Acquired Cardiac Disease

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States. Patients with acquired heart disease can present with classic clinical syndromes, such as angina and myocardial infarction or with vague symptoms such as fatigue or shortness of breath. However, many patients with heart disease present with atypical clinical signs and symptoms or are entirely free of any sign of disease. Radiologists play a key role in making the initial diagnosis of heart disease in many cardiac patients. Imaging is also one of the most important tools used to assess the effectiveness of treatment of cardiovascular disease. In this chapter we cover the basic imaging features of adult acquired heart disease, with an emphasis on chest radiography. Table 20.1 provides an outline of topics covered.

Cardiac Valve Disease

Mitral Valve Disease

According to the American Heart Association 2000 statistical update (1), there were 40,000 hospital discharges secondary to mitral valve disease in the year 2000. Approximately 2,500 U.S. citizens died, and 6,100 other deaths involved mitral disease as a contributing factor. Pure mitral stenosis comprises 25% of all cases of mitral disease, pure insufficiency 37%, and combined mitral stenosis and insufficiency 39% (2). Postinflammatory disease (chronic fibrosis) commonly causes mitral stenosis, whereas floppy valve and inflammatory disease are the most common causes of mitral insufficiency.

Combined mitral stenosis and insufficiency is more common than isolated stenosis or isolated insufficiency.

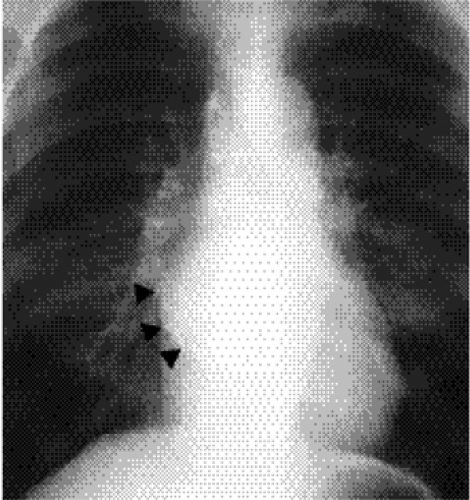

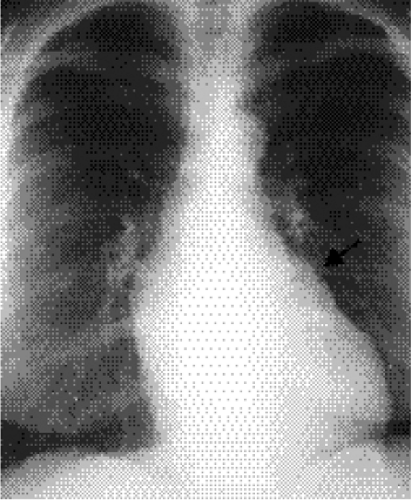

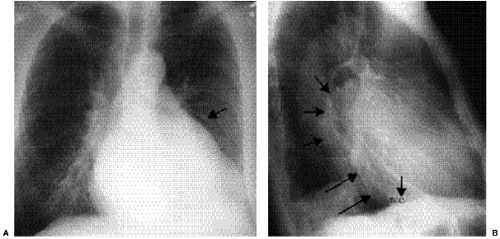

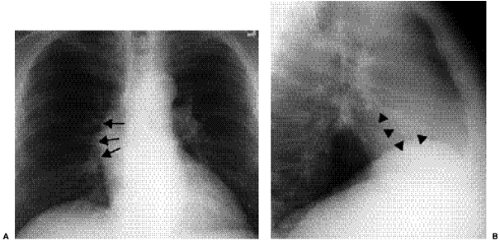

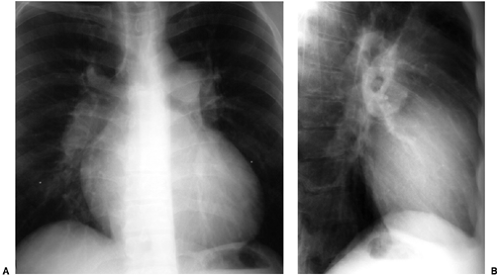

The radiographic diagnosis of mitral valve disease centers on detection of a dilated left atrial chamber (Table 20.2). It should be mentioned, however, that the left atrial volume must increase more than 200% to be detected on radiography (3). The “double density” sign occurs in the frontal projection when the left atrial opacity projects through the right atrial outline (Fig. 20.1). The left atrium can be seen normally through the right atrium but should be considered enlarged when the distance between the right lateral margin of the left atrium and the bottom of the mid-point of the left main bronchus measures more than 7 cm (4). Focal enlargement of the left atrial appendage in the frontal view is an additional important sign of mitral disease (Fig. 20.2). The enlarged atrial appendage projects as a local bump along the left heart outline, below the level of the left main bronchus. This

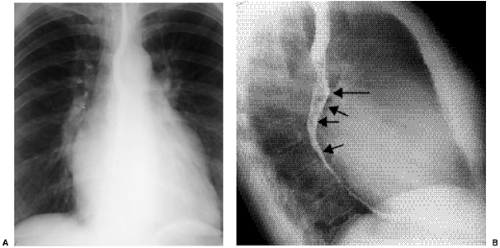

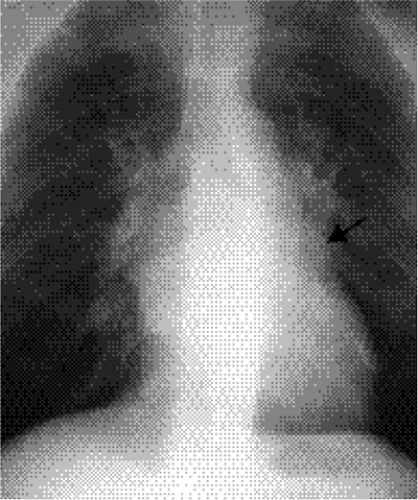

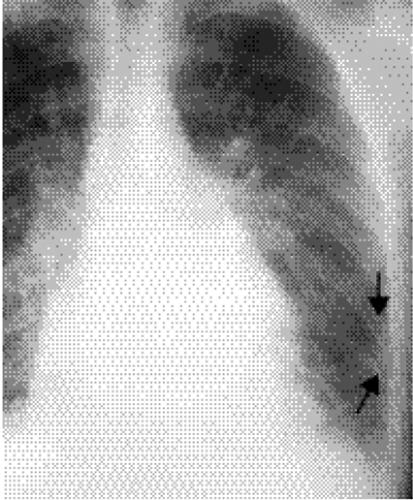

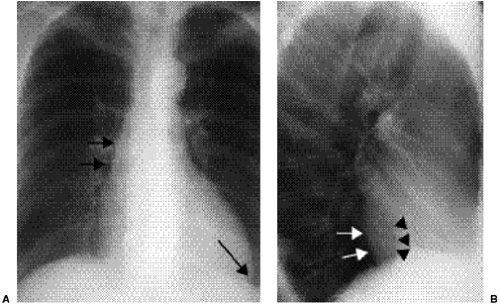

bump is often called the “fourth mogul,” because the enlarged appendage opacity is in addition to the normally found opacities of the aortic arch, left pulmonary artery, and lateral margin of the left ventricle. However, enlargement of the appendage is sometimes absent in left atrial dilatation. This lack of enlargement of the left atrial appendage sometimes indicates thrombosis of the appendage (5). The appendage is most commonly enlarged when the valve disease is rheumatic in origin and is less likely enlarged when the cause is nonrheumatic (6). In some patients the left main bronchus is displaced upward and backward, although this is not a very reliable sign (7). Posterior displacement of the upper posterior cardiac margin and carina or left lower lobe bronchus can also be seen in the lateral view (Fig. 20.3). Focal displacement of a barium-filled esophagus was used in the past, before introduction of echocardiography, to show left atrial enlargement (Fig. 20.4).

bump is often called the “fourth mogul,” because the enlarged appendage opacity is in addition to the normally found opacities of the aortic arch, left pulmonary artery, and lateral margin of the left ventricle. However, enlargement of the appendage is sometimes absent in left atrial dilatation. This lack of enlargement of the left atrial appendage sometimes indicates thrombosis of the appendage (5). The appendage is most commonly enlarged when the valve disease is rheumatic in origin and is less likely enlarged when the cause is nonrheumatic (6). In some patients the left main bronchus is displaced upward and backward, although this is not a very reliable sign (7). Posterior displacement of the upper posterior cardiac margin and carina or left lower lobe bronchus can also be seen in the lateral view (Fig. 20.3). Focal displacement of a barium-filled esophagus was used in the past, before introduction of echocardiography, to show left atrial enlargement (Fig. 20.4).

Left atrial volume must be twice that of normal to be detectable radiographically.

Focal left atrial appendage enlargement (the “fourth mogul” on a posteroanterior chest radiograph) should raise suspicion of mitral valve disease.

Table 20.1: Outline of Topics: Imaging of Adult Acquired Heart Disease | |

|---|---|

|

Table 20.2: Chest Radiograph Signs of Left Atrial Enlargement | |

|---|---|

|

Figure 20.3 Lateral chest radiograph on the same patient with mitral stenosis shown in Fig. 20.1. The upper portion of the posterior margin of the heart, formed by the posterior wall of the enlarged left atrium, bulges posteriorly (arrowheads). |

Mitral Valve Stenosis

The underlying functional abnormality in mitral valve stenosis relates to obstruction at the valve with a pressure gradient between the atrium and left ventricle. As a result of the obstruction left atrial pressure elevates, with corresponding elevation of the pulmonary venous, capillary, and arterial pressures. As capillary pressure rises, blood flow can redistribute from the bases into the upper portions of the lungs (“cephalization” or “redistribution”) (Fig. 20.5). Increased blood flow in the upper portions of the lungs produces increased diameters of arteries and veins in the upper lungs, with corresponding decreased

sized vessels in the lung bases. This sign can be seen on occasion in upright patients, where blood flow ordinarily dominates in the dependent portions of the lungs. Cephalization of pulmonary blood flow can only be diagnosed in upright patients who have clear lungs at full inspiration. When pulmonary capillary pressure rises further, hydrostatic pressure in the capillary bed overcomes colloid osmotic pressure. Thus, fluid extravasates into the interstitium of the lungs, creating Kerley lines, linear opacities representing fluid in interlobular septa (Fig. 20.6). The left ventricle maintains a normal size in mitral stenosis.

sized vessels in the lung bases. This sign can be seen on occasion in upright patients, where blood flow ordinarily dominates in the dependent portions of the lungs. Cephalization of pulmonary blood flow can only be diagnosed in upright patients who have clear lungs at full inspiration. When pulmonary capillary pressure rises further, hydrostatic pressure in the capillary bed overcomes colloid osmotic pressure. Thus, fluid extravasates into the interstitium of the lungs, creating Kerley lines, linear opacities representing fluid in interlobular septa (Fig. 20.6). The left ventricle maintains a normal size in mitral stenosis.

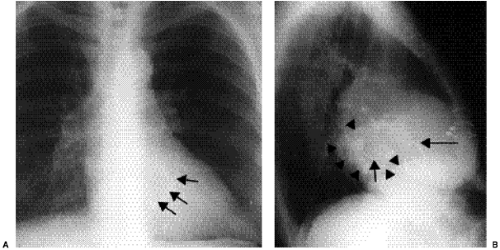

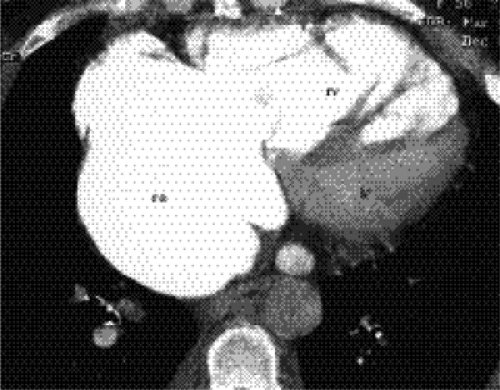

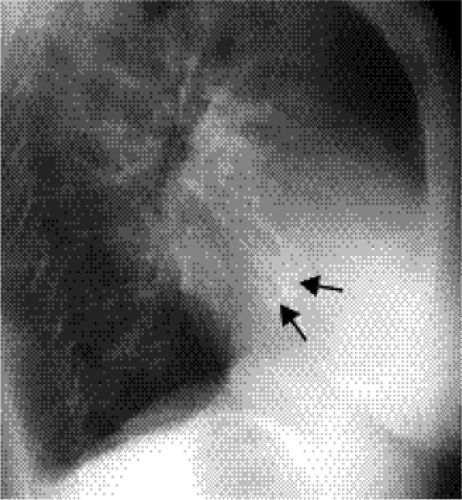

Right-sided chambers can enlarge secondary to chronic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Identification of mitral valve leaflet calcification can be helpful in diagnosing mitral valve stenosis, although large amounts of valve leaflet calcification are necessary for the calcific opacity to become visible on the lateral chest radiograph (Fig. 20.7). Most patients do not have enough calcification to be detected on radiographs. Valve calcification should be distinguished from the commonly seen “C-shaped” calcification of the mitral annulus

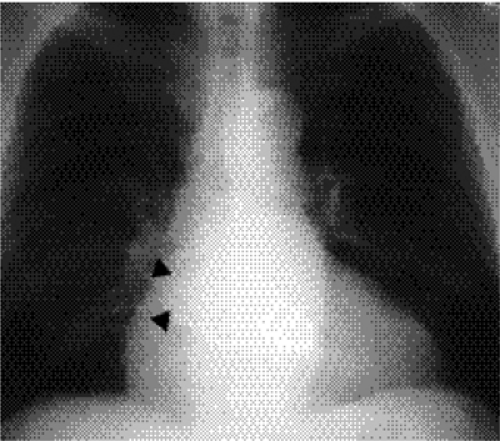

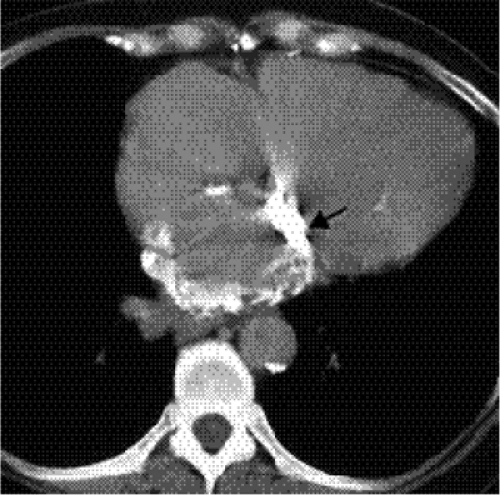

(Figs. 20.8A and B). Calcification of the annulus is common in the elderly, possibly related to systemic atherosclerosis (8). Uncommonly, calcific deposits in the wall of the left atrium are shown on chest radiographs (Fig. 20.9) or computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 20.10). Left atrial wall calcification is often associated with a history of rheumatic fever, and the calcification is therefore likely due to rheumatic carditis (9). Mural thrombi in the left atrium can also calcify.

(Figs. 20.8A and B). Calcification of the annulus is common in the elderly, possibly related to systemic atherosclerosis (8). Uncommonly, calcific deposits in the wall of the left atrium are shown on chest radiographs (Fig. 20.9) or computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 20.10). Left atrial wall calcification is often associated with a history of rheumatic fever, and the calcification is therefore likely due to rheumatic carditis (9). Mural thrombi in the left atrium can also calcify.

Figure 20.7 Lateral chest radiograph of a 73-year-old patient with mitral stenosis. There is heavy calcification in the mitral valve (arrows). |

Mitral annulus calcification may be an indication of atherosclerosis but is not an indicator of mitral valve stenosis or insufficiency.

A calcified left atrial wall should raise suspicion of rheumatic mitral valvular disease.

Mitral Valve Insufficiency

Incompetence of the mitral valve can be due to a variety of pathologic conditions. Postinflammatory disease (usually rheumatic), floppy valve, ischemic heart disease, endocarditis,

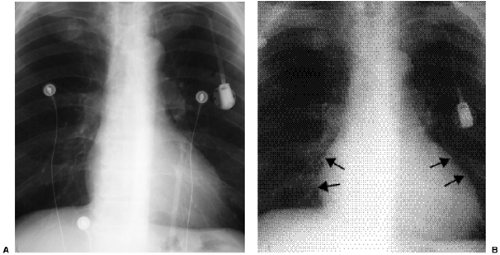

idiopathic rupture of chordae, and cardiomyopathy are etiologic possibilities. Chest radiographs show left atrial dilatation, and the degree of enlargement can be quite marked. In contrast with mitral stenosis, the left ventricle also dilates (Fig. 20.11). Left ventricular dilatation is due to the demand for increased left ventricular stroke volume in light of the regurgitant flow fraction. Redistribution of blood flow is uncommon in pure chronic mitral regurgitation, as is pulmonary edema, because left atria can be compliant with normal

left atrial pressures (10). If heart failure occurs, redistribution and pulmonary edema can be seen on chest radiographs. Pulmonary edema is more apt to occur in acute mitral regurgitation due to ruptured chordae and acute ischemia of the papillary muscles, sometimes with atypical distribution of pulmonary edema predominating in the right upper lobe (Fig. 20.12) (11).

idiopathic rupture of chordae, and cardiomyopathy are etiologic possibilities. Chest radiographs show left atrial dilatation, and the degree of enlargement can be quite marked. In contrast with mitral stenosis, the left ventricle also dilates (Fig. 20.11). Left ventricular dilatation is due to the demand for increased left ventricular stroke volume in light of the regurgitant flow fraction. Redistribution of blood flow is uncommon in pure chronic mitral regurgitation, as is pulmonary edema, because left atria can be compliant with normal

left atrial pressures (10). If heart failure occurs, redistribution and pulmonary edema can be seen on chest radiographs. Pulmonary edema is more apt to occur in acute mitral regurgitation due to ruptured chordae and acute ischemia of the papillary muscles, sometimes with atypical distribution of pulmonary edema predominating in the right upper lobe (Fig. 20.12) (11).

In mitral insufficiency, the left atrium and left ventricle are enlarged because of increased blood volume from the “regurgitated” blood. In contrast, only the left atrium is enlarged with mitral stenosis.

Aortic Valve Disease

The American Heart Association 2000 statistical update states that 11,600 patients died of aortic valve disease, with 24,000 having aortic valve disease mentioned as a contributing factor. There were 40,000 hospital discharges with this diagnosis. Most cases of aortic valve disease occur in conjunction with a congenital bicuspid valve or secondary to degenerative and postinflammatory diseases (12,13,14). As our population ages, the proportion of patients with a degenerative etiology is increasing (15,16).

Aortic Stenosis

The pathophysiology of aortic stenosis is based on outflow obstruction, left ventricular pressure overload, and increased myocardial wall thickness. Heart size remains normal until heart failure occurs, an ominous clinical sign. With concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricle, sometimes the left cardiac margin on the frontal view has a somewhat rounded configuration. However, the primary signs of aortic valve stenosis include poststenotic dilatation of the ascending aorta and aortic valve calcification (Fig. 20.13). Poststenotic dilation of the ascending aorta evolves with the chronic stress of a jet of blood flow that impacts the aortic wall. Calcification of the valve is common and increases with age. In fact, calcification in the aortic valve without any functional obstruction occurs in one in four or five patients over 65 years of age. The valve calcification is best seen on the lateral view, because the valve usually projects over the spine in the frontal projection. When calcification is observed on chest radiographs of younger individuals or is associated with signs and symptoms of heart failure, aortic stenosis should be suggested. Incidental observation of aortic valve calcification on chest CT occurs frequently and is usually clinically insignificant. However, abundant aortic valve calcification found on CT in patients less than 55 years of age should be considered possible aortic stenosis (17).

Aortic stenosis with left ventricular failure is a poor prognostic sign.

Aortic valve calcification is common in adults over 65 years of age. When seen in younger individuals, it should raise suspicion of aortic valvular stenosis.

Aortic Valve Insufficiency

Aortic valve insufficiency, or regurgitation, creates a volume load on the left ventricle. The causes of aortic insufficiency are listed in Table 20.3. Left ventricular stroke volume must

increase to compensate for regurgitation to maintain normal forward cardiac output. By way of illustration, to maintain forward cardiac output of 5 L/min in a patient with 5 L/min of regurgitant flow, there would be a need for a left ventricular output of 10 L/min.

increase to compensate for regurgitation to maintain normal forward cardiac output. By way of illustration, to maintain forward cardiac output of 5 L/min in a patient with 5 L/min of regurgitant flow, there would be a need for a left ventricular output of 10 L/min.

An enlarged left ventricle and ascending aorta should raise suspicion for aortic valvular insufficiency.

The left ventricle dilates in cases of aortic valve insufficiency, and the thoracic aorta can dilate. The degree of aortic dilatation varies on chest radiography, but identification of left ventricular dilatation is necessary for radiologists to make a diagnosis of aortic regurgitation. The cardiac outline enlarges, and the apex in the frontal view is often displaced laterally and inferiorly toward the costophrenic angle (Fig. 20.14). In the frontal view the dilated ascending aorta can displace the mid-mediastinal outline to the right and the aortic arch can enlarge. In the lateral view, the left ventricle lies inferior and posterior relative to the other cardiac chambers. When dilated, the left ventricle projects more than 18 mm posterior to the inferior vena cava, often intersecting the diaphragm behind the inferior vena cava (18).

Aortic and mitral valvular disease commonly coexist. The valve leaflets are in direct physical continuity, permitting an inflammatory process such as rheumatic disease to involve both valves. This is known as Lutembacher syndrome.

Pulmonic and Tricuspid Valve Disease

The incidence of acquired disease confined to the pulmonic and tricuspid valves is low compared with mitral and aortic valve disease (Table 20.4). The American Heart Association 2000 statistical update reveals only 11 patient deaths due to primary disease of the

right-sided cardiac valves (1). Most commonly, primary disease of the right-sided valves is due to rheumatic disease, almost always associated with disease also involving the left-sided cardiac valves. Carcinoid disease is uncommon and rarely recognized on radiographs (Fig. 20.15). Secondary disease of these valves due to pulmonary hypertension is more common (19).

right-sided cardiac valves (1). Most commonly, primary disease of the right-sided valves is due to rheumatic disease, almost always associated with disease also involving the left-sided cardiac valves. Carcinoid disease is uncommon and rarely recognized on radiographs (Fig. 20.15). Secondary disease of these valves due to pulmonary hypertension is more common (19).

Table 20.3: Causes of Aortic Valve Insufficiency | |

|---|---|

|

Pulmonary Hypertension

Pulmonary hypertension results in right atrial and ventricular pressure and/or volume overload, with enlargement of these chambers (Fig. 20.16). Pulmonic and tricuspid valve insufficiency are common sequelae (Fig. 20.17). Frontal chest radiographs show rounded enlargement of the left cardiac margin with upward displacement of the cardiac apex, representing right ventricular enlargement. Right atrial dilatation causes increased circumference and lateral displacement of the right cardiac margin. The pulmonary arteries are enlarged. The dilated right ventricle can be detected in the lateral view as fullness behind the sternum, although this is not a reliable radiographic sign (20).

Table 20.4: Causes of Acquired Pulmonic and Tricuspid Valve Disease | |

|---|---|

|

Myocardial Disease

Cardiomyopathy

The American Heart Association reports that 29,000 patients died because of cardiomyopathy in 2000 (1). The diagnosis of cardiomyopathy was mentioned in the deaths of 53,000 individuals. The cardiomyopathies can be categorized by etiologic or functional classification schemes (Table 20.5).

Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy is a disease characterized by dilatation of both ventricles or of the left ventricle alone. The true incidence of this disease is difficult to determine, because many cases are unrecognized. The annual incidence is reported to be 36 cases per 100,000 in the United States annually, with 10,000 deaths (21). Almost half of the cases are “idiopathic,” although some investigators have implicated a viral-immune etiology in these cases. Secondary dilated cardiomyopathy can be caused by a variety of etiologies (22) (Table 20.6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree