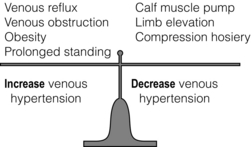

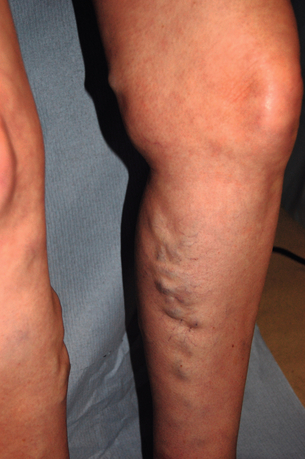

17 Varicose veins are common, often leading to a significant impact on patient quality of life, and the management of venous disease is a major cause of United Kingdom National Health Service (NHS) expense.1–4 In view of the wide range of clinical presentations, a variety of clinical teams may be involved in the management of patients with venous disease and associated complications, including vascular surgeons, dermatologists, plastic surgeons and other specialists. Clinicians and researchers have generally underestimated the clinical importance of this condition, but recent advances in treatment have stimulated a spate of research in this field. Optimal patient management involves a detailed assessment and evaluation of the patient expectations from treatment in addition to targeted multimodal therapy to address underlying anatomical abnormalities and reduce venous hypertension. The underlying cause of venous disease is chronic venous hypertension. This is usually due to venous reflux secondary to vein valve incompetence, but may also be due to occlusive deep venous disease (usually due to thrombosis) and calf muscle pump failure (usually due to ankle stiffness or poor calf muscle bulk).5 The clinical consequence of venous reflux depends not only on the severity of reflux, but also the effectiveness of normal measures that reduce venous hypertension (Fig. 17.1), ranging from asymptomatic to ulceration. The belief that venous skin changes and ulceration are only due to deep venous disease has been disproved in recent years; anatomical studies have clearly demonstrated that patients with chronic venous ulceration often have superficial reflux only.6 Chronic venous hypertension (insufficiency) is dealt with in more detail in the next chapter on chronic leg swelling. Varicose veins are usually due to superficial venous reflux affecting the great saphenous vein (GSV) (Fig. 17.2), small saphenous vein (SSV) or non-truncal veins. Whether the valve failure is a primary phenomenon or secondary to vein wall dilatation remains unknown. Two theories have been proposed to explain the development of superficial venous reflux leading to varicose veins. The ‘descending theory’ was popularised by Trendelenburg in the 19th century and suggests that superficial venous incompetence begins at the saphenous junctions and progresses distally.7 The ‘ascending theory’ advocates the proximal progression of distal venous incompetence and is supported by the observation that superficial venous incompetence often occurs with a competent saphenous junction.8 Although both explanations have merits and proponents, the development of varicose veins is likely to be multifactorial. The incidence of venous disease in the population has been evaluated by large population studies from Edinburgh and Bonn.9–11 These observational studies have demonstrated that the majority of adults have reticular or thread veins, whereas varicose veins or more severe stages of venous disease (CEAP C2–C6, see Box 17.1) are present in 25–40% of the population. Venous disease is more common in developed rather than developing countries, although the reasons for these differences are poorly understood. Interestingly, deep reflux was more common in men, whereas superficial reflux had a higher incidence in women.9–11 Overall, the incidence of venous disease was similar in males and females, which is contrary to most clinical studies, where a female preponderance of 3–4:1 is commonly reported. This discrepancy may reflect differences between the sexes in symptoms experienced, or in the threshold to seek medical advice.The prevalence of chronic venous ulceration (CEAP C6) is 0.3–1.0% and venous skin changes (CEAP C4–C5) were present in 5–10%. For all stages of venous disease, the incidence increases with age. Patients with venous disease may seek medical help for a variety of reasons. The Edinburgh Vein Study showed an inconsistent and gender-dependent relationship between a range of lower limb ‘venous’ symptoms (heaviness/tension, feeling of swelling, aching, restless leg, cramps, itching, tingling) and the presence and severity of thread, reticular or varicose veins. Clinical experience also suggests that there is little concordance between the size and extent of varicose veins and the severity of presenting symptoms. However, venous symptoms correlate with severity of venous reflux on duplex imaging.12 The CEAP classification was devised in 1994, revised in 2004, and offers a useful and widely used tool to describe a patient using Clinical, aEtiological, Anatomical and Pathophysiological criteria (Box 17.1).13 The clinical component of the CEAP classification is often used in isolation. Nevertheless, the widespread adoption of this system to characterise venous disease has been a significant advance. Other recognised scoring systems include the venous clinical severity score (VCSS) and venous disability score (VDS).14,15 These refer to small, superficial veins that may be highly visible and cause cosmetic concern (Fig. 17.3). Thread veins (also known as spider veins, telangiectasia, venous flare) are < 1 mm, whereas veins of 1–3 mm are termed reticular veins. Superficial, tortuous veins > 3 mm are considered varicose veins. Patients with thread or reticular veins may find them unsightly and request treatment. Although not usually funded by state healthcare systems, these veins can be effectively treated using injection sclerotherapy, after underlying truncal reflux has been addressed. Chronic venous hypertension is associated with a number of skin changes (Fig. 17.4), including: • Venous eczema (also known as ‘venous stasis dermatitis’). Itchy, dry and scaly skin is a common early skin change due to venous hypertension. As with most venous skin changes, eczema often occurs on the medial aspect of the lower leg (the ‘medial gaiter area’). • Haemosiderinosis and pigmentation. Chronic venous hypertension may lead to extravasation of red blood cells, resulting in pigmentation due to haemosiderin deposition in the subcutaneous tissues. There is often an associated inflammatory response, which may mimic cellulitis (see ‘Lipodermatosclerosis’ below). Once the inflammation has settled, pigmentation is generally considered permanent, despite subsequent treatment. • Lipodermatosclerosis. Chronic venous hypertension and inflammation may result in fibrosis and thickening of the skin and subcutaneous fat in the lower leg, with the classic ‘inverted champagne bottle’ appearance. Acute inflammation due to venous hypertension may be referred to as ‘acute lipodermatosclerosis’. As with haemosiderinosis, chronic skin and subcutaneous changes are generally considered irreversible. The primary aim of venous treatment is usually to reduce symptoms and prevent disease progression. • Corona phlebectatica. Also referred to as ‘malleolar flare’, this refers to a leash of prominent intradermal veins, located around the medial malleolus. The skin is often fragile and patients may progress to venous ulceration. • Atrophie blanche. Literally translated as ‘white atrophy’, this refers to a pale, smooth scarring that may occur at the site of previous ulceration. Venous ulceration is considered the worst extreme in the spectrum of chronic venous disorders and affects up to 1% of the adult population (increased in patients > 65 years16). This may be defined as a full-thickness defect of the skin of > 4 weeks duration, and commonly occurs on the medial aspect of the lower leg. Other signs of chronic venous hypertension may be present, helping to differentiate chronic venous ulcers from other causes of leg ulceration. Ulcers are usually superficial and although a healthy granulating base is commonly seen, healing times are generally protracted. Microbiological swabs of the ulcer base commonly grow a variety of organisms, but antibiotic therapy is rarely required. A detailed history of the presenting symptoms should be elucidated and potential non-vascular causes should be excluded (particularly orthopaedic and arterial disorders). It is important to describe the impact of symptoms on patient quality of life as the decision to treat and the treatment modality will usually be guided by these considerations. Cosmetic appearance is a common concern and should always be a consideration when planning intervention. Other common symptoms include heaviness, aching, itching, cramping or ‘tingling’. The correlation between the size of veins and the severity of symptoms reported by the patient is often poor. Those involved in the management of patients with varicose veins should consider that this patient group accounts for a significant proportion of medicolegal claims in surgical specialities.17 Discontent after treatment is often due to recurrent/residual varicose veins or neurological symptoms. Specific features that should be elucidated in the history include: • scars and evidence of previous venous interventions; • distribution and extent of varicosities (the examiner should specifically document the presence of a saphenovarix and other particularly large or troublesome varicosities); • presence of skin changes of chronic venous disease (oedema, pigmentation, lipodermatosclerosis, ulceration); • arterial status (pulses, or ankle brachial pressure index); • other factors contributing to venous hypertension (immobility, obesity, ankle stiffness, poor calf muscle bulk); In recent years, colour duplex ultrasound scanning (DUS) has become established as the ‘gold standard’ investigation for patients with venous disease.18 Use of this non-invasive imaging modality can accurately identify the presence of reflux or occlusion in deep and superficial venous systems. Increasing availability and reducing cost of duplex machines has meant that appropriately trained vascular surgeons are able to perform scans in the outpatient clinic and during interventions to improve outcomes. Routine duplex imaging prior to venous intervention should be considered mandatory.19 • accurate characterisation of pattern of superficial reflux (including incompetent perforating veins); • identification of deep venous disease; • assessment of suitability of superficial veins for endovenous intervention (see ‘Treatment’ section); • accurate evaluation of recurrent varicose veins; • Venography using cross-sectional imaging. Venous assessment may be performed using computerised tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These investigations may be valuable in visualising iliac veins and the inferior vena cava, as well as identifying sources of pelvis vein incompetence.20 • Invasive venography. Traditional diagnostic venography (also known as phlebography) for the assessment of superficial veins has virtually no role in modern clinical practice. Venography to assess deep veins may have some value in patients being treated with thrombolysis for DVT and the small group of patients being considered for deep venous reconstruction. • Haemodynamic assessments. A variety of tools are available to assess haemodynamic venous function in the leg. Ambulatory venous pressure (AVP) monitoring is considered the ‘gold standard’, but is invasive and limited to research use. Potential clinical benefits of digital photoplethysmography and other minimally invasive assessments of venous hypertension have been reported, but these techniques are rarely used in practice.21 • elderly patients with significant comorbidity; • patients with mild symptoms, or symptoms that may not be due to venous disease; • patients unwilling to accept the risks of surgical or endovenous interventions. A number of venoactive drugs have been studied in patients with venous disease. A large number of studies have evaluated micronised purified flavonoid fraction (Daflon, Servier) and demonstrated that venous symptoms may be reduced, but this is not available in the UK or North America. Small studies have suggested potential benefits with rutins and horse chestnut seed extract, although their use is limited.22 Compression therapy has been used for the treatment of venous disease for centuries and remains the mainstay of management for patients with venous ulceration.23 For patients with healed venous ulceration (CEAP C5), the use of elastic compression stockings has been shown to reduce the risk of recurrent ulceration.24 For patients with CEAP C2–C4 disease, stockings are prescribed frequently, but the evidence for benefit is less clear. Potential benefits include: • improvement of venous symptoms; • concealment of visible varicosities; • prevention of disease progression; • aiding clinical assessment in patients where there may be uncertainty about the extent to which the symptoms are attributable to venous disease. Compression stockings may be classified by the sub-bandage pressure applied at the ankle. Using the British standard system for classification, class I stockings apply 14–17 mmHg, class II 18–24 mmHg and class III 25–35 mmHg. In practice, patients are often unable to tolerate stockings greater than class I and many patients find class III stockings virtually impossible to put on or remove. Before commencing compression therapy, arterial disease should be excluded (by clinical assessment ± ankle–brachial pressure index measurement). Great care should be taken to fit stockings correctly and to avoid rolling down of the stocking, as this may cause pressure damage to the skin or create a tourniquet effect. Patient compliance remains a major problem with compression stockings, as they may be itchy, hot (particularly in summer months), and difficult to put on and take off, despite the availability of applicator devices. Moreover, any benefit from compression stockings only lasts as long as they are worn and they need to be replaced regularly. Studies have suggested that compliance may be as low as 50% overall and probably much lower with class III stockings.25 In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the efficacy of compression stockings, the paucity of high-quality evidence was highlighted.26 Although a number of prospective studies were identified, there was significant heterogeneity in patient population, type of compression and outcome measures evaluated. The authors found that wearing compression stockings improved symptom management, although the high number of non-compliant patients, who were excluded, could be a confounding factor. Compression was also found to reduce oedema, but the suggestion that wearing compression can slow the progression or reduce recurrence after intervention was not supported by the published literature. The underlying principle of treating patients with symptomatic superficial venous reflux is to remove or obliterate the incompetent venous channel. The treatment of patients with mixed superficial and deep venous reflux presents a challenge. In general, these patients can be safely treated with superficial venous intervention and, in some cases, the refluxing deep veins may even become competent (possibly because the incompetent venous reservoir is removed).6 However, the level of expected benefit is difficult to predict, as residual deep venous reflux may be a significant cause of venous hypertension. A trial of compression stockings (which generally compress superficial veins only) is a useful test in these circumstances and tourniquet tests using haemodynamic evaluation (digital photoplethysmography) have also been proposed. The treatment of superficial veins in patients with deep venous occlusion is not advisable, as these channels may be contributing to venous drainage, even if incompetent. In view of the high number of medicolegal claims following procedures for varicose veins, the process of consent is worthy of specific mention.27 Patients should be specifically warned of common complications such as bruising and paraesthesia. They should also understand that veins may (and often do) recur and they may suffer DVT or nerve pain. In patients with visible varicosities, they should appreciate that some residual veins may be present and their legs will not be cosmetically perfect. Other complications associated with specific procedures are described below. Information leaflets should be used, specific consent forms may be useful and discussions with the patient should be clearly documented in the medical records. Perhaps most importantly, the patient’s expectations from treatment should be clarified before intervention and match those of the treating clinician. Trendelenburg described ligation of the proximal GSV in 189028 and modifications of this technique have remained the mainstay of treatment for varicose veins for over a century. With the increasing popularity of minimally invasive, endovenous modalities, the proportion of patients treated with surgical stripping has declined in recent years.29 With the development of efficient day case units, virtually all varicose vein operations can be performed as day case procedures. Although the majority of procedures are performed using general anaesthesia, regional or local techniques may also be used. Epidural/spinal anaesthesia or femoral nerve blocks can facilitate surgery, but the motor block may persist for several hours, potentially hindering same-day discharge. Surgical stripping may also be performed using dilute local anaesthesia with adrenaline, injected in high volumes around the vein to be stripped (‘tumescent’ anaesthesia – see below). However, in a generally young and fit patient group, most surgeons (and anaesthetists) favour general anaesthesia for traditional varicose vein surgery. The routine use of prophylactic antibiotics has been shown to reduce the risk of wound complications in one randomised study.30

Varicose veins

Introduction

Pathophysiology

Chronic venous hypertension

Varicose veins

Epidemiology and natural history

Clinical presentation

Thread veins and reticular veins (CEAP C1)

Oedema and skin changes (CEAP C3–C4)

Chronic venous ulceration (CEAP C5–C6)

Clinical assessment

Patient examination

Venous investigations

Duplex ultrasound scanning

Other investigations

Treatment

Conservative options, drugs and compression therapy

Pharmacotherapy

Compression stockings

Principles of surgical and endovenous intervention

Pre-procedure marking

Informed consent

Traditional surgery

Setting and anaesthesia

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Varicose veins

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue