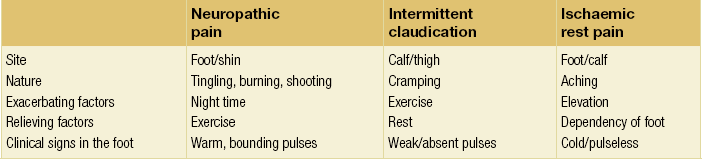

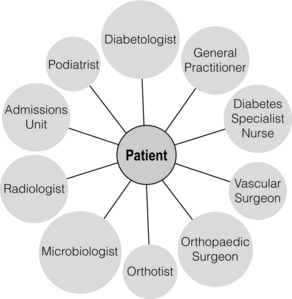

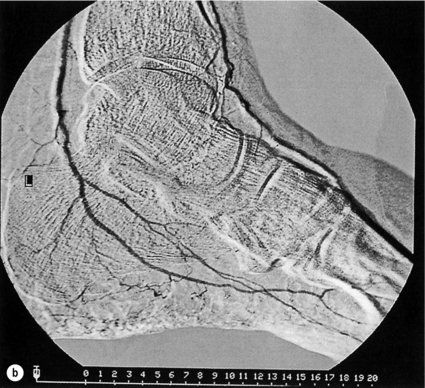

5 Foot problems are one of the most common complications of diabetes, with 15% of patients developing a foot ulcer in their lifetime.1 Foot complications account for more hospital admissions than other complications of diabetes2 and are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality.3 The main aetiological factors in foot ulcer development are peripheral neuropathy and peripheral vascular disease, either alone or in combination with biomechanical abnormalities and susceptibility to infection. Diabetic foot problems can include a wide range of conditions, including peripheral neuropathy and associated neuropathic pain, peripheral vascular disease, ulceration, osteomyelitis, Charcot neuroarthropathy and, ultimately, lower limb amputation. People with diabetes are eight to 24 times more likely than those without diabetes to have a lower limb amputation,4 and it is suggested that about 85% of those amputations could be avoided by early detection and involvement of a specialist foot team.5 Patients with diabetes often exhibit multiple complications of their diabetes, including retinopathy, nephropathy and ischaemic heart disease, and as such their care can be complicated and require a multidisciplinary team of physicians, surgeons and allied health professionals. The estimated global prevalence of diabetes in 2010 was 285 million, expected to rise to 438 million by 2030.6 In the UK, in 2011, there were 2.9 million people diagnosed with diabetes,7 a figure that will rise to more than 4 million by 2025,6 and as such the prevalence and incidence of foot ulceration are likely to increase also. There have been a number of population studies looking at incidence of foot ulceration in patients with diabetes, in various community-based populations. In a 2002 study from the north-west of England, the annual incidence of foot ulceration was reported as 2.2% among 10 000 community-based patients with type 2 diabetes.8 In the Wisconsin study, the 4-year incidence of ulcers in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes was 9.5% and 10.5%, respectively.9 A later study from the USA showed that 5.8% of patients followed up over 3 years developed a foot ulcer, nearly 2% per year.10 When considering the aetiology of foot ulcers, 45–60% of ulcers are neuropathic, around 10% purely ischaemic and the remaining 25–45% of ulcers are of mixed neuroischaemic origin. A study of all patients attending a foot clinic over a 7-year period showed a slight reduction in the proportion of neuropathic ulcers, at 36%, with 52.3% neuroischaemic and 11.7% ischaemic.11 This may represent a changing pattern of presentation of diabetic foot ulcers, as a result of patient education, and the introduction of multidisciplinary foot clinics; further research is needed to establish if this is the case. In 2005, the International Diabetes Federation wrote a position statement on care of the diabetic foot, which states that, every 30 seconds, a leg is lost to diabetes somewhere in the world.12 Evidence suggests that 100 patients with diabetes per week lose a toe, foot or lower limb,13 and up to 70% of patients die within 5 years of having an amputation due to diabetes.14 There are a number of manifestations of diabetic neuropathy, from simple mononeuropathies to complex polyneuropathies with autonomic involvement. In the lower limbs, distal sensory polyneuropathy is the commonest presentation, but motor and autonomic fibres can also be involved. The development of neuropathy is linked to poor glycaemic control over many years, and therefore increases in frequency with both duration of diabetes and advancing age. Estimates of the prevalence of neuropathy vary due to differences in diagnostic criteria and populations. A number of studies have indicated a prevalence of approximately 30% among patients with diabetes in hospital, with lower rates closer to 20% in population-based samples;16 these figures are likely to be higher when examining an elderly population, and may be as high as 50%. Regular foot examination is essential to identify when neuropathy is present, so that appropriate education can be instituted and treatment given where appropriate to prevent complications resulting from loss of protective sensation. Unless proper foot examination is carried out, the diagnosis can be missed in a significant number of patients.17 Not every patient with diabetic neuropathy will describe symptoms; indeed, they may be completely unaware of their marked sensory loss, which can therefore only be detected by regular screening of the asymptomatic patient with diabetes. Over time, as the neuropathy evolves, patients may experience symptoms. These can be extremely painful, such as burning, altered temperature perception, paraesthesia or allodynia (touch perceived as a painful stimulus), or may be so-called negative symptoms, such as numbness or deadness in the limb. Symptoms of neuropathy can be differentiated from intermittent claudication more easily by the nocturnal exacerbations, lack of relationship to exercise and location of symptoms (Table 5.1). Coexistent autonomic neuropathy can reduce sweating in the skin and open arteriovenous shunts, leading to increased blood flow to the leg.18 The neuropathic foot is therefore typically warm with bounding pulses and has dry, sometimes cracked, skin. Motor neuropathy mainly affects the intrinsic muscles of the foot (as they are most distal) and can lead to wasting (guttering between the metatarsals) and altered foot shape, with clawed toes and prominent metatarsal heads. This, in turn, increases the risk from unperceived external trauma (e.g. ill-fitting shoes), repetitive painless injury to high-pressure areas under the metatarsal heads when walking, and easy access for infection through the dry cracked skin. Early neuropathy can be suggested by callus formation on weight-bearing areas. Neuropathy is responsible for a high proportion of foot ulcers; in the Eurodiale study, which looked at 1232 patients across 14 European centres, peripheral neuropathy was present in 86% of patients undergoing treatment for foot ulcers.19 Atherosclerotic vascular disease is probably present (at least in a subclinical form) in all patients with long-duration of diabetes.24 Patients with diabetes often have risk factors for peripheral arterial disease, including hypertension, hyperlipidaemia or smoking. The distribution of vascular disease in the lower limb is thought to be different in diabetes, with more frequent involvement of vessels below the knee. One study of patients referred for angiography showed no difference in proximal disease (iliac, femoropopliteal vessels) but distal disease (calf vessels) was twice as high in patients with diabetes as those without.26 Disease was also more commonly found in multiple locations within the vasculature, and stenoses may also be present in collateral vessels (Fig. 5.1). Figure 5.1 Typical distribution of atherosclerosis affecting the popliteal trifurcation and tibial arteries (a). The distal profunda is also affected (b), which reduces the ability for collaterals to develop around a superficial femoral occlusion. The difficulties posed by the distribution may be further complicated by a reduced ability to develop collateral supply, but despite these problems revascularisation procedures are frequently successful, although a more distal anastomosis may be required. Comparative studies have shown similar long-term outcomes of revascularisation for patients with and without diabetes,27 and diabetes does not have a significant negative impact on distal revascularisation.28 Patients with diabetes and peripheral vascular disease may develop intermittent claudication, but often this is absent, due to coexistent diabetes-related peripheral neuropathy. The first clinical presentation may be ischaemic foot ulceration.24 Typically, the ischaemic ulceration is at the ends of the toes, and in the absence of neuropathy can be painful. The foot is usually cool with absent pulses, but the presence of warmth in a neuroischaemic foot with swelling may suggest underlying deep infection or Charcot neuroarthropathy. The most helpful non-invasive investigation is measurement of the ankle–brachial pressure index (ABPI).29 A combination of a history of calf pain on walking, absent peripheral pulses and an ABPI of less than 0.9 predicts the presence of peripheral arterial disease with 95% sensitivity and specificity.30 ABPI may be falsely elevated (>1.3) with calcification of blood vessel wall, a phenomenon frequently seen in patients with diabetic neuropathy (Fig. 5.2). In this situation, the Doppler waveform seems useful, as loss of the normal triphasic waveform indicates vascular disease. Transcutaneous oxygen tension (measured by an electrode placed on the foot) accurately reflects skin oxygenation and can be used to determine the severity of ischaemia and the likelihood that an ischaemic ulcer will heal.31 Despite advances in non-invasive investigations, arteriography (which should include the pedal arteries) remains the gold standard for both diagnosis and planning of treatment. Magnetic resonance (MR) is the modality of choice for arteriography in patients with diabetes as it avoids the risk of nephropathy and metabolic acidosis associated with the use of iodinated contrast (see Chapter 3 for medical management). Figure 5.2 Calcification of the posterior tibial, anterior tibial and dorsalis pedis arteries in a patient with diabetes (a). The calcification is in the media and may falsely elevate Doppler pressures and make pulses difficult to palpate. However, good arterial flow may still be present (b). The most important cause of foot ulceration is loss of protective pain sensation, permitting ‘painless’ repetitive trauma and tissue injury. Vertical pressure applied to the plantar surfaces of the feet during standing when walking can predispose to ulceration. Plantar pressures can be measured by a number of methods, both dynamic and static. Patients with peripheral neuropathy and particularly patients with foot ulcers have high plantar pressures, although high pressures alone in the absence of insensitivity do not lead to ulceration. Frykberg et al.32 used an F-scan pressure mat system, and identified patients at risk of ulceration with foot pressures >6 kg/cm2. Stacpoole-Shea et al.33 studied a Pedar in-shoe pressure analysis system, and demonstrated its ability to predict potential sites for foot ulceration with a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 69%. Neuropathy and altered proprioception, and small muscle wasting can, in themselves, lead to alteration of the foot architecture and shape, resulting in clawing of the toes, prominent metatarsal heads and a high arch, all of which result in changes in foot pressures.34 To some extent, this can be reviewed clinically and raises suggestions as to where ulcers are likely to occur on the foot. The more severe deformities associated with Charcot neuroarthropathy, with joint dislocation and bony deformities, can also result in increased foot pressures and subsequent ulceration. Limited joint mobility is a further contributing factor to elevated plantar pressures. Chronic hyperglycaemia results in glycosylation of proteins and, when collagen is involved, the collagen bundles become thickened and cross-linked. This results in thick, tight, waxy skin and restriction of joint movement. Limited joint mobility of the subtalar joint alters the mechanics of walking and is strongly associated with high plantar pressures.35 Neuropathy alone does not lead to spontaneous ulceration, but requires trauma in the context of insensitivity to result in tissue damage. Trauma can be a single event, like standing on a nail, but more frequently involves repeated minor trauma, such as an unperceived shoe rubbing to the toes, or increased pressure beneath the metatarsal heads during walking. As mentioned above, it is possible to measure plantar pressures, and a prospective study showed that 28% of patients with high foot pressures developed a foot ulcer during a 30-month follow-up period, with ulcers occurring in those with neuropathy and high foot pressures.36 The presence of callus (produced in response to pressure) may exacerbate the problem by acting as a foreign body, thereby increasing pressure further.37 Removal of callus significantly reduces foot pressures,38 and should be done regularly by an experienced podiatrist. The accurate measurement of foot pressures requires sophisticated and often expensive systems, which are currently only available in specialist centres. However, clinical examination that inspects foot shape and identifies the presence of callus provides very valuable information, which can be used to select patients in need of pressure relief (see management section). Footwear should also be inspected as part of this assessment.15 Indeed, the presence of callus may, in some ways, be superior to pressure measurement, as it results not only from vertical pressure, but also from shear forces, which currently cannot be measured. The presence of haemorrhage into callus should be seen as a pre-ulcerative phenomenon and requires urgent attention. The management of diabetic foot problems requires input from a number of different healthcare professionals (Fig. 5.3), and evidence strongly suggests that specialist diabetic foot clinics can significantly reduce ulceration and amputation rates. One retrospective study showed a 75% reduction in major amputation after introduction of a multidisciplinary foot clinic and improved facilities for revascularisation of ischaemic limbs.39 Care of patients with diabetes who develop foot ulcers should take place in a specialist clinic. The multidisciplinary team should consist of a doctor with an interest in diabetes and foot disease, podiatrists and orthotists, with access to services of vascular and orthopaedic surgeons.40 The identification of patients at risk of foot ulceration should be done on an annual basis for all patients with diabetes. Screening does not require expensive equipment and testing can be done in an ordinary clinic setting. Foot examination is frequently overlooked,41 perhaps because healthcare professionals are reassured by patients not reporting any symptoms. However, as discussed earlier, neuropathy, vascular disease and even ulceration can frequently be asymptomatic but easily diagnosed by simple clinical examination.42 Peripheral neuropathy can be recognised with standard clinical tools by finding reduced or absent vibration, pin-prick or thermal sensation in the foot. Testing with a 128-Hz tuning fork to check vibration sensation on the apex of the great toe and a 10-g monofilament to test light touch sensation at 10 sites of the foot will correctly identify 87% of patients with loss of protective sensation in the feet, who are therefore at risk of ulceration.43 Quantitative sensory testing can also be a useful adjunct. Dry and cracked skin on the feet usually signifies autonomic neuropathy; neuropathic symptoms (burning, paraesthesiae, etc.) should be sought. Peripheral vascular status is usually assessed by palpation of the peripheral pulses, and it should be remembered that absent foot pulses may be due to arterial wall calcification and not necessarily absent flow. The ABPI should be measured whenever there is any doubt, but further investigation will be dictated by individual clinical requirements.

The diabetic foot

Introduction

Epidemiology

Aetiology of foot ulceration

Peripheral vascular disease

Biomechanical aspects

Management

The ‘at-risk’ foot

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The diabetic foot

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue