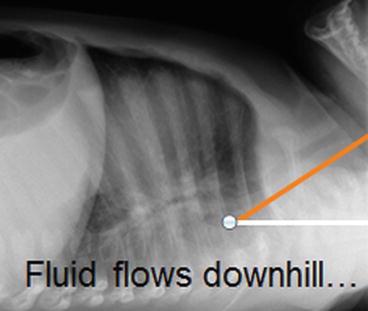

Fig. 1.1

Flexible and rigid instruments approach the larynx from very different perspectives. A rigid instrument necessarily elevates the hyoid and tongue base, lifting and distorting the larynx, while at the same time allowing more detailed anatomic evaluation as well as manipulation of the tissues under direct vision. The flexible instrument, on the other hand, approaches from behind, and is much more suitable for evaluation of laryngeal dynamics. When there is any suspicion of posterior laryngeal pathology (laryngoesophageal cleft, for example) both instruments may need to be employed in order to obtain a full understanding of the laryngeal anatomy and dynamics. (a) Lateral radiograph showing the path taken by rigid and flexible instruments. Note the elevation of the hyoid and tongue base by the rigid instrument and the angle of approach to the larynx by both instruments (this is not the same patient as in b and c). (b) The larynx of a child with a history of inspiratory stridor, seen by a flexible instrument. There is no traction on the larynx, and in this view, the mucosa overlying the arytenoid cartilages completely obscures the view of the glottis, and produces significant inspiratory obstruction. (c) The same larynx as seen by a rigid instrument. The larynx is being elevated by a rigid laryngoscope. The mucosa, which through the flexible instrument looked redundant and possibly edematous, now looks anatomically normal, and there is no obvious obstruction

Sedation, Anesthesia, and Airway Management for Flexible Bronchoscopy in Children

It is possible to examine a child’s airway without sedation. The most common setting for this approach is a simple evaluation of the nasopharyngeal airway and larynx in an office setting, including the endoscopic assessment of swallowing. Most children do not like this, and it may be difficult for the operator as well. However, full assessment of vocal cord function may require this approach. When the bronchoscope needs to be passed beyond the glottis, it is much wiser and safer to provide sedation for pediatric patients.

In the early days of pediatric flexible bronchoscopy, most procedures were done with sedation provided by the bronchoscopist. Today, most procedures are performed with the aid of an anesthesiologist, and this is very appropriate, in order to enhance safety; it also enables the use of agents that are generally restricted to use by anesthesiologists and can provide a more smooth and comfortable evaluation. However, choice of the wrong technique for sedation is one of the easiest ways to achieve the wrong diagnosis. Sedation that is too deep may mask dynamic pathology, and sedation that is not sufficiently deep may increase the risk of complications and possibly lead to termination of the procedure before the answer has been obtained. It is vitally important that the bronchoscopist and the person responsible for the sedation and monitoring of the child both have an adequate understanding of the purpose of the procedure and that they communicate effectively before, during, and after the procedure. It is often useful to change the level of sedation during the course of an examination. For example, a deeper level of sedation at the beginning may facilitate the anatomic evaluation and collection of specimens, while lightening the sedation near the end of the procedure may facilitate documentation of abnormal airway dynamics.

The precise techniques utilized for sedation of children for bronchoscopic procedures is as much a matter of personal preference as anything, as long as the patient is safe and the goals of the procedure are adequately met. Mask induction followed by establishment of intravenous access and maintenance with a short-acting parenteral drug can be a very effective technique.

Pediatric bronchoscopy is certainly among the most challenging tasks an anesthesiologist is called upon to perform. As bronchoscopists, we violate virtually every principle that anesthesiologists hold near and dear: we want control of the airway, we want to see the airway obstruct (at least, long enough for us to be able to understand why the child’s airway is obstructing), and we often want to see the child cough (so that we can see lower airway dynamics). Modern bronchoscopes employ digital display, and it is very helpful for the anesthesiologist to be able to visualize what the bronchoscopist is seeing. This does not in itself suffice for effective communication between the bronchoscopist and the anesthesiologist.

Airway management can be one of the most contentious issues between the anesthesiologist and the bronchoscopist. Typically, the child is placed under light anesthesia so that spontaneous ventilation is maintained, and an oral airway is placed. The bronchoscope is then inserted through one nostril. However, the presence of the oral airway distorts the anatomy, and it often needs to be removed, at least temporarily, while the upper airway anatomy and dynamics are assessed. Once this is accomplished, the oral airway can be reinserted and the bronchoscope directed into the lower airways. The bronchoscopist should evaluate the position of the oral airway (in many cases, the oral airway may actually push the posterior tongue over the larynx, obstructing, rather than opening, the airway). It is quite effective (so long as the patient is breathing spontaneously) to insert an endotracheal tube into the oral airway to provide for delivery of oxygen and anesthetic gas directly to the larynx (Fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.2

Placement of a shortened RAE tube into the oral airway allows insufflation of oxygen and anesthetic gas and does not obstruct the space above the patient’s face (which can interfere with manipulation of the flexible bronchoscope)

Many bronchoscopists and anesthesiologists routinely perform their procedures through a laryngeal mask airway (LMA). While this is easy, and allows positive pressure ventilation from start to finish, there are many reasons to condemn this as a routine practice. An LMA completely bypasses the nasopharyngeal airway, and many diagnoses will be missed. The LMA also presses against the post-cricoid region of the larynx, and can interfere with vocal cord motion; it also can put downward traction on the post-cricoid mucosa, making it impossible to adequately diagnose some forms of laryngomalacia (see Figs. 1.3 and 1.4). An LMA does not prevent laryngospasm or even, necessarily, aspiration of oral secretions. When positive pressure support is given through the LMA, it can be impossible to adequately evaluate tracheomalacia or bronchomalacia. On the other hand, there are clearly some circumstances where the use of an LMA may be appropriate and effective; these primarily involve situations in which there is no clinical concern about the upper airway anatomy or dynamics, and the child may be too small to utilize an endotracheal tube with the flexible bronchoscope. However, as the 2.8 mm flexible bronchoscope can readily and safely be used through a 3.5 mm endotracheal tube, there are relatively few situations in which this may be the technique of choice. If the bronchoscopist feels strongly that an LMA is essential to safe and effective evaluation of the lower airways, then very serious consideration should be given to an evaluation of the upper airways without the presence of the LMA. If this is done as the last step in the global procedure, then there will be less chance for contamination of the BAL specimens with upper airway secretions, and can be done as the patient recovers from the sedation.

Fig. 1.3

How an LMA can lead to erroneous diagnoses. The first panel shows the larynx of a child with MPS II with an LMA in place. The patient has a history of significant stridor, but through the LMA, the larynx does not look too abnormal (and no stridor could be heard). The LMA was removed; the second panel shows hypopharyngeal collapse (this photo does not show the full extent of the collapse, which was complete). The third panel shows the larynx with mandibular lift; the mucosa overlying the post-cricoid area is redundant, and the arytenoids are large. The final panel shows the dramatic inspiratory prolapse of the arytenoid mucosa when mandibular lift was relaxed. The LMA did not allow evaluation of the supraglottic airway, and the traction on the post-cricoid mucosa created by the tip of the LMA in the upper esophagus made it impossible to appreciate the laryngomalacia

Fig. 1.4

The laryngeal mask airway can be useful, but it is inappropriate to employ the device for every procedure as the primary technique for airway management

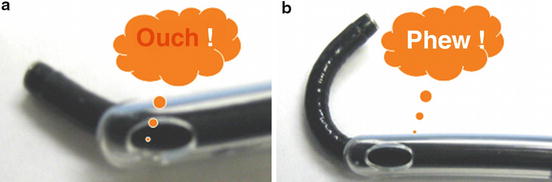

It is often necessary or desirable to perform a flexible bronchoscopy through an endotracheal tube. Care must be taken to ensure that the tube is adequately lubricated (otherwise, manipulation of the bronchoscope may be difficult, or the bronchoscope may be physically damaged). Care must also be taken to ensure that the tip of the flexible bronchoscope extends far enough beyond the end of the endotracheal (or tracheostomy) tube before the tip is flexed; attempting to flex the tip of the scope while the bending segment of the instrument is still within the confines of the tube can result in breaking the control wires (Fig. 1.5).

Fig. 1.5

Care must be taken when passing a flexible bronchoscope through an artificial airway (endotracheal or tracheostomy tube) to not flex the tip of the instrument until the bending segment has passed beyond the end of the tube. Otherwise, the bronchoscope can be damaged

A 2.8 mm bronchoscope can be safely utilized through a tube that is only 3.5 mm in diameter. However, this will result in a high level of obstruction to airflow through the tube. It is much easier to force air through the tube and into the lung than for the air to passively escape, and if there is not a sufficient leak around the outside of the tube, a very high level of airway pressure (“inadvertent PEEP”) can develop, even leading to a tension pneumothorax. Conversely, excessive suctioning when the instrument is passed through a relatively small tube can result in a dramatic decrease in the patient’s functional residual capacity and rather impressive oxygen desaturation can result. This is generally easily managed, however, by removing the bronchoscope and applying positive pressure ventilation through the endotracheal or tracheostomy tube (an alveolar recruitment maneuver is often most beneficial).

Techniques for Flexible Bronchoscopy

In the majority of diagnostic flexible bronchoscopies, it is desirable to obtain a specimen (bronchoalveolar lavage “BAL”) for cytologic and microbiologic analysis. This specimen should be representative of the state of the lungs prior to the procedure—it is therefore important to minimize the risk of aspiration of oral secretions before the specimen can be obtained. The nose and hypopharynx should be gently suctioned prior to inserting the bronchoscope. Continuous insufflation of oxygen (~2 L/min) through the suction channel of the bronchoscope during passage through the nose and to the larynx can minimize contamination of the suction channel. Application of topical lidocaine to the larynx, while essential, also immediately leads to the risk of aspiration. Employing a small volume (0.5 mL) can help minimize this. However, when a patient is lying supine, the carina is at an approximately 30° downhill position from the larynx, and it is very common to visualize secretions draining from the mouth towards the carina as the bronchoscope is initially inserted. Suctioning of these secretions will of course contaminate the instrument and therefore the subsequent specimen, as will delay in obtaining the BAL specimen (Fig. 1.6)