Acute Rheumatic Fever: Introduction

Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) is a multisystem autoimmune disease resulting from infection with group A streptococcus. Episodes of ARF tend to recur in the same individual unless preventive measures are instituted, and each recurrence increases the chance of long-term damage to the heart valves—that is, rheumatic heart disease (RHD). Now uncommon in the developed world, ARF and RHD remain a major public health problem in developing countries and in some poor, mainly indigenous populations in wealthy countries.

Epidemiology

The incidence of ARF began to decline in developed countries toward the end of the 19th century, and by the second half of the 20th century, ARF had become rare in most affluent populations. This decline is attributed to more hygienic and less crowded living conditions, better nutrition, improved access to medical care, and, to a lesser extent, the advent of antibiotics in the 1950s. However, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 500,000 individuals acquire ARF each year, of whom 97% are in developing countries, where the incidence of ARF exceeds 50 per 100,000 children per year. Epidemiologic data from many developing countries are poor, and these are very likely to be underestimates. Much higher rates of 80 to 500 per 100,000 have been documented in careful studies in the indigenous populations of Australia and New Zealand.1 By contrast, the incidence of ARF in industrialized countries is less than 10 per 100,000 children.1,2 There have been several outbreaks of ARF in middle-class populations in the intermountain region of the United States since the mid-1980s, associated with mucoid strains of group A streptococcus, particularly of M type 18.3

The peak incidence of ARF occurs in those aged 5 to 15 years, with a decline thereafter such that cases are rare in adults older than age 35 years.1 First attacks are rare in the very young; only 5% of first episodes arise in children younger than age 5 years, and the disease is almost unheard of in those younger than age 2 years.4 Recurrent attacks are most frequent in adolescence and young adulthood and are diagnosed infrequently after age 45 years.

ARF is equally common in males and females, but RHD is more common in females. Whether this trend is a result of innate susceptibility, increased exposure to group A streptococcus because of greater involvement of women in child rearing, or reduced access to preventive medical care for females is unclear.1 No association with ethnic origin has been found. There is some evidence that between 3% and 6% of any population is susceptible to ARF.5

Pathogenesis

Epidemiologic and immunologic evidence clearly implicates group A–β-hemolytic streptococcus in the initiation of the disease in a susceptible host. Most patients with ARF have elevated titers of antistreptococcal antibodies. Outbreaks of ARF usually follow epidemics of streptococcal pharyngitis. Adequate treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis reduces the incidence of subsequent ARF, and appropriate antimicrobial prophylaxis prevents recurrences after initial attacks.6,7

It has generally been considered that certain strains of group A streptococcus are more prone to result in ARF, and this “rheumatogenicity” was thought to be a feature of strains belonging to certain M serotypes. More recent studies suggest that rheumatogenicity may not be serotype specific. The long-held opinion that only streptococcal pharyngitis, and not streptococcal skin infections such as impetigo, may be followed by ARF has also been challenged.8 Studies in populations where ARF is common find no definite association between group A streptococcal sequence type and site of infection or ability to cause disease.9,10 Thus the distinction between rheumatogenic and nonrheumatogenic strains, and between those trophic for the skin or throat, is considered by some to become blurred in areas where ARF is common, and multiple different group A streptococcal strains circulate within small populations.1

Host factors have been considered to be important ever since familial clustering was reported last century. Associations between disease and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II alleles have been identified, but the alleles associated with susceptibility or protection differ depending on the population investigated.11 High concentrations of circulating mannose-binding lectin and polymorphisms of transforming growth factor-β1 and immunoglobulin genes also are associated with ARF.12-14

Certain B-cell alloantigens are expressed to a greater level in patients with ARF or RHD than controls, with family members having intermediate expression, suggesting that these antigens are markers of inherited susceptibility. The best characterized is D8/17, which is associated with ARF and RHD in several populations worldwide.15 Further investigation is needed before B-cell alloantigen markers can be used to identify individuals with, or at risk for, ARF or RHD. There is, as yet, no specific investigation that reliably identifies individuals who are at risk of ARF or who will develop chronic rheumatic valvular heart disease.

The molecular mimicry theory holds that antibodies or cellular immune responses directed against group A streptococci cross-react with epitopes on host tissue.16 Streptococcal M protein and a carbohydrate streptococcal antigen (N-acetylglucosamine in group A carbohydrate) share epitopes with cardiac myosin and valve tissue. There is no myosin in cardiac valves, the main site of human cardiac damage, but it is known that laminin in valvular basement membrane is recognized by T cells against myosin and the M protein. Antibodies to valve tissue cross-react with N-acetylglucosamine in group A carbohydrate.1 In an animal model, antibodies that caused chorea bound to both the carbohydrate antigen and mammalian lysoganglioside.

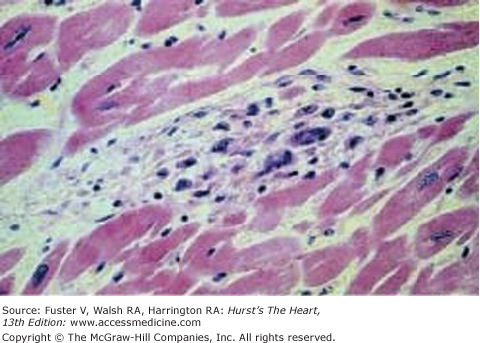

The exact mechanism of the initial insult is unclear. Subsequent damage appears to be caused by T-cell and macrophage infiltration, which persists for years after the initial event.11 The pathologic lesion of ARF is the Aschoff body, a granulomatous lesion containing T and B cells, macrophages, large mononuclear cells, multinucleated giant cells, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the myocardium (Fig. 75–1).17

Figure 75–1.

Aschoff body. A myocardial Aschoff body that is characterized by a nodular aggregate of large mononuclear and multinuclear cells. Reproduced with permission from Binotto et al.17

Clinical Presentation

The protean manifestations of this condition were well described in the middle of the last century. The Jones criteria, established in 1944 and modified and updated subsequently (Table 75–1), are the current gold standard for diagnosis.18,19 Revisions of the Jones criteria have increased specificity but decreased sensitivity. Overreliance on the Jones criteria in areas where ARF is common may result in missed diagnoses and failure to provide secondary prophylaxis to deserving patients.

| Diagnostic Categories | Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Primary episode of rheumatic fever. | Two majora or one major and two minorb manifestations plus evidence of a preceding group A streptococcal infection.c |

| 2. Recurrent attack of rheumatic fever in a patient without established rheumatic heart disease. | As for a primary episode of rheumatic fever. |

| 3. Recurrent attack of rheumatic fever in a patient with established rheumatic heart disease. | Two minor manifestations plus evidence of a preceding group A streptococcal infection. |

| 4. Rheumatic chorea. | Other major manifestations or evidence of group A streptococcal infection are not required because these are delayed manifestations of streptococcal infection. |

| 5. Insidious onset rheumatic carditis. | |

| 6. Chronic valve lesions of rheumatic heart disease, ie, patients presenting for the first time with pure mitral stenosis or mixed mitral valve disease with or without aortic valve disease. | Do not require any other criteria to be diagnosed as having rheumatic heart disease. |

The disease usually has an acute febrile onset and variable combinations of arthritis and arthralgia, carditis, chorea, and skin manifestations.