Tricuspid valve dysplasia

Ebstein’s anomaly

Downward displacement of valve leaflets

Minimal

Present, may be severe

Rotation of hinge point of valve leaflets

Absent

Present

Failure of delamination

Present

Present, may be severe

Valve dysplasia

Present

Present

Abnormalities of tension apparatus

Present

Present

Myocardial abnormalities

Present if in association with other abnormalities

Present

Functional component of the right ventricle

Normal

Reduced

Anatomy and function of the systemic ventricle

Normal

Abnormal

Coexistent cardiac abnormalities

Mainly pulmonary valve abnormalities especially pulmonary atresia

Atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries

2.4 Associations

Tricuspid valve dysplasia is often an isolated anomaly without other congenital malformations. There may be family history of abortions or congenital heart defects. Pulmonary valve dysplasia and stenosis is the most common association and can be a serious management problem in the immediate neonatal period when a large persistent arterial duct is present [8].

2.5 Pathophysiology

2.5.1 Clinical Characteristics

2.5.1.1 Foetal Presentation

The majority of cases are detected in the foetal period during routine scanning. Foetal presentation is a predictor of poor outcome [9]. Foetal presentation depends on the severity of the tricuspid regurgitation and the association with other lesions such as pulmonary atresia. Massive right atrial dilatation with progressive enlargement of the right side of the heart is a common feature. Poor prognostic signs are the presence of heart failure (hydrops, ascites, pericardial and pleural effusions and polyhydramnios), tachyarrhythmia, massive right atrial enlargement from severe tricuspid insufficiency and absence of forward flow across the pulmonary valve (functional pulmonary atresia). The size of the right atrium is important in prognosis in this group; significant enlargement of the right heart impacts on foetal lung development with the development of pulmonary hypoplasia [10]. A number of prognostic scores have been developed to predict postnatal outcome such as the Celermajer index and the Simpson-Andrews-Sharland score, and although no single echocardiographic feature is consistent in predicting prognosis, a useful indicator is the flow pattern through the pulmonary artery during the first prenatal scan. Retrograde flow was strongly correlated with foetal or neonatal death, and anterograde flow predicted good outcome [11, 12].

2.5.1.2 Neonatal Presentation

Presentation in the neonatal period in the majority of cases is with right heart failure or cyanosis. Heart failure is a consequence of significant tricuspid regurgitation and right ventricular dysfunction. Cyanosis is a result of right to left shunting across the atrial septum due to severe tricuspid regurgitation.

Initial management in the neonatal period is to employ measures aimed at reducing the pulmonary vascular resistance to encourage forward flow across the pulmonary artery and reduce the amount of tricuspid regurgitation; the use of prostaglandins to maintain ductal patency and thereby improve pulmonary blood flow is encouraged. One needs to be aware however of the risk of developing a circular shunt with blood circulating via the ductus to the pulmonary arteries, through the pulmonary valve and from the right ventricle via the incompetent tricuspid valve to the RA and across the septal defect to the LA and returning to the LV. In these circumstances to stop this spiralling deterioration the prostaglandins would need to be discontinued. When the pulmonary vascular resistance starts falling and signs of pulmonary overcirculation develop, to further stabilise the circulation, ductal ligation may be necessary. Neonatal presentation with heart failure or cyanosis is a poor prognostic feature [13, 14].

Neonates with severe tricuspid regurgitation present early with heart failure and cyanosis. These babies will have a right to left shunt at the atrial level and in some cases may be duct dependant should there be absence of forward flow in the pulmonary artery (functional pulmonary atresia). The degree of tricuspid regurgitation is exacerbated by raised pulmonary artery pressures and the additional association with severe pulmonary hypoplasia. It is often impossible to achieve adequate ventilation. Thus, the cause of death is lung hypoplasia although the primary lesion is cardiac [15].

2.5.1.3 Adult Presentation

Cases of tricuspid valve dysplasia presenting for the first time as adults have been described [16, 17]. Adult presentation is due to increasing exercise intolerance and right heart failure. Many of these patients will have a history of atrial fibrillation related to right atrial dilatation. An important differential diagnosis at this age includes carcinoid disease and rheumatic heart disease. It is also important to exclude infective endocarditis in this patient group. Surgery is possible and is indicated for heart failure resistant to all medical treatment. This is performed by annuloplasty or by mechanical or bioprosthetic valve replacement [17].

2.5.2 ECG and Chest X-Ray Features

Chest X-ray will demonstrate marked cardiomegaly with reduced pulmonary vascularity in those with severe tricuspid regurgitation. The electrocardiogram may show evidence of right atrial and right ventricular enlargement and is relatively nonspecific. In cases where the tricuspid regurgitation is related to intrauterine hypoxia and papillary muscle ischaemia ST segment, depression may be prominent in the anterior precordial leads [18].

2.5.3 Echo Features

Two-dimensional echocardiography has demonstrated good anatomic correlation with the intracardiac anatomy associated with tricuspid valve dysplasia [19, 20]. Two-dimensional echocardiography is currently the primary diagnostic imaging tool used for the diagnosis of Ebstein’s anomaly and TV dysplasia (Fig. 2.1).

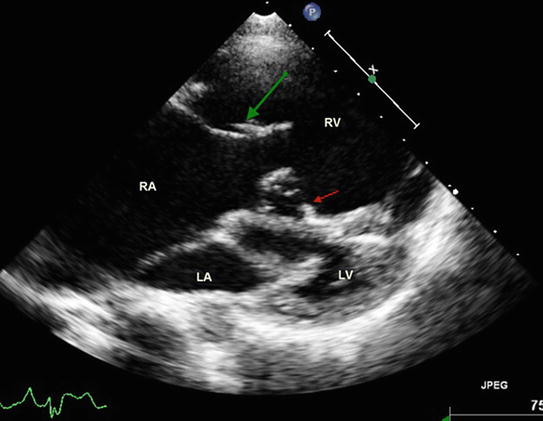

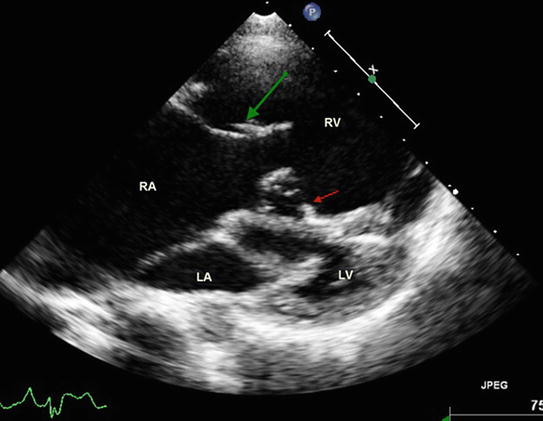

Fig. 2.1

2D transthoracic image reconstructed from a 3D data set illustrating dysplastic anterior ventricle (RV) with dysplastic tricuspid valve. The green arrow points to the large antero-superior leaflet and the red arrows points to the dysplastic septal leaflet with delamination anomaly. Note that both tricuspid and mitral valves open along the long axis of the corresponding ventricles without any rotational changes. RA right atrium, LA left atrium, LV left ventricle

Having said this two-dimensional echocardiography does have limits to the information that it can provide. Three-dimensional echocardiography overcomes this problem by allowing the operator to analyse in vivo valve morphology in a number of planes, thus being able to differentiate more accurately between tricuspid valve dysplasia and Ebstein’s anomaly, i.e. the degree of displacement of the valve leaflets and the rotational abnormality of the valve seen in Ebstein’s. Not only does three-dimensional echocardiography allow the operator to display the image from a clinically useful perspective, i.e. surgeons view, the multiplanar review mode allows the operator to review the image in three infinite orthogonal planes [21, 22] (Figs. 2.2, 2.3, and 2.4).

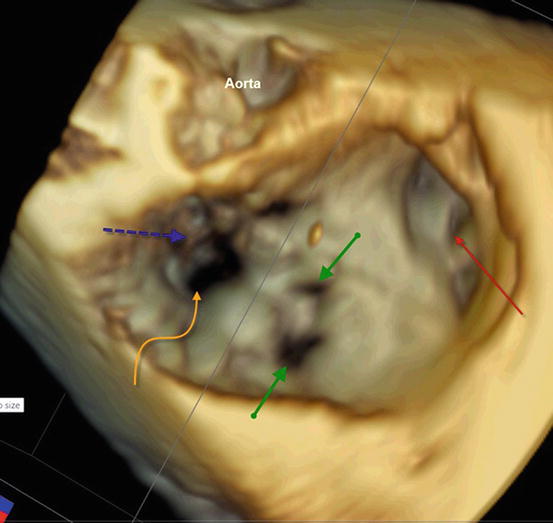

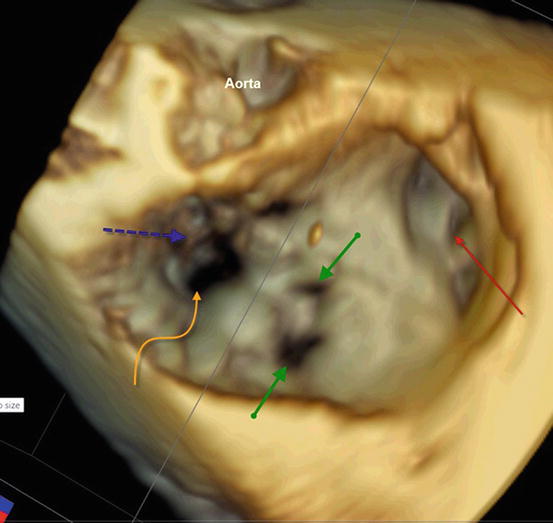

Fig. 2.2

3D imaging of a dysplastic tricuspid valve: view from the right atrium (RA) showing dilated RA and appendage (red arrow), fenestrations in the large antero-superior leaflet (green arrows) and deficient coaptation point (curved yellow arrow) with delamination anomaly of the septal leaflet (blue arrow)

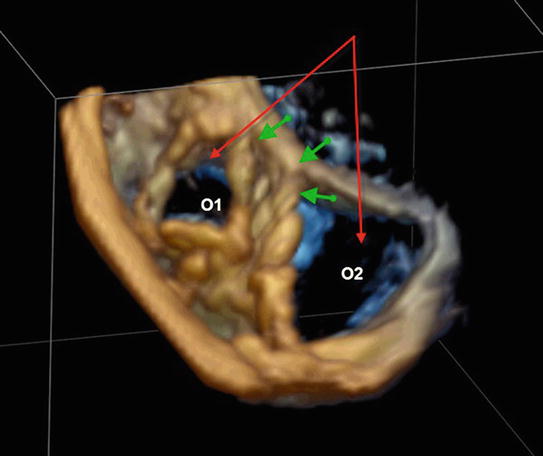

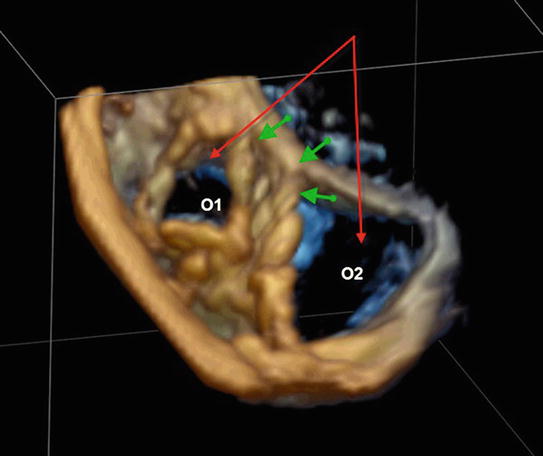

Fig. 2.3

Transthoracic 3D imaging of dysplastic tricuspid valve with formation of two orifices (O1 and O2) due to tethering of a large antero-superior leaflet to the interventricular septum (green arrows). O1 was competent, whereas there was severe regurgitation due to failure of coaptation at O2 (red arrows)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree