In contrast to ST-elevation myocardial infarction treatment, there is no clear definition for when and which patient to discharge. Our study’s main goal was to test the hypothesis that an early discharge strategy (within 48 to 56 hours) in patients with successful primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is as safe as in patients who stay longer. The Early Discharge after Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention trial was designed in a prospective, randomized, multicenter fashion and registered with http://clinicaltrials.gov ( NCT01860079 ). Of 900 patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction, the study randomized 769 eligible patients to the early or the standard discharge group. The study’s primary outcomes were all-cause mortality and readmission at 30 days. We considered assessment of functional status and health-related quality of life to be secondary outcomes. The early discharge group had significantly shorter length of hospital stay compared with the standard discharge group (45.99 ± 9.12 vs 114.87 ± 63.53 hours; p <0.0001). Neither all-cause mortality nor readmissions were different between the 2 study groups (p = 0.684 and p = 0.061, respectively). Quality-of-life measures were not statistically different between the 2 study groups. Our study reveals that discharge within 48 to 56 hours after successful PPCI is feasible, safe, and does not increase the 30-day readmission rate. Moreover, the patients perceived health status at 30 days did not differ with early discharge.

In contrast to the clear understanding of how we treat ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), there is no clear definition for when to discharge and which patient to discharge. Data on early discharge strategies have been quite limited. There are 4 randomized trials investigating the possibility of early discharge after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI). However, certain limitations of these studies are preventing implementation of an early discharge strategy for all-comers, particularly because of the underrepresentation of older patients in clinical trials. The verification of this policy is also needed for patients with multivessel disease. The first prospective randomized trial, The Primary Angioplasty in MI II (PAMI II), is partly obsolete, as major changes have been made in PPCI with respect to devices and adjunctive medications. The other 3 randomized trials were single-center pilot studies with a small number of patients. Therefore, the previously mentioned literature information warrants testing the reproducibility of safety end points in a large-scale multicenter trial before application of the early discharge strategy in clinical practice.

Methods

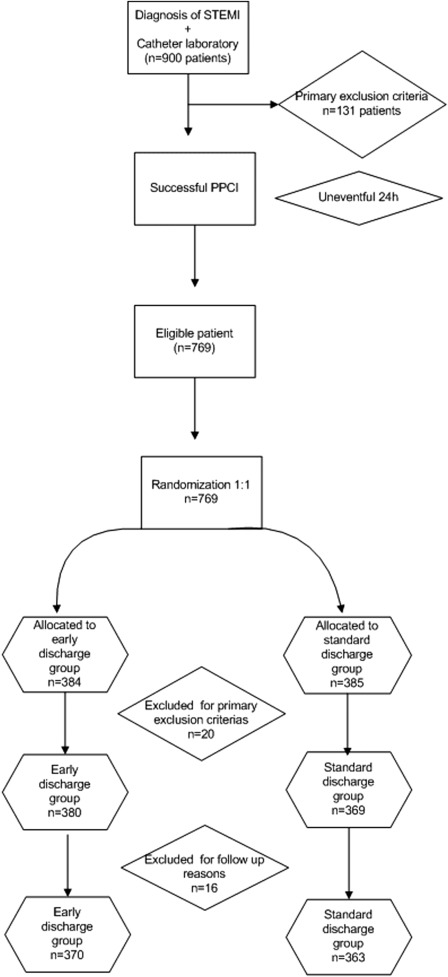

We designed the Early Discharge after Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention trial in a prospective, randomized, multicenter fashion to determine if early hospital discharge is feasible and safe in the real world for all patients who were treated successfully with PPCI. We enrolled 900 subjects in the trial. After applying the exclusion criteria, we divided the remaining patients—363 patients in the standard discharge arm and 370 in the early discharge arm ( Figure 1 ). Our study population included patients with STEMI presenting to the 3 study center hospitals. All study centers are teaching hospitals with emergency PCI and coronary artery bypass surgery programs. Physicians and catheterization laboratory staff are available on a 24-hour basis. The study’s inclusion criteria were as follows: acute STEMI, defined as >30 minutes of continuous typical chest pain and ST-segment elevation ≥2 mm in 2 contiguous electrocardiography leads and/or left bundle branch block within 12 hours of symptom onset, a successful PPCI procedure, and an uneventful 24-hour follow-up period, single epicardial artery to be treated. Potentially eligible patients were approached at their acute admission and the exclusion criteria were as follows—unsuccessful primary percutaneous intervention, patients treated with thrombolytic agents for the index STEMI, cardiogenic shock, stroke within a month, signs of heart failure (Killip II to IV), hypotension (<100 mm Hg systolic blood pressure) persisting after PPCI, chest pain recurrence, and clinically significant arrhythmia (requiring treatment) occurring more than 6 hours after PPCI.

We performed the study in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was approved by the ethics committee of Acibadem University (Sayı:B.30.2.ACU.0.00.00.050-06/780, ATADEK 2013-472). All local PCI centers involved in the study also approved it. In accordance with recommendations, we have registered the EDAP-PCI trial with http://clinicaltrials.gov ( NCT01860079 ). All participants provided written informed consent.

All patients received chewable 300 mg aspirin and clopidogrel (600 mg loading dose) before coronary angiography. Emergency coronary angiography and PCI were performed by percutaneous femoral approach. Heparin (10,000 IU) was administered when arterial access was secured. Angiographic assessments were made at the treating hospital by visual assessment. Infarct-related artery was graded according to Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction classification. All patients were admitted to the coronary care unit. Intravenous heparin (500 IU/hour or subcutaneous low–molecular weight heparin 1 mg/kg/day × 2 [according to creatinine level]) was given to patients with atrial fibrillation or a recent history of any embolus and deep venous thrombosis. All patients received 100 mg aspirin and 75 mg clopidogrel on daily basis. The use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was left to the discretion of the operator. Concomitant medical treatment with β blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and statins were prescribed according to 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association guidelines for the management of STEMI.

We randomized 769 eligible patients to 1 of 2 groups, using a block design to ensure that the same number of patients would be assigned to each discharge group. We implemented randomization after an uneventful 24-hour follow-up of the patient. In the early discharge group, patients were targeted for hospital discharge within 48 to 56 hours. After early discharge, these patients received additional follow-up at days 1, 7, and 20 by telephone; an appointed nurse was in charge of questioning any complaints and medicine usage compliance. Any suspicious symptom was discussed with the attending physician, and if needed, the patient was transferred to the concerned PCI center. The nurse’s role was to educate patients about the nature and management of their disease, with a focus on medications and facilitation of discharge planning by ensuring patients were aware of all follow-up appointments. In the control group, discharge planning and follow-up were left to the treating physician and nursing team. At 1 month, all patients (early discharge plus control) were seen in the cardiology outpatient clinic. After routine 1-month examination, the first 150 patients from each discharge group were sent to a blinded research assistant to assess functional status and health-related quality of life by filling in the 36-item Medical Outcomes Study health status questionnaire (SF-36).

The primary end points were all-cause mortality by 1 month and readmission due to reinfarction, unstable angina, arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, revascularization, stroke, or major bleeding. Assessment of functional status and health-related quality of life were secondary outcomes.

Successful PPCI was defined as Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 2 to 3 flow and <20% residual stenosis after PPCI; congestive heart failure as Killip’s class II to IV ; reinfarction as an increase in creatine kinase (CK) more than twice the last value associated with CK-MB ≥10% of the total CK- and ST-segment reelevations; unstable angina as a clinical symptom associated with electrocardiogram changes, hypotension, new murmur, or CK-MB elevation; stroke as an acute neurological event lasting more than 24 hours; major bleeding as red cell transfusion at the discretion of the treating physician or which led to a decrease in hemoglobin level of more than 3 g/dl; and coronary vessel disease as a presence of a >50% lesion in major epicardial coronary arteries or a left main coronary artery lesion. To have a clear understanding of the risk status, we assessed the Zwolle PPCI Index after the randomization. All findings, including clinical and laboratory data, were documented in the subjects’ medical records.

We analyzed all categorical data with the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate and continuous values with a normal distribution were compared between the groups using the Student t test or Wilcoxon test when data were not normally distributed. Comparisons were analyzed by the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test between the early discharge and standard treatment arms for primary and secondary outcomes. We used the statistical Student t test and the Mann-Whitney U test to compare scales of the SF-36, according to whether normality assumptions were met. To assess distribution of each variable, we used the Levene’s and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. All p values will be 2-sided, and a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical studies were carried out with SPSS program, version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois).

Results

During the 2-year study period, 900 patients with PPCI arrived at the 3 different study centers. After the exclusion of 131 patients due to primary exclusion criteria, such as unsuccessful PPCI (n = 34%), cardiogenic shock (n = 15%), signs of heart failure (n = 27%), stroke within a month (n = 2%), patients treated with thrombolytic agents for the index STEMI (n = 7%), chest pain recurrence (n = 13%), clinically significant arrhythmia (requiring treatment) occurring more than 6 hours after PPCI (n = 14%), hypotension (<100 mm Hg systolic blood pressure) persisting after PPCI (n = 7%), and inability to get informed consent (n = 12%), 769 patients were randomized into 2 groups ( Figure 1 ). Twenty patients were excluded because of primary exclusion criteria, such as signs of heart failure (n = 7%), clinically significant arrhythmia requiring treatment (n = 3%), chest pain recurrence (n = 4%), cardiogenic shock (n = 1%), or social repatriation reasons (only in early discharge group, n = 5%). Furthermore, 16 patients were excluded for follow-up reasons, such as losing contact with the patient or the patient refusing to show up at the cardiology outpatient clinic at the end of 1 month. The study was terminated with 370 patients in the early discharge group and 363 patients in the standard discharge group ( Figure 1 ).

The 2 groups were well balanced with regard to demographics and clinical data ( Table 1 ). Neither all-cause mortality nor readmissions were different between the 2 study groups ( Table 2 ). Quality of life measures were not statistically different between the 2 study groups ( Figure 2 ).

| Standard Discharge (n=363) | Early Discharge (n=370) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54.63±11.82 | 54.55±10.25 | 0.925 |

| Men | 316 (87.1 %) | 324 (87.6)( %) | 0.834 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 73 (20.1 %) | 72 (19.5)( %) | 0.825 |

| Hypertension | 112 (30.9 %) | 115 (31.1 %) | 0.947 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 41 (11.3 %) | 37 (10.0 %) | 0.570 |

| Family history of coronary heart disease | 178 (49.0 %) | 182 (49.2 %) | 0.967 |

| Smoker | 289 (79.6 %) | 295 (79.7 %) | 0.969 |

| Stable angina pectoris | 45 (12.4 %) | 18 (4.9 %) | <0.001 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 13 (3.6 %) | 17 (4.6 %) | 0.489 |

| Previous percutaneous coronary intervention | 14 (3.9 %) | 8 (2.2 %) | 0.179 |

| Previous coronary artery by-pass greft | 4 (1.1 %) | 3 (0.8 % ) | 0.723 ∗ |

| congestive heart failure | 44 (12.1 %) | 62 (16.8 %) | 0.074 |

| cerebrovascular accident | 3 (0.8 %) | 1 (0.3 %) | 0.369 ∗ |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 76.69 ±15.33 | 75.81 ± 13.91 | 0.417 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 124.65 ±23.98 | 124.95 ± 21.53 | 0.858 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 75.74 ±15.49 | 78.16 ±15.02 | 0.034 |

| Creatinin (mg/dl) | 0.89 ±0.46 | 0.87 ±0.64 | 0.695 |

| Glucose(mg/dl) | 118.57 ±49.57 | 115.83 ±59.02 | 0.524 |

| Mean Zwolle score | 1.86 ±2.27 | 1.93 ±2.48 | 0.873 |

| Anterior Myocardial infarction | 209 (57.6%) | 213 (57.6 %) | 0.998 |

| Number of narrowed arterial vessel 1-2-3 | 180-125-58 (45.6%-34.4%-15.1 %) | 194-120-56 (51.0%-33.4%-15.6%) | 0.743 |

| Narrowed artery (mean) | 1.66±0.70 | 1.62±0.73 | 0.498 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 45.51±10.43 | 44.86±11.21 | 0.741 |

| Door to balon time (minutes) | 52.42±144.00 | 44.11±69.89 | 0.341 |

| Pain to balon time (minutes) | 230.89±313.22 | 193.27±249.91 | 0.087 |

| Discharge time (hours) | 114.87±63.53 | 45.99±9.12 | <0.0001 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree