Thoracic Sympathectomy (Sympathicotomy)

Seth D. Force

INTRODUCTION

Thoracic sympathectomy has undergone significant change since its initial description over 100 years ago. Originally described utilizing a posterior approach, the procedure has changed over the years from a supraclavicular approach and transaxillary thoracotomy to multiport thoracoscopy and, most recently, single-port thoracoscopy. Indications for a thoracic sympathectomy include the treatment of reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), Raynaud’s Disease, chronic pancreatic pain, and, most commonly, hyperhidrosis. Hyperhidrosis presents as severe sweating of the face, hands, axillary regions, feet, or any combination of these and is present in at approximately 2% of the population.

ANATOMY

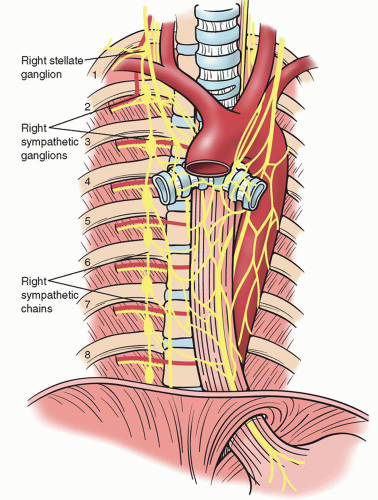

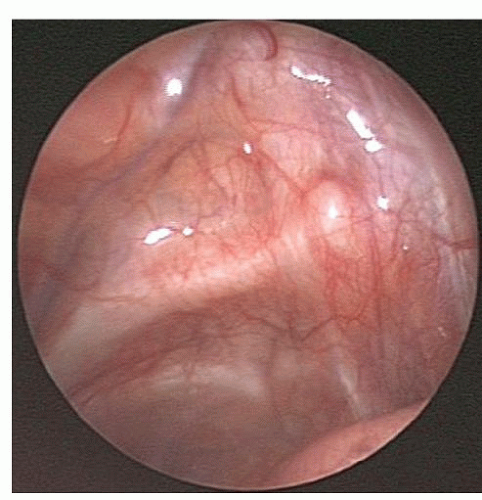

ANATOMYThe thoracic sympathetic chain exists as a paired group of, up to, 12 interconnected ganglia that correspond to each thoracic nerve. The chains lie in either pleural space on the ventral surface of the ribs just lateral to the costo transverse process articulation (Figs. 33.1 and 33.2). The sympathetic chains take a more lateral position as they travel more inferiorly in the chest. Each ganglion lies below the corresponding named rib thus the stellate, or T1 ganglion, lies just below the first rib and is frequently covered by cervicothoracic fat pad (Fig. 33.3). This anatomy, however, is not always constant and in a minority of patients ganglia may be fused or located at or slightly above their corresponding rib. Attention to anatomy is critical for defining the correct level of the desired sympathectomy. The first rib can always be identified by the subclavian artery that courses over it and by the fact that it lacks a corresponding intercostal muscle on its superior border.

Aside from the main sympathetic chain, smaller accessory nerves of Kuntz can be found in up to 60% of patients (Fig. 33.4). These nerves were originally described as only crossing the second rib but, more recently, they have been shown to crossover any of the first four thoracic ribs. Currently, there is some argument as to the role of the Kuntz nerves in pathologic processes such as hyperhidrosis; however, most thoracic surgeons make an attempt to find and transect these nerves.

Various approaches to division of the sympathetic chain have included resection of the individual ganglia as well as division of the interganglionic nerve trunk. This difference in the technique has led to confusion and misnomers when surgeons discuss the intended procedure in the literature and with patients. To clear this confusion, a consensus has been reached, which considers a sympathectomy, to be excision of a ganglion, or ganglia, over a specific rib or ribs (designated by the letter G/level of treatment). A sympathicotomy, on the other hand, consists of division of the sympathetic chain without removal of ganglia (designated by the letter R/level of treatment). This is the most common practice for conditions such as hyperhidrosis even though most studies improperly call this a sympathectomy. Current nomenclature defines the level of sympathicotomy at the corresponding rib where division of the nerve chain occurs. Thus, an R3 sympathicotomy would be defined as the division of the sympathetic chain over the third rib.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION/NONSURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF THE HYPERHIDROSIS PATIENT

Preoperative Evaluation

Hyperhidrosis is defined as the excess production of sweat by the eccrine glands. Although specific volumes of sweat production have been suggested, to define hyperhidrosis, the typical patient has visibly moist hands or axillae and often has sweat dripping from these areas. A family history of hyperhidrosis can be found in up to 50% of patients and, although by definition patients must have symptoms for over 6 months, most patients have had significant symptoms for years.

Hyperhidrosis can be further separated in primary/idiopathic or secondary. Primary hyperhidrosis is usually limited to the face, hands, axillae, and feet with palmar-plantar sweating being the most common variant. Secondary hyperhidrosis can be localized or diffuse and is due to various conditions ranging from hyperthyroidism to neurologic injury and side effects from medications. A thorough history and physical examination is required for all patients being evaluated for increased sweating since surgical correction is considered only for patients with primary hyperhidrosis.

Nonsurgical Management

Nonsurgical management of primary hyperhidrosis includes the use of oral and topical agents, the application of botulinum toxin (Botox), and the use of electrical currents known as iontophoresis. Oral agents used are anticholinergic drugs and include glycopyrrolate, oxybutynin, and propantheline. These drugs work by muscarinic receptor blockade but have the disadvantage that their action is not specific to the areas of increased sweating. Common side effects include dry mouth and eyes, blurred vision, and urinary retention.

Iontophoresis involves the use of an electrical current that flows through a water bath where hands or feet are placed. Clinical success rates can be as high as 80%, and the treatment effects can last anywhere from 2 months to a year. Side effects of iontophoresis are mild and usually well tolerated. Topical agents usually involve an aluminum-based chemical ointment or cream, which can be applied to hands, feet, or axillary regions. Results of topical agents are variable and

side effects are usually related to local skin reactions. Botulinum toxin injections for palmar, axillary, and pedal hyperhidrosis have also been used with good success rates but this treatment is not always well tolerated by patients and requires repeated injections over time.

side effects are usually related to local skin reactions. Botulinum toxin injections for palmar, axillary, and pedal hyperhidrosis have also been used with good success rates but this treatment is not always well tolerated by patients and requires repeated injections over time.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree