CHAPTER 3

The Tools

“One who knows strengths and weaknesses of different tools lowers the risk and succeeds often.”

—Anonymous

Percutaneous Access Needles

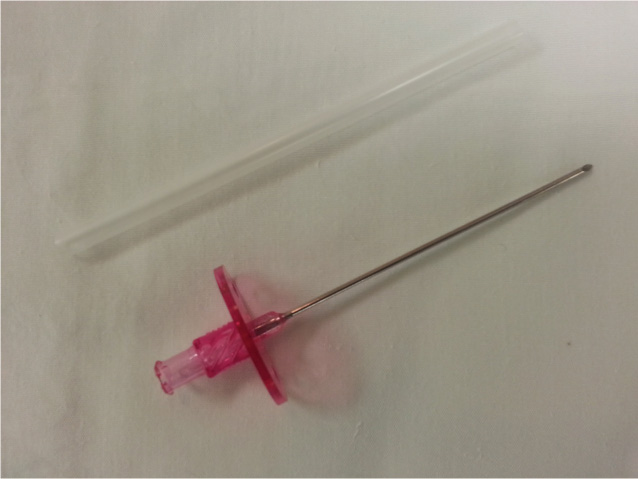

There are two major types of access needle design: the standard disposable Seldinger needle and the standard direct front-wall needle. A standard Seldinger-type access needle has a blunted bevel and is accompanied by a stylet. A standard direct front-wall needle has a sharper bevel angle and does not have the second component such as a stylet. It may or may not have a baseplate hub (Figure 3.1).

FIGURE 3.1A standard direct front-wall needle (Cook Medical, Inc.) has a sharper bevel angle than the Seldinger-type needle (not shown).

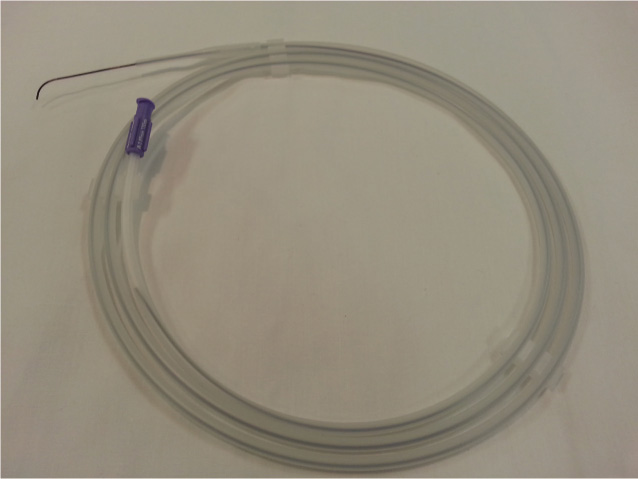

The 18-gauge, 0.049-inch diameter needle, up to 3 inches in length, allows passage of a flexible 0.035-inch guidewire with a 3 mm “J” tip. The major advantage of the direct front-wall needle is the ability to decrease the risk of site bleeding and hematoma formation as a result of posterior vessel wall puncture. This is a major advantage when cardiac catheterization is performed in a fully anticoagulated patient. A direct front-wall needle attached to a 12-mL syringe is used when attempting to establish central venous access. In situations such as a small, calcified, tortuous femoral vessel or the use of an anticoagulant, a smaller needle may be preferred to reduce the risk of access complications. The Micropuncture Kit (Cook Medical, Inc., Bloomington, IN) includes a 21-gauge needle and a 4-Fr (1 Fr is 0.33 mm) sheath (Figure 3.2).

FIGURE 3.2The Micropuncture Kit (Angiodynamics Inc., Cambridge, UK) with a 21-gauge needle and a 4-Fr sheath is shown.

Although the smaller needle reduces the size of the arterial hole by more than 50%, there is no clear evidence that the Micropuncture Kit reduces vascular complications.1,2 In high-risk procedures with difficult single arterial or venous access, percutaneous access can be achieved by a specific ultrasound-guided needle.3,4

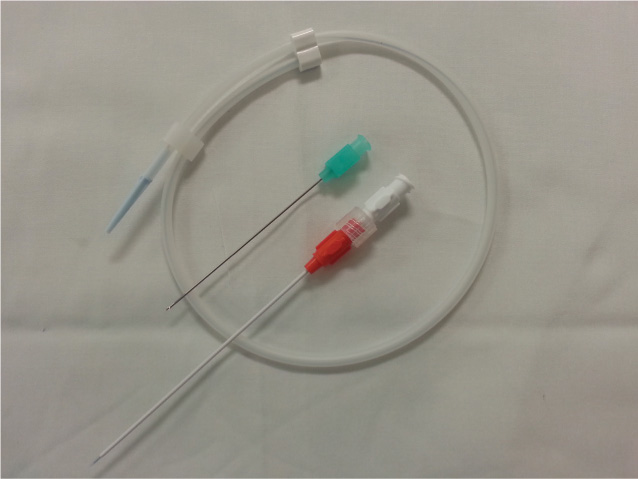

Guidewires

The guidewire is the cornerstone of Seldinger’s idea of percutaneous access of the blood vessel.5 Basic guidewires differ in shape (straight versus J-tipped), diameter, length, and structure. Most invasive cardiologists use flexible 0.035- or 0.038-inch J-tip guidewires when obtaining vascular access since it decreases the risk of vessel dissection (Figure 3.3).

FIGURE 3.3Flexible 0.035- or 0.038-inch J-tip guidewire (Cook Medical, Inc.) are used to decrease the risk of vessel dissection.

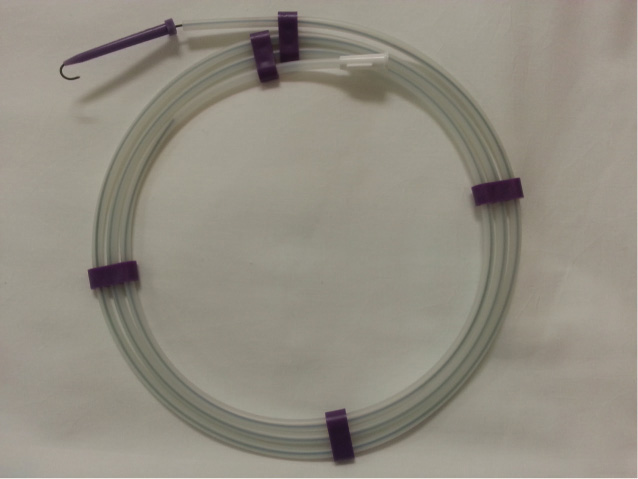

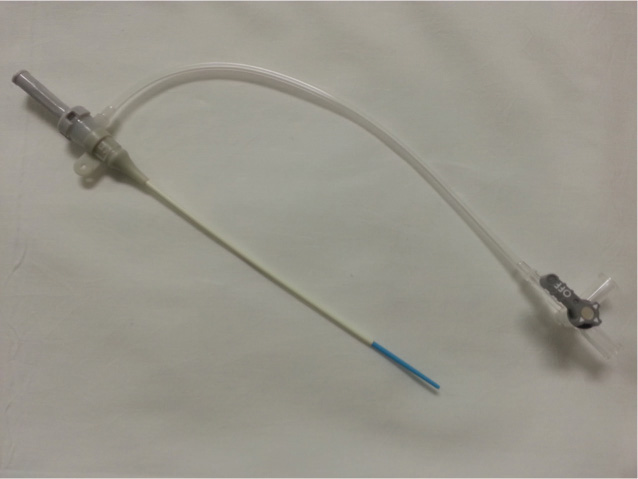

The 0.021- or 0.025-inch straight-tip guidewires are used primarily when obtaining radial arterial access, or when attempting to stiffen the balloon-tipped pulmonary artery catheter. The straight, soft-tipped wires are used in crossing severely stenosed aortic valves. The decision on length of the guidewire, short (30–45 cm) versus long (120–150 cm), is made based on the type and length of the sheath to be placed. The extra-long guidewires’ (250–300 cm) primary use is to avoid repeatedly negotiating and crossing tortuous and/or diseased vessels during the catheter exchange process. The general structure of most guidewires is similar: a flexible, distal spring coil, a regular or gradually tapered, movable central core, usually made from stainless steel, and an external hydrophilic coating to decrease thrombogenicity and friction. In order to navigate through the severely diseased and/or tortuous peripheral blood vessels, a Zipwire—a specific “slippery” hydrophilic guidewire with good steerability and torque response—is used (Figure 3.4).

Some operators use a stopcock device, locked at the distal end of the wire, to improve handling and maneuvering of these wires. The use of “slippery” wires when obtaining vascular access is not recommended due to the potential for the wire to slip through the access needle and be lost in the circulation. In addition, there is a potential problem with shearing off the polyurethane cover of the slippery wire by the tip of the access needle.

Vascular Sheaths and Dilators

Vascular sheaths are major elements of a cardiac catheterization procedure (Figure 3.5).6

FIGURE 3.5Terumo Pinnacle Sheath (Terumo Medical, Elkton, MD) is one type of vascular sheath used in cardiac catheterization.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree