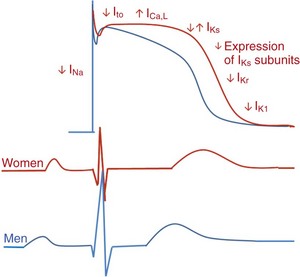

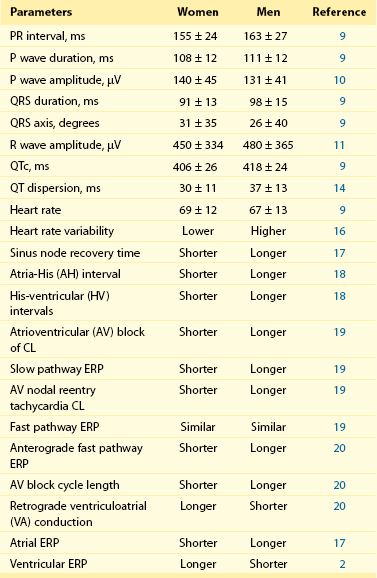

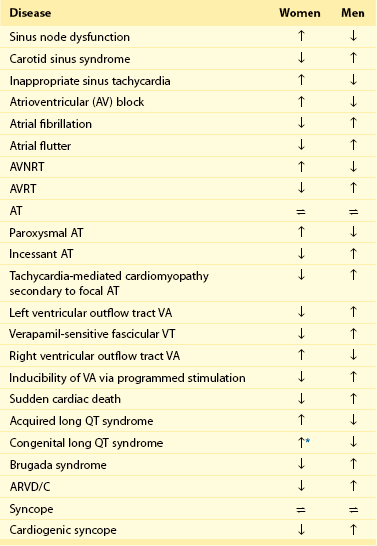

107 Relatively small changes in ionic currents may increase susceptibility to arrhythmias by altering AP morphology and causing repolarization abnormalities or QT prolongation. Several sex-based differences in function, structure, quantity, and currents of cardiomyocyte ion channels, including sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), and calcium (Ca2+) and their components, have been defined (Figure 107-1). Figure 107-1 Sex Differences in Basic Electrical Properties of the Heart, Including Ion Channel Function and Action Potential Morphology Sex hormones affect Na+ channel function and transmural distribution of INa.1 In the canine left ventricle, INa amplitude is smaller in female epicardial and endocardial layers. Testosterone is able to decrease transmural dispersion in amplitude of INa in females, resulting in similar amplitudes as in males. Transmural dispersion of INa increases the risk of ventricular arrhythmias in females. In castrated male dog hearts, INa amplitudes are similar to those in female hearts. A recent study on healthy human transplant donor hearts showed reduced expression of a variety of IK subunits, including HERG, minK, Kir2.3, Kv1.4, KChIP2, SUR2, and Kir6.2, in women compared with men.2 An isoform switch in Na+/K+-ATPase was also found in women. In female mouse hearts, total IK, transient outward K+ current (Ito) and slow delayed-rectifier K+ current (IKs) densities are lower in a higher estrogen state, reflecting a direct effect of estrogen on K+ currents.3 This lower current density is associated with downregulation of Kv4.3 and Kv1.5 transcript levels. In female canine ventricles, total densities of Ito, IKs, and L-type Ca2+ currents are different and lead to transmural variation in cardiac repolarization.4 Transmural differences in IK in females cause differences in ventricular repolarization and provide a molecular link for increased susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias in women. However, sex differences in ventricular repolarization are species dependent. In male and female guinea pig hearts, expression levels of different K+ channels, such as ERG, KvLQT1, mink, and Kir2.1, and the density of K+ currents (IKr, IKs, and IK1) are similar.5 Gender effects on ICa function and cardiomyocyte Ca2+ content have also been documented. Larger L-type Ca2+ (ICaL) currents are present in all layers of female canine ventricles compared with males.4 The ICaL channel plays a significant role in sex-based differences in myocardial excitation-contraction coupling. The required Ca2+ for maximum contractile force is lower in males than in females. However, these findings are species specific, as no sex difference in myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity is seen in the cat ventricle. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ concentration also has an effect on sex-specific cellular Ca2+ regulation. Sex differences in cellular Ca2+ transients have been measured in individual epicardial myocytes from female and male rat left ventricles.6 Ca2+ reuptake was smaller in magnitude and longer in duration, with greater local variability in females. The rate sensitivity of Ca2+ alternans was higher in females without significant heterogeneity in cellular responses. An increase in the Ni-sensitive Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and reduced β-adrenergic responsiveness have been noted in male swine left ventricular cardiomyocytes compared with females in tachycardia. The morphology of the cardiac AP plays an important role in the genesis of arrhythmias. Depolarizing inward and repolarizing outward ionic currents, intracellular ion concentrations, transmembrane potentials, and expression of ion channels determine AP morphology and the electrophysiological properties of cardiomyocytes. Thus, AP characteristics, including AP duration, repolarization alternans, restitution slope, and adaptation to heart rate, are expected to be different in women than in men (see Figure 107-1) in terms of cellular ionic processes, as outlined earlier. Regional factors such as transmural dispersion could also alter AP morphology in women. AP duration is longer in female than male ventricles in various species, including humans, adult mice, guinea pigs, dogs, and rabbits (see Figure 107-1).4,7,8 Human ventricular cardiomyocytes in women have a longer AP duration, larger transmural heterogeneity of AP duration, and greater susceptibility to proarrhythmic early afterdepolarizations than those in men. However, male cells have more prominent phase 1 repolarization and greater susceptibility to all-or-none repolarization. These differences are associated with altered ICaL, Ito, and IKr densities. Female sex hormones cause prolongation of AP duration.3 Slower restitution properties and repolarization alternans are noted in female rat cardiomyocytes at slower heart rates.6 Underlying ionic mechanisms of rate-dependent changes in AP morphology include variation in Ito1 and IKs in AP restitution, as well as ICaL and INaK in AP accommodation.7 The sex-based difference in AP restitution is thought to be related to heterogeneity in the density and recovery kinetics of Ito1. Transmural dispersion of cardiac repolarization based on sex is associated with Ito, IKs, and ICaL ionic currents, as is shown in adult canine left ventricular myocytes. Female M cells have longer AP durations with increasing transmural AP heterogeneity.4 The ionic bases of these sex-specific differences are reported to be associated with variations in Ito and sustained outward K current (Isus) and IKur, IK1, IK, IKr, and ICaL currents in different studies. Sex-based differences in baseline electrocardiographic intervals and heart rate were first recognized by Bazett almost a century ago and are summarized in Table 107-1. Since that time, multiple studies have confirmed his findings and have provided mechanistic insights into the causes of sex differences. Table 107-1 Sex Differences in Basic Electrocardiographic and Electrophysiological Parameters CL, Cycle length; ERP, effective refractory period; µV, microvolt; ms, millisecond. Substantial sex differences in conduction intervals, as well as in P wave and QRS morphology, have been noted (see Figure 107-1 and Table 107-1). Women have shorter PR intervals, QRS and P wave durations, and RR intervals compared with men, but QTc intervals are longer in women.8,9 P wave amplitude is greater in women than in men of all ages.10 Sex differences in these parameters are recognized at an early age and persist with the aging process. Differences in PR interval and P wave duration progressively increase with aging, whereas P wave amplitude progressively decreases in both sexes with aging.10 The QRS complex is shorter in duration and lower in amplitude in women after adjustment for left ventricular mass and body weight.11 R wave amplitude is also lower in women. Thus, the diagnostic accuracy of QRS morphology–based electrocardiographic criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy is significantly less in women than in men. Since Bazett’s initial report, it has been known that women have longer QTc intervals than men (see Figure 107-1 and Table 107-1). This QT prolongation is associated with greater risk of ventricular arrhythmias such as polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) or torsades de pointes (TdP). The sex difference in QT prolongation is associated with sex hormones.8,9,12 During childhood, QTc intervals are similar in boys and girls, but they shorten in boys when puberty starts. In adults, men with higher testosterone levels continue to have shorter QTc intervals than women. Athletes who take large doses of anabolic steroids have shorter QTc intervals too. In parallel, women with virilization syndromes have shorter QTc intervals compared with castrated men and healthy women. After the age of 65 years, QTc gradually increases in men and becomes comparable with that in women. However, hormone replacement therapy does not have an effect on the QTc interval of postmenopausal women. Thus, testosterone modulates QTc more effectively than estrogen. Significant seasonal variation in QTc intervals has been found among adult men but not in women. Monthly mean QTc intervals were consistently greater in women than in men by 5.2 ± 2.3 ms, with no seasonal changes noted.13 Another important sex difference in the electrocardiogram is QT dispersion. Increased QT dispersion has a significant role in the genesis of reentrant arrhythmias and SCD. One study showed that QT dispersion is greater in men than in women and demonstrates prominent circadian variation.14 Nevertheless, QT variability is a predictor of arrhythmic events after myocardial infarction in women who have a depressed left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).15 Data derived from the Women’s Health Initiative Study show that nonspecific repolarization changes are more frequent in women and predict cardiovascular events. Repolarization inhomogeneity, as reflected in variation in mean RR intervals and beat-to-beat QT intervals in an established time domain, is higher in women. Sex differences in heart rate and variability in heart rate under different physiological or pathophysiological conditions have been studied extensively. The mean heart rate at rest is higher in women than in men by 2 to 6 bpm.8,9 This difference is persistent even with sympathetic and parasympathetic blockade; therefore it is thought to be associated with dissimilarity in intrinsic sinus node properties. Sex differences in heart rate and heart rate variability fluxuate with age, race, physical conditioning, and comorbidities. Heart rate variability is a known sensitive index of cardiac autonomic regulation. One study showed that heart rate variability is greater in men than in women in the age range of 33 to 47 years.16 Heart rate variability is also lower in women with newly diagnosed hypertension and in younger women with depressive symptoms after an acute coronary event. Cardiac autonomic modulation is significantly different in men and women during change of posture. Men have higher values of frequency-domain parameters of heart rate variability (low-frequency power and total power) in supine and standing positions. However, high-frequency power is similar in both sexes. Intracardiac electrophysiological measurements have been performed in men and women to characterize sex-based differences in electrical properties of the heart. The fundamental differences between women and men in sinus node function, AV conduction, and atrial and ventricular myocardial electrical properties are well documented (see Table 107-1). Sinus node function is different in females starting from childhood.17 Sinus node recovery time is significantly shorter in women than in age-matched men with structurally normal hearts.17,18 Corrected sinus node recovery time remains shorter in young and adult females compared with males. AV conduction properties are also different in women, as reflected by shorter PR, atrial-His (AH), and His-ventricular (HV) intervals, as well as shorter AV block cycle lengths.18 Overall, men acquire AV block more often than women. The incidence of dual AV nodal pathways is similar in both sexes. However, women with symptomatic AV nodal reentry tachycardia (AVNRT) have shorter slow pathway effective refractory periods (ERPs) and tachycardia cycle lengths but similar fast pathway ERPs compared with men.19 A recent study confirmed these findings, with the exception of fast pathway physiology. The anterograde fast pathway ERP was found to be shorter in women than in men.20 During ventricular pacing in the absence of pharmacologic stimulation, women more often have retrograde ventriculoatrial (VA) conduction; men are more likely to exhibit VA dissociation. A sex-specific approach to the diagnosis and treatment of patients is essential in providing optimal care. The clinical presentation and prognosis of cardiovascular diseases, including heart rhythm disorders, are different in women. This section reviews sex differences in specific arrhythmias, including supraventricular tacharrhythmias (SVTs), ventricular arrhythmias, SCD, inherited arrhythmias, and syncope (Table 107-2). Table 107-2 Sex Differences in the Incidence and Prevalence of Heart Rhythm Disorders *Women have a higher incidence of events after age 15 years. Sinus node–related disorders are known to be different in both sexes such that women are more frequently affected by sick sinus syndrome, and carotid sinus syndrome occurs more commonly in men (see Table 107-2). Inappropriate sinus tachycardia is diagnosed much more commonly in women younger than 40 years. Abnormal autonomic regulation of the sinus node or a related immunologic disorder involving cardiac β-adrenergic receptors has been speculated to be the cause of this condition in women. The incidence and prevalence of SVT in men and women vary according to the type of SVT. Patients with symptomatic paroxysmal SVT have been evaluated in the electrophysiology laboratory for determination of sex-based differences. In one study, the incidence of various arrhythmias in women was found to be 63% AVNRT, 20% AV reentrant tachycardia (AVRT), and 17.0% atrial tachycardia; in men it was 45% AVNRT, 39% AVRT, and 17% atrial tachycardia.21 A clear hormonal effect on triggering SVT episodes has been noted in women. The frequency of symptomatic SVT episodes is more pronounced during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle in premenopausal women. SVT is more inducible in a perimenstrual phase during an electrophysiological study. SVT episodes often cluster during this period; therefore it is important to consider timing when scheduling electrophysiological studies and ablation procedures in women, to maximize the chances for successful induction and ablation of arrhythmia.

Sex Differences in Arrhythmias

Basic Electrophysiology

Cellular Electrophysiology

Ion Channels

Action potential duration is longer in women (red) than in men (blue). Women have slower restitution properties, and men have more prominent phase 1 repolarization. These differences are regulated by altered ionic currents in different phases of the action potential. In parallel, significant sex-based differences in electrocardiographic intervals are seen. Women (red) have shorter PR intervals and QRS and P wave durations compared with men (blue). However, QTc intervals are longer in women. Although P wave amplitude is greater in women, R wave amplitude is less.

Action Potentials

Electrocardiography

Baseline Intervals

Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability

Electrophysiological Study

Sinus Node Function

Atrioventricular Conduction Intervals

Presentation and Management of Specific Arrhythmias

Sinus Node Dysfunction/Tachycardia

Supraventricular Tachyarrhythmias

Sex Differences in Arrhythmias