drain into the heart. Although an understanding of the morphogenesis of the venous system is important, a classification of venous anomalies that is helpful to the surgeon is most appropriately based on anatomic considerations. Thus, this chapter is organized on an anatomic basis, and the anomalies of the venous system within each anatomic segment are addressed. Few of these venous anomalies are intrinsically pathologic to the circulation. However, many, if not most, present important surgical considerations during the palliation or correction of congenital cardiac conditions. Diagnosis of these abnormal systemic venous connections can usually be made echocardiographically, although angiography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging serve as adjunctive and very useful modalities.

Where appropriate, the relative frequency of presentation and incidence of the major venous anomalies is provided. This incidence is based on the Cardiology Patient Database at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh (CHP), which numbers >34,200 patients entered from 1955 to 1979. The information is based on a diligent coding of all cardiovascular anomalies in this patient database. Further information from the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh Heart Museum database is also used when appropriate to illustrate certain relationships between classes of congenital heart defects and anomalies of the systemic venous circulation.

ANOMALIES OF THE SUPERIOR CAVAL VEINS

Bilateral Superior Caval Veins Draining to the Systemic Venous Atrium

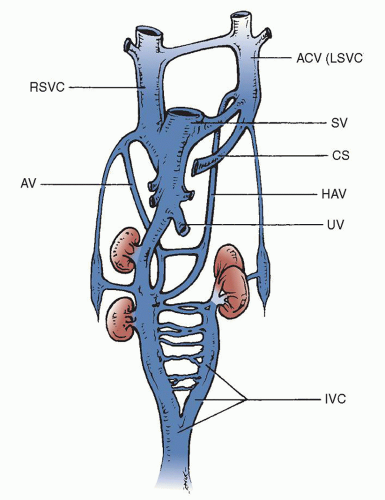

The superior caval drainage embryologically begins by means of paired cardinal veins (Fig. 76.1). After development of the left brachiocephalic (innominate) vein at week 7 of gestation, the left superior vena cava (SVC) usually involutes and becomes the ligament of Marshall. The most common anomaly of the superior caval circulation is persistence of the left SVC. This is readily recognized during cardiac catheterization or echocardiography and is frequently seen with the absence of the left innominate vein. Small bridging veins between the right and left SVCs may be present, thus joining the superior cavae. The presence of a left SVC may cause the right SVC to be somewhat smaller than usual, but the relative size of either the right or left vein is variable. In the usual circumstance, with rare exception, if there are no lateralization abnormalities, the left SVC drains into the coronary sinus and thus into the systemic or morphologic right atrium. It produces no physiologic abnormalities in its isolated condition and only becomes important when it is associated with other cardiac anomalies that require surgical correction or during cardiac transplantation.

The presence of bilateral SVCs, with the left caval vein entering the coronary sinus, is by far the most common major venous anomaly in the CHP database. It was found in 0.8% of all the patients and in >4% of the specimens in the heart museum. Seventeen percent of these patients had ventricular septal defects, and 10% to 15% had coarctation of the aorta, tetralogy of Fallot, or atrioventricular septal defects. A slightly smaller percentage had atrial septal defects, double-outlet right ventricle, transposition of the great vessels, and various forms of single-ventricle anatomy.

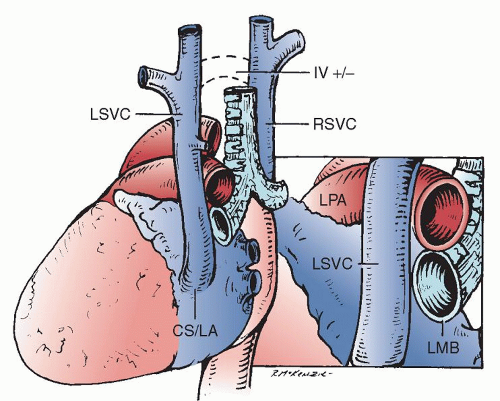

The left SVC originates at the junction of the left jugular and left subclavian veins. It is located anterior to the aortic arch and left pulmonary artery. Before entering the pericardial space, it accepts the hemiazygos vein, then runs inferiorly and medially into the posterior atrioventricular groove and joins the coronary sinus passing between the left pulmonary veins and the left atrial appendage (Fig. 76.2).

When the right atrium must be opened during open cardiac surgical procedures, provision must be made for management of both right and left SVC drainage. Short periods of occlusion of one, either the right or the left SVC, are tolerated nicely, but long procedures usually require cannulation of not only the right superior vein but also the left. It is believed that venous pressures proximally in the left SVC system that are <30 mmHg when the left SVC is occluded are well tolerated during most surgical procedures.

There are several options for managing drainage of the left SVC. This may be managed by cannulation through the coronary sinus from within the right atrium or directly with surgical cannulation of the left SVC using techniques similar to those on the right side. In very small infants, the use of circulatory arrest is another potential option. Bilateral SVCs, when joined by a bridging vein reminiscent of the left innominate vein, allow for the usual right SVC cannulation and simple (temporary) occlusion of the left SVC. The presence or absence of a left innominate vein is readily determined early during the operation when a midsternal approach is taken.

The augmented blood flow through the coronary sinus enlarges the coronary sinus, and this becomes an important echocardiographic manifestation of the presence of a left SVC that drains via the coronary sinus. Knowledge that a left SVC is present in the face of a coronary sinus orifice that appears normal is a tip that the left SVC may drain directly into the left atrium or that the coronary sinus may be “unroofed.” An enlarged or dilated coronary sinus is an important consideration during the surgical repair of specific heart defects, the most important one perhaps being the repair of an atrioventricular septal defect. In this abnormality, which was present in 15% of our patients with a left SVC draining into the coronary sinus, the large and dilated coronary sinus changes somewhat the anatomic relationships during the surgical repair. In some centers, the placement of the septal

patch, because of concern over conduction system injury, will leave the coronary sinus orifice on the pulmonary venous side of the reconstructed atrial septum. This, of course, would not be acceptable with a left SVC draining via the coronary sinus, resulting in a significant right-to-left shunt, unless the SVC could be moved or perhaps closed if bridging veins to the right SVC were present.

patch, because of concern over conduction system injury, will leave the coronary sinus orifice on the pulmonary venous side of the reconstructed atrial septum. This, of course, would not be acceptable with a left SVC draining via the coronary sinus, resulting in a significant right-to-left shunt, unless the SVC could be moved or perhaps closed if bridging veins to the right SVC were present.

Another rare problem can then be encountered with a left SVC entering the coronary sinus in patients who have elevations of right atrial pressure and pulmonary hypertension in the presence of a dilated coronary sinus, which can impinge on the wall of the left atrium and create what appears echocardiographically and functionally to be a cor triatriatum with limitation of free flow from the pulmonary venous confluence across the mitral valve. The coronary sinus, when decompressed on bypass with the heart under cardioplegic arrest, eliminates the ridge seen on echocardiography, and the defect can be quite obscure.

Although persistence of the left SVC, which drains through an intact coronary sinus into the right atrium, is not intrinsically a pathologic state, a defect in the common wall between the coronary sinus and the left atrium will produce a variable degree of interatrial communication and often must be surgically repaired. These defects in the partition may be small and relatively minor and become of greater significance only in association with complex disease. However, almost complete absence of this partition causes mixing and bidirectional shunting at the atrial level with the resultant systemic desaturation. It is difficult to diagnose various forms of unroofing of the coronary sinus when in association with a persistent left SVC. However, during the surgical repair of interatrial septal defects and other lesions in association with the persistence of the left SVC, the integrity of the coronary sinus with its drainage into the right atrium should be ascertained. Surgical options may include ligation of the SVC if a left innominate vein is present, and then a repair of the coronary sinus interatrial communication in the usual way, or simply a patching of the coronary sinus/left atrial defect to maintain left superior caval drainage into the right atrium through the coronary sinus. This condition is discussed in detail in a later chapter.

Isolated Left Superior Caval Vein

The presence of a left SVC may rarely be associated with the absence of the right SVC. When this occurs, there is a right brachiocephalic (innominate) vein that joins the left SVC. We found 15 cases (0.05%) in the CHP database and 5 additional cases in the Heart Museum. The most commonly associated anomalies were ventricular

septal defects, atrial septal defects, and atrioventricular septal defects. Rarely, the coronary sinus may also be unroofed in association with this entity. It is said that arrhythmias, including sinus node dysfunction, atrioventricular block, supraventricular tachycardia, and bundle-branch block, are more common under the circumstance of an absent right SVC. During cardiopulmonary bypass, the isolated left SVC must be cannulated directly for the management of venous return if the atrium must be opened.

septal defects, atrial septal defects, and atrioventricular septal defects. Rarely, the coronary sinus may also be unroofed in association with this entity. It is said that arrhythmias, including sinus node dysfunction, atrioventricular block, supraventricular tachycardia, and bundle-branch block, are more common under the circumstance of an absent right SVC. During cardiopulmonary bypass, the isolated left SVC must be cannulated directly for the management of venous return if the atrium must be opened.

Left Superior Caval Vein Draining Directly into the Left Atrium

A left SVC may drain directly into the left atrium. Drainage of the vena cava to the left atrium (either the left or the right SVC) was found in <0.2% of the patients in the CHP Cardiology Patient Database. Forty percent of these were patients with atrial isomerism, and 15% were also associated with an atrioventricular septal defect. When the left SVC connects directly to the left atrium, it is usually in association with abnormalities of lateralization with either right or left atrial isomerism. It is slightly more common for the SVC to drain directly into the left atrium in cases of right isomerism. In addition, the left SVC may drain directly into the left atrium without other serious cardiac malformations, causing right-to-left shunting. When this becomes hemodynamically significant, correction of the shunt may require interatrial baffling of the orifice of the left SVC to the systemic atrium or translocation of the left SVC to the right atrium or right SVC. It should be recalled that, in left isomerism, a solitary left SVC may drain directly to the systemic or right-sided atrium or through the coronary sinus.

Left superior caval drainage into the left-sided atrium must be surgically addressed when the systemic and pulmonary venous circulations are to be separated. This is most commonly encountered during the palliation or repair of various forms of the functionally univentricular heart. Under those circumstances, the left SVC may be directly connected to the left pulmonary artery (left bidirectional Glenn anastomosis) as part of a staged or total cavopulmonary connection. Interatrial tunneling of the venous return from the atrial orifice of the left SVC to the right (systemic) atrium may compromise or complicate the intracardiac repair of many defects, especially atrioventricular septal defects. Removal of the left SVC from the left atrium and direct attachment to the right-sided atrium or right SVC may be more efficacious. Cryopreserved homograft tissue may also be used as a patch or conduit to help achieve this extracardiac correction. Another option, in the presence of normal pulmonary hemodynamics, is to attach the left SVC directly to the left pulmonary artery, even when a biventricular repair is contemplated. This will correct the right-to-left shunt and still provide decompression of the left superior caval system.

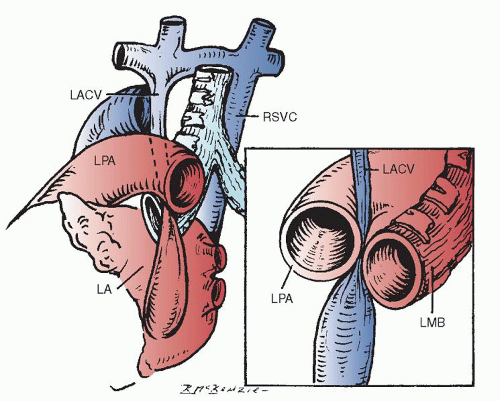

Presence of a Levoatrial Cardinal Vein

The levoatrial cardinal vein is occasionally confused with the persistence of the left SVC. However, it differs from a left SVC in several ways. The levoatrial cardinal vein is thought to result from the persistence of anatomic channels that connect the capillary plexus of the embryonic foregut to the cardinal veins. It is usually found with a normally present left innominate vein. It ascends from the left atrium or a confluence of pulmonary veins dorsal to the left pulmonary artery, passing between the left pulmonary artery and the left bronchus (Fig. 76.3). When this vein receives pulmonary venous return, the passage of the levoatrial cardinal vein between these two large and potentially fixed structures causes obstruction to the anomalously draining pulmonary venous return.

The levoatrial cardinal vein is most usually recognized in association with left atrioventricular valve stenosis or atresia and with a restrictive or absent interatrial opening. It may provide the only exit for pulmonary venous blood that arrives through normally connected pulmonary veins into the left-sided atrium in patients with left ventricular inflow obstruction. It provides an exit into the systemic venous circulation. An analysis of the CHP Cardiology Patient Database found that 0.04% of the patients had a levoatrial cardinal vein. Fifty percent of the patients had either right or left isomerism, and a small proportion of the patients had other associated anomalies, including double-outlet right ventricle, tetralogy of Fallot, ventricular septal defect, and atrioventricular septal defect.