Annuloaortic Ectasia

Tirone E. David

The term “annuloaortic ectasia” was first used by Denton Cooley in 1961 to describe aortic root aneurysm due to Erdheim’s cystic medial necrosis in a patient without the stigmata of Marfan syndrome. Although annuloaortic ectasia is often associated with aortic root aneurysm, it may also occur in patients without aneurysm but with aortic insufficiency due to bicuspid or tricuspid aortic valve disease and in those with subaortic ventricular septal defect. Conversely, not all patients with aortic root aneurysm have annuloaortic ectasia. Annuloaortic ectasia is now used to describe a dilated aortic annulus, which is often found in patients with connective disorders of the aortic root. This chapter is dedicated to surgery for aortic root aneurysm with or without annuloaortic ectasia.

The aortic root has four distinct anatomic components: aortic annulus, aortic cusps, aortic sinuses, and sinotubular junction. In addition, the triangles beneath the commissures of the aortic valve are also affected in annuloaortic ectasia, although anatomically they are part of the left ventricular outflow tract. The aortic annulus is the structure that attaches the aortic root to the left ventricle. The aortic annulus is attached to the ventricular myocardium (interventricular septum) in approximately 45% of its circumference and to fibrous structures (anterior leaflet of the mitral valve and membranous septum) in the remaining 55%. Dilation of the aortic annulus alters this relationship and occurs along the fibrous insertion of the aortic annulus. The subcommissural triangles, particularly those beneath the noncoronary cusp, tend to become more obtuse as the annulus dilates. Annuloaortic ectasia usually occurs in patients with aortic root aneurysm due to inherited connective tissue disorders such as in Marfan syndrome and others but it is also often associated with incompetent bicuspid aortic valves.

Cardiac surgery in patients with aortic root aneurysm may be necessary because of aortic insufficiency, dilation of the aortic sinuses, acute type A aortic dissection, or a combination of these problems. The first effective surgical treatment of aortic root aneurysm was described by Bentall and DeBono in 1968. It consisted in replacing the aortic valve and ascending aorta with a Dacron conduit containing a mechanical valve, and the coronary arteries were reimplanted into the graft in a side-to-side manner and the aneurysm wall wrapped around the graft to control hemorrhage. False aneurysm of this graft-to-coronary artery anastomosis was common. Reimplantation of the coronary arteries using the button technique largely resolved the problem. Composite replacement of the aortic valve and ascending aorta with a valved conduit (mechanical, biological, or bioprosthetic) became the standard treatment for patients with aortic root aneurysms for several decades. In 1992, David and Feindel and 1 year later Sarsam and Yacoub pointed out that patients with aortic root aneurysm often had normal aortic cusps and a conservative procedure, whereby the aneurysmal aortic sinuses could be excised and the aortic root reconstructed with a tubular Dacron graft was feasible. We coined the term aortic valve sparing to describe these operations to distinguish them from aortic valve repair, which largely addresses problems with the aortic cusps. There are basically two types of aortic valve–sparing operations to treat patients with aortic root aneurysms: remodeling of the aortic root and reimplantation of the aortic valve. Several modifications of these two types of aortic valve sparing have been described and although the early outcomes appear satisfactory, there are long-term data only on the two original procedures, which will be described in detail in this chapter.

AORTIC VALVE–SPARING OPERATIONS FOR AORTIC ROOT ANEURYSM

Aneurysms often alter the anatomic relationships of the various components of the aortic root (subcommissural triangles, aortic annulus, aortic cusps, aortic sinuses, and sinotubular junction) and aortic valve–sparing operations were developed to correct these abnormalities, which can be quite challenging if all components are abnormal. A sound knowledge of functional anatomy of the aortic valve and how the various components of the aortic root interplay is indispensable to perform these operations. The feasibility of an aortic valve–sparing operation is largely dependent on the quality of the aortic cusps. If the cusps are grossly abnormal, replacement of the entire aortic root is necessary.

Remodeling of the Aortic Root

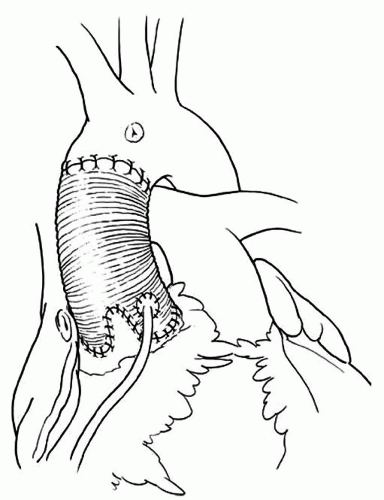

This procedure should be reserved for older patients with normal aortic annulus (e.g., ≤25 mm for women and 27 mm for men). Most of these patients have primarily ascending aorta aneurysm and the aortic sinuses become secondarily involved by a degenerative process. Remodeling of the aortic root is performed by excising the aneurysmal aortic sinuses and leaving approximately 5 mm of aortic wall attached to the annulus as illustrated in Figure 57.1. The three commissures are pulled upward and approximated until

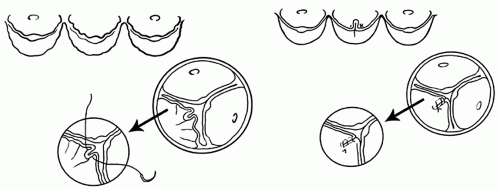

the cusps touch each other centrally, and the diameter of the imaginary circle that includes all three commissures is probably the ideal diameter of tubular Dacron graft if the cusps are not elongated. Three neoaortic sinuses (two for bicuspid aortic valves) are tailored in one of the ends of the graft. The height of the sinuses should be approximately equal to the diameter of the graft. The width of each neoaortic sinus should be proportional to the intercommissural distance. That is, larger cusps should have proportionally larger neoaortic sinuses. Next, the three commissures are sutured on the outside of the graft, immediately above the neoaortic sinuses as illustrated in Figure 57.2. The neoaortic sinuses are sutured to the remnants of arterial wall and aortic annulus with continuous 4-0 polypropylene sutures. This suture line must be carefully done with bites close together to avoid bleeding, a common complication in this operation. We do not use Teflon felt on this suture line. If the arterial wall is paper-thin, we use 5-0 polypropylene sutures in a fine needle, otherwise a 4-0 polypropylene suture in a fine needle. The coronary arteries are reimplanted in their respective neoaortic sinus. Following that, the cusps are inspected for the level of coaptation. The three cusps should coapt at the same level and several millimeters above the level of the aortic annulus. If one or more cusps appear to be coapting at a lower level than the other two, its free margin should be shortened by plication on the central portion along the nodule of Arantius as illustrated in Figure 57.3. If large stress fenestration is present, we routinely reinforce the free margin of the cusp with a double layer of a fine Gore-Tex suture (W.L. Gore & Associates, Langstaff, AZ) as illustrated in Figure 57.4. Clamping the distal end of the graft and injecting cardioplegia into the reconstructed aortic root is a reliable method to test for valve competence. Finally,

the graft is sutured to the distal ascending aorta or transverse arch graft if it also was replaced as illustrated in Figure 57.5. Valve competence is assessed by intraoperative echocardiography. In addition to a competent valve (no more than trace aortic insufficiency should be accepted), the coaptation level and coaptation length should be measured. Ideally, the coaptation height should be at least 9 mm from the nadir of the aortic annulus and the coaptation length at least 4 mm.

the cusps touch each other centrally, and the diameter of the imaginary circle that includes all three commissures is probably the ideal diameter of tubular Dacron graft if the cusps are not elongated. Three neoaortic sinuses (two for bicuspid aortic valves) are tailored in one of the ends of the graft. The height of the sinuses should be approximately equal to the diameter of the graft. The width of each neoaortic sinus should be proportional to the intercommissural distance. That is, larger cusps should have proportionally larger neoaortic sinuses. Next, the three commissures are sutured on the outside of the graft, immediately above the neoaortic sinuses as illustrated in Figure 57.2. The neoaortic sinuses are sutured to the remnants of arterial wall and aortic annulus with continuous 4-0 polypropylene sutures. This suture line must be carefully done with bites close together to avoid bleeding, a common complication in this operation. We do not use Teflon felt on this suture line. If the arterial wall is paper-thin, we use 5-0 polypropylene sutures in a fine needle, otherwise a 4-0 polypropylene suture in a fine needle. The coronary arteries are reimplanted in their respective neoaortic sinus. Following that, the cusps are inspected for the level of coaptation. The three cusps should coapt at the same level and several millimeters above the level of the aortic annulus. If one or more cusps appear to be coapting at a lower level than the other two, its free margin should be shortened by plication on the central portion along the nodule of Arantius as illustrated in Figure 57.3. If large stress fenestration is present, we routinely reinforce the free margin of the cusp with a double layer of a fine Gore-Tex suture (W.L. Gore & Associates, Langstaff, AZ) as illustrated in Figure 57.4. Clamping the distal end of the graft and injecting cardioplegia into the reconstructed aortic root is a reliable method to test for valve competence. Finally,

the graft is sutured to the distal ascending aorta or transverse arch graft if it also was replaced as illustrated in Figure 57.5. Valve competence is assessed by intraoperative echocardiography. In addition to a competent valve (no more than trace aortic insufficiency should be accepted), the coaptation level and coaptation length should be measured. Ideally, the coaptation height should be at least 9 mm from the nadir of the aortic annulus and the coaptation length at least 4 mm.

Fig. 57.3. Remodeling of the aortic root. The coronary arteries are reimplanted and the distal anastomosis is performed. |

Fig. 57.4. Repair of cusp prolapse. The free margin of the prolapsing cusps is plicated along the nodule of Arantius with fine polypropylene sutures. |

Reimplantation of the Aortic Valve

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree