Fig. 4.2

Traction used for stabilization of flail chest injury in a patient with sternum fracture. Traction tongs used to stabilize the sternum with four pounds of traction by use of overhead frame (Used with permission, Jensen 1952 [3])

In the second half of the century, the concept of “internal pneumatic stabilization” became a popular treatment strategy for stabilization of flail chest injuries [1]. In the 1970s, it was thought that internal pneumatic stabilization of the flail chest injury was a critical component of chest wall stabilization. The use of positive pressure mechanical ventilation was believed to allow for internal stabilization of the flail chest, and obligatory prolonged mechanical ventilation became a standard of care for treatment of flail chest injuries. It was not uncommon for patients to undergo tracheostomy and long-term positive pressure ventilation for 2–3 weeks until rib fractures had consolidated to some extent, regardless of the patient’s pulmonary function [4].

It wasn’t until 1975 that the work of Trinkle et al. cast doubt on this theory and practice [5]. In this retrospective matched cohort study, patients treated with obligatory mechanical ventilation (group 1) were compared to those who were treated for underlying lung injury by use of diuretics, intercostal nerve blocks, and pulmonary toilet (group 2). The results demonstrated that obligatory mechanical ventilation leads to higher rate of complications (23 % vs. 2 %, p < 0.01), longer hospital stay (22.6 vs. 9.3 days, p < 0.005), and increased mortality (21 % vs. 0 %, p < 0.01). The authors concluded that treatment of the underlying lung injury is more important than treatment of the paradoxical chest wall motion by internal pneumatic stabilization. Other authors confirmed these findings and confirmed high rates of complications in patients treated with obligatory mechanical ventilation [6]. It was recognized that mechanical ventilation should be used to correct pulmonary dysfunction and gas exchange abnormalities, rather than treat chest wall instability [5, 6].

Over the next decades, the main treatment strategy remained nonoperative, focusing on supportive mechanical ventilation in patients with respiratory dysfunction; pain management with use of epidural catheters, intercostal nerve blocks, or intravenous narcotic administration; and chest physiotherapy to clear secretions and prevent atelectasis [7–9]. Surgical fixation of the flail chest was reported; however, this was performed in rare circumstances. The methods of fixation included Kirschner wires (K-wires) [10, 11] and Judet struts [12], which are outdated modes of fixation compared to current modern technique of plates and screw fixation [8, 13] (Figs. 4.3, 4.4, 4.5, and 4.6).

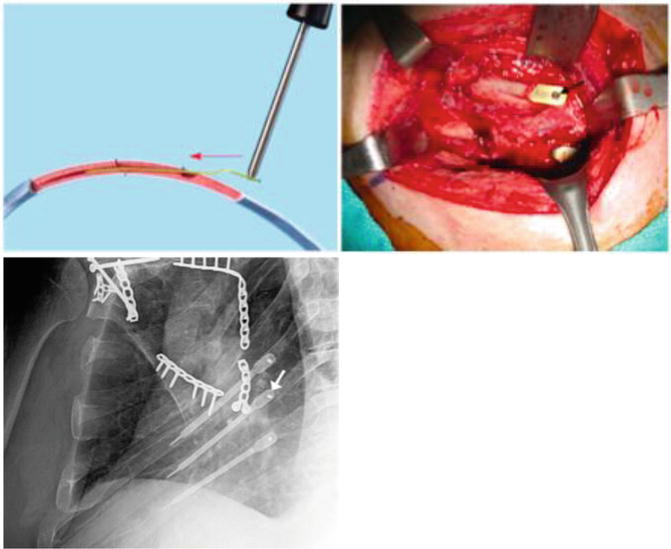

Fig. 4.5

Anatomic locations of regional anesthesia for treatment of flail chest injuries (Used with permission [14])

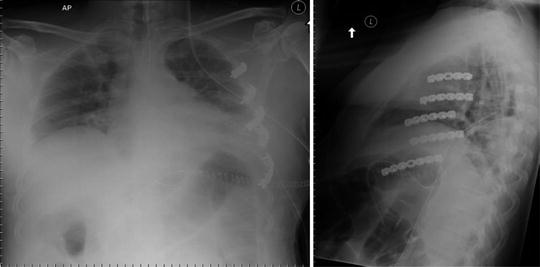

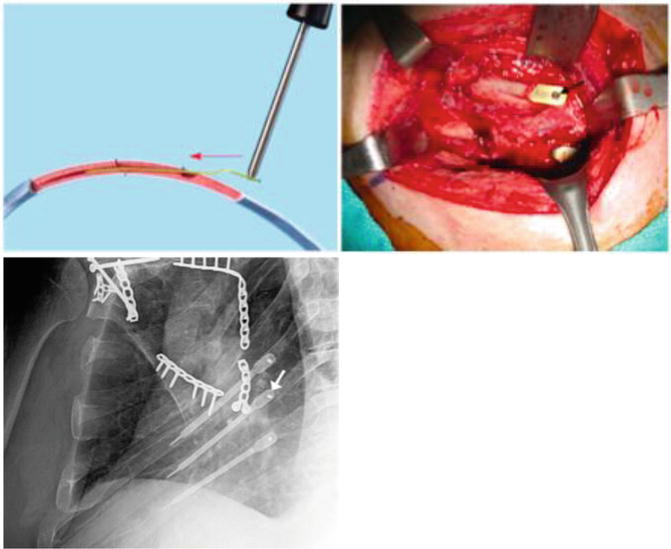

Fig. 4.6

Surgical treatment of multiple rib fractures with plate and screw fixation

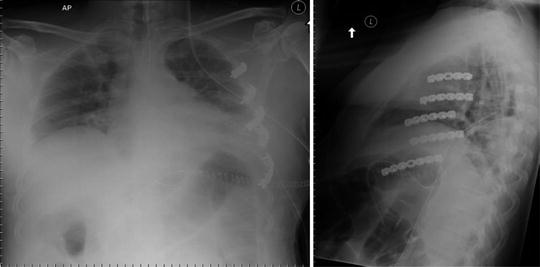

Fig. 4.7

Surgical fixation of fractured ribs with locked intramedullary implants (arrow). This patient has also undergone plate fixation of an associated scapular/glenoid fracture (Used with permission [8])

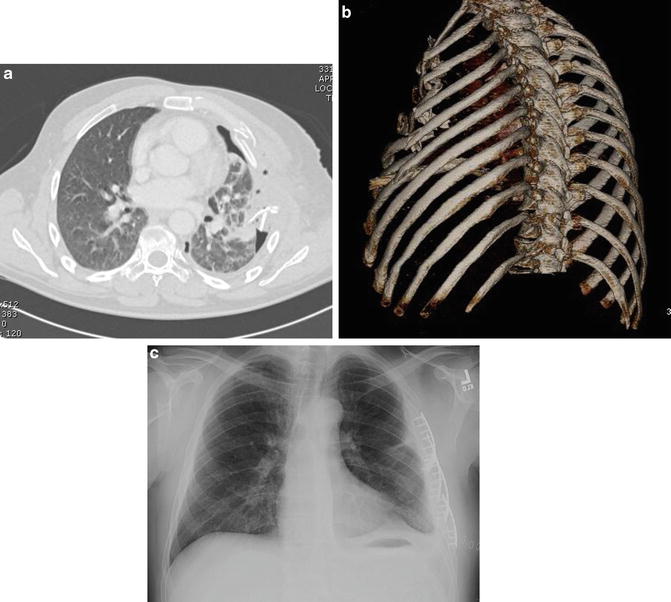

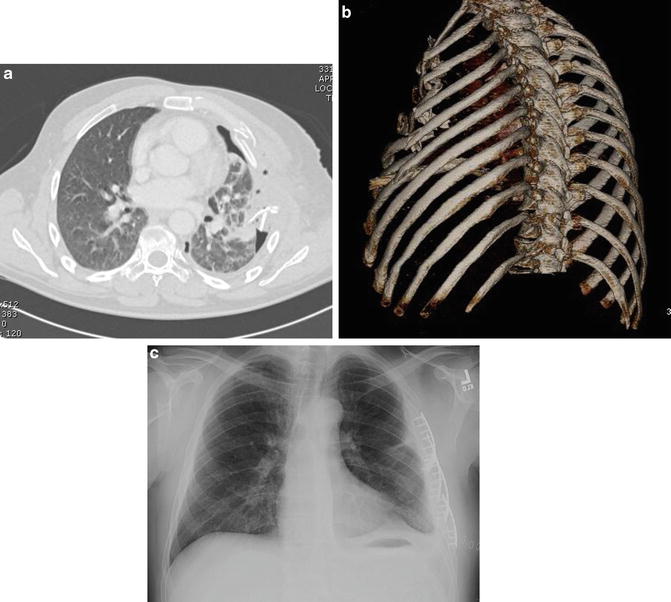

Fig. 4.8

(a) A CT scan demonstrates severe chest wall displacement with a flail segment in a polytrauma patient. There is an associated pneumothorax and significant lung parenchymal injury from displaced and penetrating ribs. (b) The 3D CT scan reconstruction demonstrates the anterolateral location of the flail segment. This type of 3D reconstruction is a valuable tool in the assessment of, and surgical planning for, these injuries. (c) Contemporary treatment through an anterolateral thoracotomy incision with plate fixation of four ribs, stabilization of the flail segment, and rapid re-expansion of the lung. Pulmonary function improved rapidly, and the patient was extubated promptly (case courtesy of W. Drew Fielder, MD, FACS)

Modern Treatment Strategies

The current modern treatment of flail chest injuries includes nonsurgical and surgical treatment strategies. A summary of these is outlined below, and further details may be found in Chaps. 5–10.

Mechanical Ventilation

Current recommendations state that obligatory mechanical ventilation solely for the purpose of overcoming chest wall instability, in the absence of respiratory failure, should be avoided [15]. Patients in respiratory distress should receive supportive mechanical ventilation and be weaned from the ventilator at the earliest time possible. Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) should be included in the ventilatory regimen [15].

Tube Thoracostomy

Patients with pneumothorax and/or hemothorax and signs of respiratory distress should undergo urgent tube thoracostomy. However, not all patients with flail chest injuries require chest tube utilization. Patients with a small pneumothorax may not require a chest tube initially; however, their condition should be monitored. If there is progression of pneumo-/hemothorax, or respiratory distress, the use of tube thoracostomy should be reconsidered. The use of positive pressure ventilation has the potential to turn a relatively small-sized or occult pneumothorax into a tension pneumothorax. Therefore, patients who require positive pressure ventilation should be monitored for development of obstructive shock and tension pneumothorax and undergo urgent tube thoracostomy if needed.

Pain Management

The optimal pain management is the key for treatment of patients with flail chest injuries. Pain management strategies include the use of regional anesthesia such as epidural catheters, intercostal nerve blocks, interpleural nerve blocks, and paravertebral blocks (Fig. 4.5) [14–16]. Other modes of pain management include use of oral and intravenous narcotic administration and patient-centered analgesia [1, 15]. The use of epidural catheters has been reported to be the most preferred method and leads to improved outcomes and lower complications when compared to other modalities [1, 15, 17]. Randomized controlled trials comparing epidural catheters to intrapleural catheters have demonstrated superiority of epidural catheters, with decreased pain, improved tidal volumes, and negative inspiratory pressures [17]. Epidural catheters have also been compared to intravenous narcotic use and have exhibited improved outcomes, such as improved subjective pain perception, pulmonary function tests, and lower rates of pneumonia, as well as decreased length of time on a mechanical ventilator or ICU stay [1, 15, 18]. They have also been shown to have lower rate of complications such as respiratory depression, somnolence, and gastrointestinal symptoms [15].

Chest Physiotherapy

Chest physiotherapy includes clearing pulmonary secretions with frequent suctioning and inspiratory spirometry, including incentive spirometry in those who have not been intubated [15, 19]. Aggressive chest physiotherapy should be practiced to minimize the likelihood of respiratory failure and decrease the risk of infection. However, percussive chest physiotherapy in a patient with multiple rib fractures must be carefully tailored to the patient’s specific area of injury to avoid inflicting unnecessary pain. In this regard, direct communication between the treating physician and the physiotherapist is mandatory.

Surgical Fixation

Surgical fixation of flail chest injures includes ORIF with use of plates and screws or intramedullary nail fixation (Figs. 4.6–4.9). In the past decade, surgical fixation has become more popular than previously, although it is still not common practice. The increase in surgical fixation has been a result of multiple published studies in the early 2000s which report improved outcomes with surgical fixation of patients with flail chest injuries [7, 10–13, 20–22]. There have been several retrospective and nonrandomized comparative studies [11, 21, 22], as well as three randomized clinical trials [10, 12, 23] that demonstrate significantly superior clinical outcomes in patients treated with surgical fixation, compared to nonoperative treatment. The reported improved outcomes with surgical fixation compared to nonoperative treatment include decreased time on mechanical ventilation [10–12], decreased length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) [10–12, 21], decreased chest infections [10–12], earlier return to work [12], decreased chronic pain [21], and decreased long-term respiratory dysfunction [24, 25].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree