The Heart Valves

Sticking and Leaking Valves

The valves you read about in Chapter 2 are made of thin flaps of living tissue: they can become diseased like any other tissue. The effect of disease on the valves will take one of two forms.

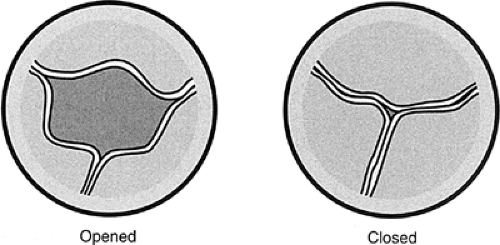

The word stenosis refers to an abnormal narrowing of any kind of passage or opening. Stenosis of a valve means that the valve can’t swing open as widely as it should. Sometimes this happens because the valve flaps are stuck together by adhesions—that is, by scar tissue that forms after an inflammation (Fig. 9-1).

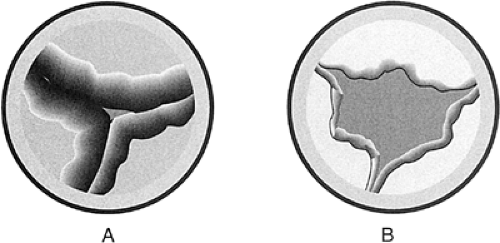

Sometimes the flaps turn into heavy, rigid masses of scar tissue that are so stiff they can’t swing apart normally (Fig. 9-2A). In either case, the blood is forced through an abnormally small orifice, like a large river running through a narrow canyon. Regurgitation, of course, means “leaking.” When a physician says that a valve regurgitates, he or she could just as well say it leaks, but that wouldn’t sound nearly as impressive. Normal valve flaps meet tightly at the edges, like perfectly milled doors. The blood can’t go back into the chamber it came out of, so it has to move forward.

Imagine that a vandal went down the meeting edges of our two perfectly milled doors with a rasp file and a saw, cutting gouges and holes, so that when the door swung shut the wind whistled back through. That’s exactly what disease processes can do to the edges of the valves. They can be scarred and gouged out of shape, so that when they swing shut there are holes and gaps that let the blood leak back into the chamber it just came out of (Fig. 9-2B). It’s better to consider this subject one valve at a time.

Aortic Stenosis

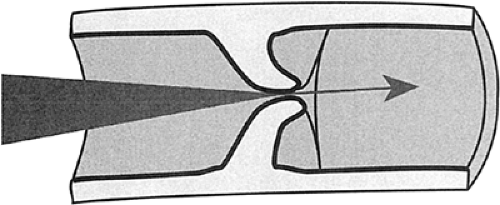

This is the most dangerous of all valve lesions: it often leads to sudden death. Stenosis of the aortic valve was formerly caused by the scarring that follows rheumatic fever. This disease is now rare in the Western world and the great majority of cases of aortic stenosis at this time are the result of chalky degeneration, or sclerosis, of the aortic valve. The valve flaps become heavy and rigid and the valve opening may be no more

than a slit. This type of sclerotic, or rigid-degenerative, disease is almost always seen in older patients (Fig. 9-3).

than a slit. This type of sclerotic, or rigid-degenerative, disease is almost always seen in older patients (Fig. 9-3).

When the heart has to force the entire blood supply of the body through a tiny opening, there are a number of consequences, all bad.

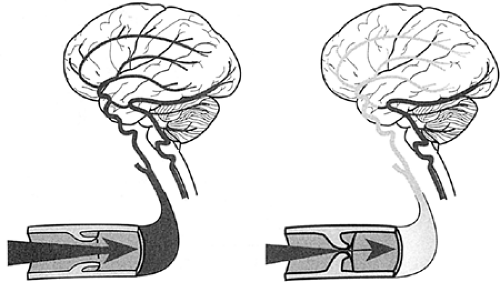

The blood supply to the brain is cut down. The patient will often become dizzy, or will actually faint, especially when exercising (Fig. 9-4).

The muscle of the left ventricle has to work against an enormous load. The muscle wall will enlarge for a time, but finally the pumping action of the ventricle will fail. Congestive heart failure follows swiftly (see Fig. 7-5 in Chap. 7).

The enormous muscle mass of the ventricle outruns its own coronary blood supply. The patient will begin to feel anginal pain.

When aortic stenosis begins to produce any of these symptoms, there is a 50% risk of sudden death within 2 years. Surgical replacement of the valve is urgent (Fig. 9-5). The results of surgery are very good, and the great majority of patients recover cardiac function to a large extent.

This excellent outcome arises from the fact that aortic stenosis puts a “pressure load” on the heart muscle, which hypertrophies, or thickens, in response. When the pressure load is removed, the heart muscle can revert to a normal state to a surprising degree.

Aortic Regurgitation

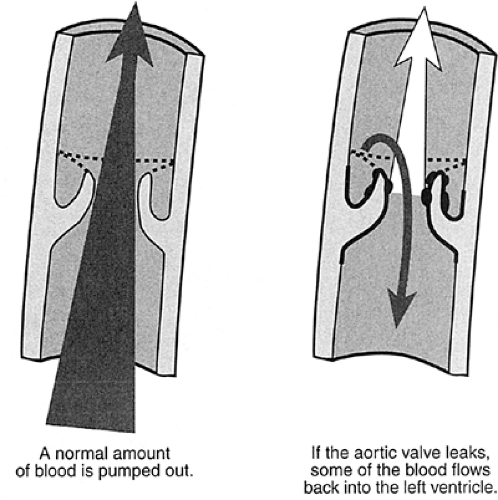

When the aortic valve leaks blood back into the left ventricle, the chamber has to work harder than normal. It has to pump the blood that leaked back out again together with the usual volume of blood it would have pumped anyway.

The seriousness of aortic regurgitation depends entirely on the volume of blood that leaks. If it’s only one-half teaspoon (about 2 cc), for example, the patient can lead a normal life with a normal life expectancy. If it’s a tablespoonful (16 cc), the heart will be overloaded. The patient will go into congestive heart failure and will die if the valve isn’t replaced surgically (Fig. 9-6).

The only effect of aortic regurgitation is to overload the left ventricle and produce congestive heart failure. The only symptom of aortic regurgitation is shortness of breath.

Important warning about aortic regurgitation: If a serious leak goes on too long, the ventricle is stretched past the point of no return. Changes take place in the heart muscle so that it never regains normal function. Even after the valve is replaced surgically, some patients will die of progressive heart failure. This is because there has been a volume load imposed on the left ventricle by the mass of blood leaking back through the valve and the muscle is actually stretched in a way that damages the cells so that they never recover. Timing of valve replacement in aortic regurgitation is one of the most difficult decisions in cardiology. Measurement of the size of the left ventricle by echocardiography is one of the most important tests in helping the cardiologist make this decision.

Mitral Stenosis

This is always caused by the scarring of rheumatic fever. Since rheumatic fever is rare in the Western world, this valve lesion is becoming uncommon, but it still turns up as the result of rheumatic fever in earlier life. The edges of the valve flaps are stuck together with adhesions, so that the valve opening is sometimes no bigger than a ballpoint pen. When this happens, the blood backs up into the lungs and the changes of

congestive heart failure follow. In the later stages, the valve flaps may become heavy with scar tissue, so that they have the consistency of chalk or wood (Fig. 9-7).

congestive heart failure follow. In the later stages, the valve flaps may become heavy with scar tissue, so that they have the consistency of chalk or wood (Fig. 9-7).

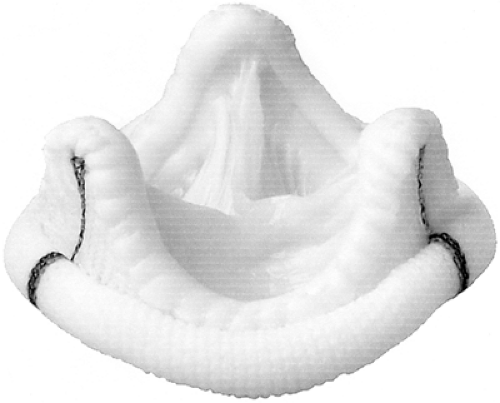

FIGURE 9-7 Rheumatic heart disease affecting the mitral valve. The two flaps of the mitral valve occupy the right-hand two thirds of the picture: they are thickened and white as a result of scarring and subsequent calcification. (Courtesy of Dr. Richard E. Sobonya, Pathology Department, University of Arizona Medical Center.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|