Rheumatic Heart Disease

Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease were major causes of death and disability throughout the world 50 years ago. Today, rheumatic fever is so rare in the United States and other westernized countries that whole generations of medical students are graduating without ever seeing a case. On the other hand, throughout the Third World—in Africa, Asia, and Latin America—rheumatic heart disease is common and virulent. In countries of the Eastern Mediterranean, Arab children sometimes progress to severe congestive heart failure from rheumatic heart disease by the age of 12. Even in the United States, the disease persists in remote areas and in isolated ethnic groups. Why have rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease disappeared from such a large part of the world? The answer is simple: Rheumatic heart disease is completely preventable. It’s the only kind of heart disease that is.

Rheumatic Fever: The Cause and Consequences

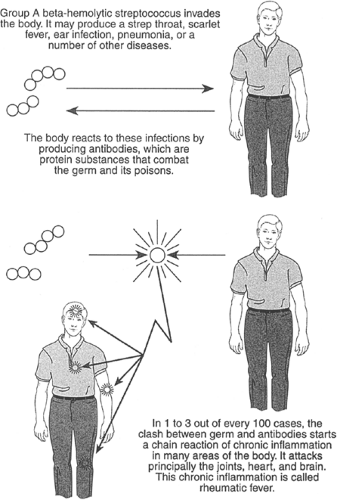

Rheumatic fever is caused by the reaction of the body to a specific kind of germ—the group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus, or strep, as almost everyone knows it. It is caused by a specific kind of infection with this germ—the familiar “strep throat.”

To understand what happens you have to know something about the way the body reacts to infections. The only reason you don’t die when the first bacteria attack you is that the cells of your body have ways of resisting the bacteria by actually destroying them, and by neutralizing the toxic products they produce. This is called the immune reaction of the body. (In the H. G. Wells science fiction story that scared half the United States, a gang of Martians almost conquered the world until they were killed by bacteria; their bodies had no immune systems to fight off infection.)

Sometimes the immune system overreacts. The body goes on producing antidotes to the poisons of the bacteria long after the bacteria are gone. These antibodies, as they are called, actually become harmful to the tissues of the body and cause what is called autoimmune disease.

Imagine a company of soldiers defending a fort against invaders who keep coming over the walls. The soldiers kill all the invaders but become so trigger-happy that they keep blasting away, shooting holes in the fort itself and destroying the very structure they’re supposed to be defending. This is what happens in autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosis, rheumatic fever, and many others (Fig. 14-1).

The sequence of events in rheumatic fever goes like this. Day 1: A streptococcus attacks the throat, producing some signs or symptoms of infection. Days 4-5: With or without treatment, the sore throat gets better. Days 7-14: If the infection isn’t treated with antibiotics, the rheumatic reaction will follow in one case out of a hundred or a thousand, depending on whether there’s an epidemic going on and where the patient lives. Widespread inflammation starts in many parts of the body brought on by the immune reaction to the streptococcus. This reaction may attack the joints, the skin, the heart, the lungs and, later, the brain. After a few days, the inflammation in these tissues takes on a specific form called the Aschoff body. Each Aschoff body under the microscope looks like an adolescent pimple that never quite comes to a head but remains angry and red. There are millions of these microscopic sores and they keep recurring in new crops. This continuing inflammation can go on for many months.

In the joints, it produces redness, swelling, and tenderness. In the skin, it produces a short-lived rash, called erythema marginatum, that’s gone in a day or two. In the lungs, the inflammation can produce pneumonitis, or inflammation of lung tissue. In the brain, as a late complication, it can produce chorea, or St. Vitus’ dance. None of these reactions are serious. They all go away with no serious aftereffects.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree