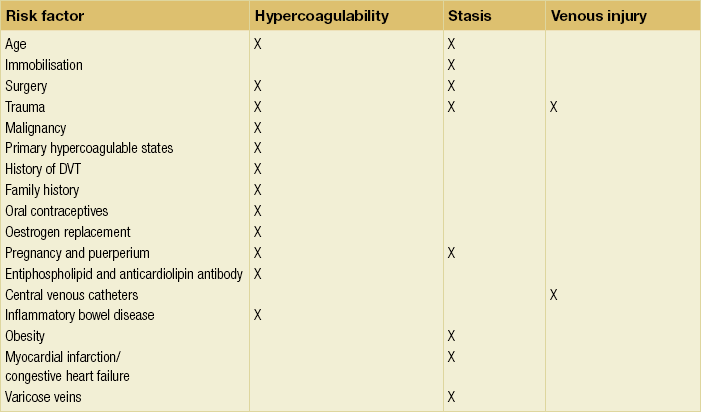

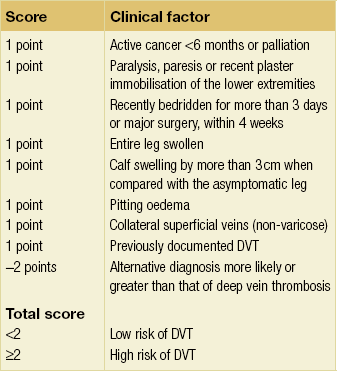

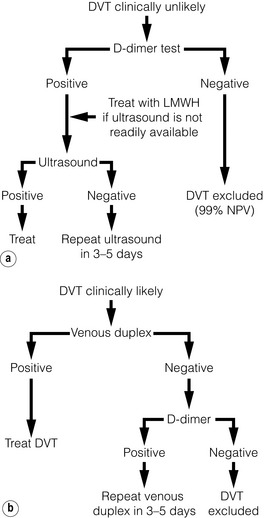

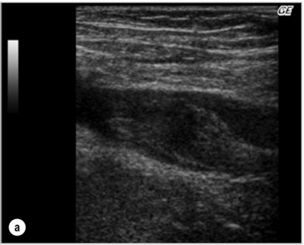

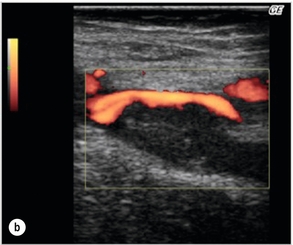

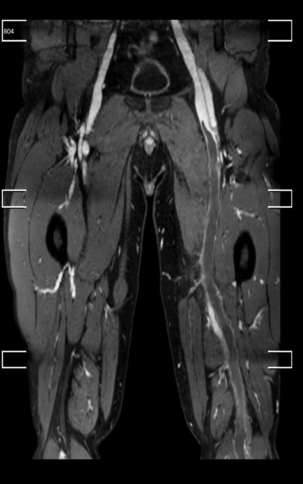

19 A good medical history from the patient will often raise suspicion regarding the underlying pathology. A previous history of operations on the leg, trauma or a history of DVT may be useful, along with an overview of the patient’s general health. There are often several differential diagnoses despite an accurate history. The correct diagnosis, or exclusion of DVT, is essential to prevent potentially life-threatening complications. Consequently, several decision tools have been developed, including the Wells score.1 It is important to ascertain the precise time point when symptoms began, as this can influence both treatment and prognosis. Patients presenting with sudden, instantaneously severe calf pain and swelling of the leg may suffer from a ruptured Baker’s cyst. A Baker’s cyst forms as a result of overproduction of synovial fluid secondary to an underlying cause such as degenerative arthritis, meniscal tears, gout or rheumatoid arthritis. It is common among adults, but can occur in children.2 A Baker’s cyst is usually located on the dorsolateral side of the knee. If the cyst bursts, immediate pain occurs, with swelling of the leg and redness, often mimicking a DVT.3 The Baker’s cyst is usually easily identified with duplex ultrasound.4 Treatment consists of anti-inflammatory medication, leg elevation and application of cold packs.5 Sudden swelling of the leg, combined with redness, pain and increased warmth, is seen in patients with erysipelas or cellulitis. Accompanying complaints can be nausea vomiting, headaches and fever. The terms erysipelas and cellulitis are both used. There is however a small distinction between the two diagnosis. They differ in that erysipelas involves the upper dermis and superficial lymphatics, whereas cellulitis involves the deeper dermis and subcutaneous fat. This manifest in a different presentation in erysipelas where there is a clear line of demarcation of the redness and the skin involved. In cellulitis there is no clear demarcation visible. Upon physical examination it is important to look for a break in the skin as a portal for entry of bacteria. Common skin barrier breaks are abrasions, insect bites, or tinea pedis. Any fluid coming from the wound should be cultured. The most likely causative bacteria are Staphylococcus aureus and Group A streptococci.6 Treatment comprises antibiotics targeted towards Gram-positive bacteria, rest and elevation. Duplex ultrasound should be considered to exclude DVT. Patients treated for erysipelas or cellulitis should experience symptom improvement with in 24 to 48 hours. Fasciitis is a very serious condition with a high morbidity and mortality. While this may present as excruciating pain,7 other clinical signs may be absent. Possible clinical signs include erythema, crepitations due to gas formed by subcutaneous bacteria, fever, nausea, vomiting, local oedema, blisters, and necrosis of the skin and underlying structures. The underlying mechanism is a bacterial colonisation of Staphylococcus aureus or Group A streptococci. The micro-organisms produce endotoxins, which cause a severe inflammatory reaction, with destruction of the deep fascia and surrounding structures. Patients with a compromised immune system are more susceptible to infection with opportunistic bacteria. If this situation is left untreated the destruction of the fascia will spread and eventually lead to the death of the patient. Treatment of necrotising fasciitis consists of aggressive surgical debridement of the infected tissues. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be given to include coverage for Gram-positive, Gram-negative and anaerobic organisms.8 Additional intensive care support is vital to improve the chance of survival. Even with optimal treatment, the mortality rate is over 30%.9 Although lymphoedema usually presents as a chronically swollen leg, it can occasionally present acutely. Lymphoedema is the result of impaired lymphatic drainage due to obstruction or destruction of lymphatic tissue. The major causes of lymphoedema can be classified as primary (hereditary) or secondary (acquired). Causes of primary lymphoedema are congenital lymphoedema, lymphoedema praecox and lymphoedema tarda. These causes manifest themselves in childhood (congenital lymphoedema), puberty (lymphoedema praecox) or early adulthood (lymphoedema tarda). Secondary lymphoedema can be caused by malignancy, surgery with lymph dissection, radiation therapy, infection of lymph nodes, recurrent cellulitis or a connective tissue disease. The management of lymphoedema is discussed in Chapter 18. Swelling of both legs is usually a sign of a systemic problem, such as heart failure, renal failure, liver failure, sepsis, pulmonary hypertension or drugs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and calcium blockers), but it is essential to rule out bilateral DVT or vena caval obstruction. History and examination will usually guide further investigation.10 If the patient has a bilateral swelling caused by a systemic disease, treatment should focus on the primary cause. If the patient uses calcium blockers or NSAIDs, alternatives for these medications can be considered. DVT is very common in the western world, with an incidence of 1.6 per 1000 persons per year.11 The incidence of DVT increases exponentially over the age of 70. In people under 18 years of age, DVT is very uncommon, with an incidence of 0.07 per 10 000 per year.12 In the 19th century, Virchow postulated the mechanisms for clot formation. The three main mechanisms are stasis of blood, vessel wall damage and hypercoagulability. Once the clot has formed it has the tendency to extend. Thrombosis in calf veins does not usually elicit much in the way of symptoms. Once the clot has propagated in the popliteal vein symptoms may become more apparent. If the clot further propagates to the femoral vein and common femoral vein, obstructing venous outflow from the leg, more severe symptoms are likely. At the most severe end of the spectrum is phlegmasia cerulea alba or phlegmasia cerulea dolens (see Fig. 19.1). These conditions require immediate attention from the physician, because of possible limb ischaemia and loss of the leg. DVT should be viewed as a dynamic condition, and often results from a combination of risk factors that shift the balance of coagulation to a hypercoagulable state. A number of risk factors have been identified, which can be categorised relating to Virchow’s triad (Table 19.1).13 Thrombus usually forms around valves on the endothelium. In 80% of cases one or more risk factors can be determined in the patient. Because clinical signs are not very specific for DVT, clinical decision tools have been developed to aid patient management. The Wells score is the most widely used and validated clinical decision tool.14,15 The patient’s risk for having a DVT is assessed by the criteria shown in Table 19.2. The patient is then categorised into either a high- or low-risk group. A Wells score of 2 or more indicates that the patient has a high risk of DVT.1 A Wells score of 0 or 1 puts the patient in the low-risk group. The Wells score combined with a D-dimer test can guide the clinician with regard to the need for a duplex scan. A patient with either a Wells score of 2 or more and/or positive D-dimer test will need a duplex scan to look for a possible DVT. Conversely, a Wells score of 0 or 1 with a negative D-dimer almost entirely rules out DVT and the patient does not require a duplex scan. Studies show the negative predictive value for this combination of findings to be 99% for excluding DVT.16 The clinical decision flow chart is shown in Fig. 19.2. The current standard for diagnosing a DVT is a two-point duplex scan.17 The non-invasive two-point ultrasound examination looks at the popliteal vein and the common femoral vein. The physician will compress the vein at these two points. If the vein is non-compressible, the presence of thrombus is proven. Thrombus may also be visible on sonography and venous flow may be absent. Alternative diagnoses, such as a Baker’s cyst, may also be identified on ultrasound. If the duplex scan is inconclusive, but the suspicion of DVT is still high, a conventional venogram or other imaging may be considered. Conventional venography is still the gold standard, but duplex ultrasound is much more accessible, less invasive and easier to perform. In cases of recurrent DVT it may prove difficult to differentiate between newly formed thrombus and old residual thrombus. Standardised documentation of the previous thrombus location may be helpful. The size of the vein and the identification of scarring may help guide the clinician, with small scarred veins most likely to represent chronic changes. In experienced hands it is also possible to estimate thrombus age based on homogeneity. A thrombus with a homogenous aspect is more likely to be fresh. It should also be recognised that fresh thrombus may form within a recanalised area of old thrombus. Figure 19.3 shows a duplex scan of the common femoral vein with intraluminal thrombus. New techniques are becoming more readily available for imaging of the venous system, including computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography. These techniques can be used to identify DVT but are especially useful in determining the precise extent of the thrombus and any underlying stenosis. In particular, the iliac vein segment and the inferior vena cava can be assessed in a simpler manner than with duplex ultrasound.18,19 These techniques will become very important in identifying patients suitable for more aggressive intervention than standard anticoagulation therapy. New reporting standards have been developed to standardise the scoring of venous disease with different imaging techniques (LOVE score). With these standardised reports it is possible to identify and report DVT systematically and stratify patients into different treatment groups (LET score).20,21 This will become more important as treatment options advance further. Figure 19.4 shows a magnetic resonance venograph with a DVT present in the popliteal vein and femoral vein of the left leg. Figure 19.4 Magnetic resonance venography with a DVT present in the popliteal vein and femoral vein of the left leg.

The acutely swollen leg

Medical history

Differential diagnosis

Baker’s cyst

Cellulitis and erysipelas

Necrotising fasciitis

Lymphoedema

Bilateral swelling

Deep venous thrombosis

Pathophysiology of DVT

Clinical decision rules

Imaging techniques

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The acutely swollen leg

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue