Resection of Superior Sulcus Tumors

Christine Lau

G. Alexander Patterson

The term “superior sulcus” is really a misnomer in that there is no specific anatomic structure that corresponds but the term has come to refer to those primary lung tumors that occur in the apex of the lung that involve the chest wall and often other structures that reside in the thoracic outlet. These lesions can present with pain in the nerve distribution of the eighth cervical and first and second thoracic nerve roots. In addition, Horner syndrome may be present as a result of involvement of the stellate ganglion of the sympathetic chain. Such patients have the classic presentation described by Pancoast-Tobias syndrome. Patients with C8-T1 nerve root involvement may also present with typical neurologic findings of the “ulnar hand.” However, the majority of patients with apical lung tumors present with nondescript but persistent shoulder or upper chest pain. Many of these patients are seen by orthopedic surgeons or chiropractors and are treated as if the problem is strictly a tendonitis or other orthopedic problem, and the only imaging studies obtained are shoulder films that when viewed in retrospect clearly show the lesion. It is not uncommon for patients to be treated for many months prior to a correct diagnosis being made. Posteroanterior and lateral chest radiograph may demonstrate nothing more than apical pleural thickening. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) usually depict the lesion clearly.

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

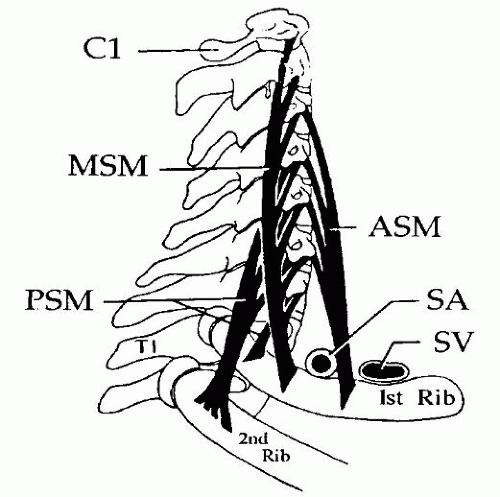

The insertion of the anterior, middle, and posterior scalenus muscles on the first and second ribs, respectively, divides the thoracic inlet into three compartments (Fig. 32.1). The anterior compartment contains the platysma and sternocleidomastoid muscles, the external and anterior jugular veins, the inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle, the subclavian and internal jugular veins and their major branches, and the scalene fat pad. The middle compartment includes the anterior scalene muscle with the phrenic nerve lying on its anterior aspect, the subclavian artery with its primary branches except the posterior scapular artery, the trunks of the brachial plexus, and the middle scalene muscle. Finally, the posterior compartment, which lies posterior to the middle scalene muscle, includes the long thoracic and external branch of the spinal accessory nerves, the posterior scapular artery, the sympathetic chain and stellate ganglion, vertebral bodies, intervertebral foramina, and intercostal nerves.

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The anatomic location and the pattern of invasion of the apical lung lesion determine the presenting symptoms and signs. Anterior apical tumors generally present with chest wall or shoulder pain. Hand or arm swelling suggests subclavian vein invasion on the left or brachiocephalic invasion on the right. The phrenic nerve may be involved as it crosses the scalenus anticus muscle. These anterior lesions usually do not involve the brachial plexus.

Tumors invading the middle compartment of the thoracic inlet may present with signs and symptoms related to compression or infiltration of the middle and lower trunks of the brachial plexus, which manifest clinically as pain radiating to the shoulder and upper extremity. Often these tumors spread along the fibers of the middle scalene muscle.

Tumors located posteriorly are usually located in the costovertebral groove and commonly present with some or all the signs and symptoms of the Pancoast-Tobias syndrome, because of the involvement of the C8 and T1 nerve roots, the posterior aspect of the subclavian and vertebral arteries, the sympathetic chain, the stellate ganglion, and prevertebral muscles. These tumors have a propensity to spread along the nerve roots up to the spinal canal through the intervertebral foramina. In addition, vertebral bodies may be involved by direct extension.

DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATIONS

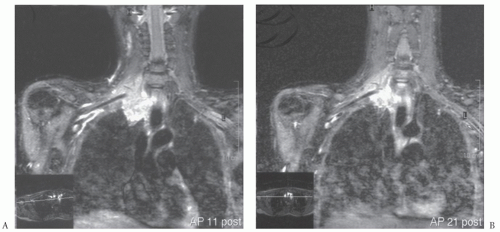

Unfortunately, the diagnosis of superior sulcus tumor is often made late because symptoms are not specific, neurologic findings are sometimes absent, and routine imaging of the chest and shoulder are often not revealing. Often symptoms are mistakenly attributed to arthritis or other inflammatory conditions of the shoulder or cervical spine. The radiologic findings can be subtle because these lesions are often hidden behind the first rib and clavicle. Posteroanterior and lateral chest X-ray have little role in evaluation of the superior sulcus tumor. Superb imaging of the lesion and its local extension can be obtained using modern computerized tomographic techniques. High-resolution images with three-dimensional volume averaging allow precise location of extent of the tumor, nerve involvement, and spinal invasion. Specific nerve root or vascular invasion is better assessed by MRI. The easiest way to obtain a tissue diagnosis is by fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Transbronchial biopsy may be considered, but these lesions are so peripheral that this option is rarely useful. If there is a suspicion of extensive pleural invasion or pleural metastases, video-assisted thoracic exploration may be utilized for diagnostic purposes. All patients should undergo a thorough search for hematogenous metastases. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging should be a routine part of the evaluation to assess both regional lymph node involvement and distant metastatic disease. Because these are T3 lesions, we employ mediastinoscopy and supraclavicular lymph node biopsy in every patient. Patients with N2 or N3 nodal involvement are not candidates for resection. The initial investigation of the potentially operable patient also includes preoperative cardiopulmonary functional tests and other investigations required for any major pulmonary resection.

INDICATIONS

INDICATIONSDetermination of specific root involvement is important. T1 invasion may be evident only from pain and paresthesia in the medial aspect of the upper arm. C8 invasion will be associated with loss of strength in intrinsic muscles, lack of thumb opposition, and numbness in the fifth finger and medial half of the ring finger. These observations can be confirmed by electromyography, but clinical examination is usually sufficient. Phrenic nerve invasion is detected by elevation and immobility of the ipsilateral diaphragm. Vascular invasion is usually apparent by good-quality contrast CT scans, but additional information can be obtained by MRI. If vascular invasion is suspected, arteriography may be helpful, and Doppler ultrasound will demonstrate associated cerebrovascular arthrosclerotic changes, which might affect the decision regarding operability. Radiologic determination of vascular and nerve root invasion is sometimes equivocal. Apposition of the tumor to major structures does not confirm invasion or preclude surgical exploration to determine resectability (Fig. 32.2). Spinal invasion or extradural extension is often evident on CT scans, but occasionally MRI is necessary to rule out subtle spinal involvement.

These investigations are not merely academic. Extent of disease and, therefore, likelihood of complete resection must be determined preoperatively. Loss of the T1 nerve root is inconsequential, but resection of T1 and C8 will leave a severely impaired “ulnar hand,” which the patient may not accept. Subclavian vein or arterial invasion is not a specific contraindication to resection. The vein can be resected without reconstruction. Arterial resection will require primary reconstruction or interposition grafting. Vascular invasion describes a T4 lesion and predicts a decreased long-term survival. Limited involvement of the vertebra such as a transverse process or partial vertebral body involvement is not a contraindication to resection. In fact, these resections can be conducted with local resection of the affected bone to obtain tumor-free margins. Patients with more extensive single or double vertebral involvement may be candidates for complete resection. Recent advances in techniques of vertebral resection and spinal stabilization make such resection feasible. Limited experience with such resections has been reported from a small number of experienced centers, and early results are encouraging.

Absolute contraindications to resection include N2 or N3 disease, extensive vascular invasion, brachial plexus involvement more extensive than C8 and T1, and multiplelevel vertebral involvement with extension into the spinal canal.

After the 1924 and 1932 reports of Henry K. Pancoast describing the tumors of the thoracic apex, the entity was considered incurable until the report of Chardack and MacCallum in 1956 and the description of Shaw and Paulson in 1961. Radiation therapy given preoperatively over a 10- to 20-day period at a dose of 30 to 45 Gy had been the standard approach since the Shaw

and Paulson report. In recent years, demonstration of tumor response following induction chemoradiation gave rise to an interest in its application in patients with superior sulcus tumors. A multicenter cooperative group trial demonstrated that cisplatin and etoposide and 45 Gy of radiation improved the rate of complete resection, pathologic complete response, local recurrence, and intermediate-term survival compared with historical controls treated only with induction radiotherapy. For this reason and because of the success of combinedmodality therapy in stage IIIA lung cancer, induction chemoradiation has become the standard of care for superior sulcus tumors in most centers. It has also been pointed out by some authors that induction therapy should include higher doses of radiation as it has been shown that this does not increase perioperative morbidity but may result in a higher rate of complete response and ultimately long-term survival.

and Paulson report. In recent years, demonstration of tumor response following induction chemoradiation gave rise to an interest in its application in patients with superior sulcus tumors. A multicenter cooperative group trial demonstrated that cisplatin and etoposide and 45 Gy of radiation improved the rate of complete resection, pathologic complete response, local recurrence, and intermediate-term survival compared with historical controls treated only with induction radiotherapy. For this reason and because of the success of combinedmodality therapy in stage IIIA lung cancer, induction chemoradiation has become the standard of care for superior sulcus tumors in most centers. It has also been pointed out by some authors that induction therapy should include higher doses of radiation as it has been shown that this does not increase perioperative morbidity but may result in a higher rate of complete response and ultimately long-term survival.

PERIOPERATIVE PATIENT MANAGEMENT

Preoperative preparation is as for any major pulmonary resection. A double-lumen endotracheal tube or bronchial blocking catheter for left-sided lesions is helpful. Standard monitoring lines include an arterial line in the contralateral radial artery. Two venous lines should be placed to allow for rapid volume replacement as needed.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

SURGICAL TECHNIQUEDifferent operative approaches are necessary depending upon the location of the primary tumor. The surgeon must be familiar with these various approaches. The goal of the operation is en bloc resection of the upper lobe along with involved ribs and other structures, including transverse processes, the lower roots of the brachial plexus, the stellate ganglion, and the upper dorsal sympathetic chain.

There are three approaches most commonly employed for these lesions. The posterior approach described by Shaw and Paulson is ideal for lesions situated posteriorly. The anterior cervicothoracic approach described by Dartevelle is ideal for the management of anterior lesions. The hemiclamshell approach is less commonly employed but is useful for anterior or posterior lesions.

We believe that whatever approach is selected, an initial cervical exploration is warranted. This is particularly true when a posterolateral Shaw-Paulson resection is anticipated. With the patient supine, shoulders elevated, neck extended, and head turned to the contralateral side, a transverse incision is made immediately above the clavicle. The platysma muscle is divided, as is the clavicular head of the sternomastoid muscle. The supraclavicular fat pad is excised and submitted for frozen-section examination to rule out the involvement of supraclavicular lymph nodes. The phrenic nerve is elevated away from the scalenus anticus muscle, so that the muscle may be divided. This exposes the subclavian artery and the lower roots of the brachial plexus. Anterior displacement of the brachial plexus exposes the scalenus medius muscle, which is then divided, taking care to preserve the long thoracic nerve. By mobilizing and inspecting these structures through a small cervical incision, tumor extent can be assessed and a judgment made regarding the possibility of subsequent complete resection before exposing the patient to the morbidity of a major posterior thoracotomy and rib resection. In addition, this anterior superior mobilization facilitates subsequent dissection and resection through the posterolateral thoracotomy.

Posterolateral Approach (Shaw-Paulson)

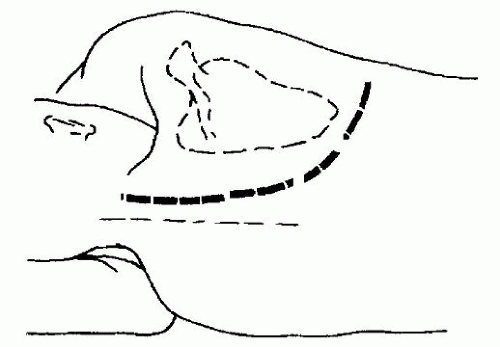

The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position, leaning slightly forward. The upper arm is loosely supported by folded sheets and is free to move as the scapula is elevated. The skin preparation is carried out from the base of the skull (included are the spinal processes above C7) and down to the iliac crest and to the midline posteriorly and anteriorly.

Incision

A limited posterolateral incision is made, dividing the latissimus muscle, and entry is made into the chest through the fourth or fifth interspace. The pleural space and hilum are examined to exclude the presence of metastatic disease. This initial exploration also permits assessment regarding anterior (several centimeters away from the lesion) and inferior (one rib and one interspace) margins of resection.

Subsequently, the incision is extended superiorly between the spinous processes and the medial border of the scapula to the level of the seventh cervical vertebra (Fig. 32.3). The trapezius muscle is divided along the full length of the incision. The rhomboid muscles from superior to inferior are then divided in the line of the incision. The rhomboid muscles insert into the medial border of the scapula. Care should be taken to avoid injury to the dorsal scapular nerve and the satellite scapular artery, which run down the medial border of the scapula. The division of the rhomboid muscles elevates the medial border of the scapula from the chest wall.

A large Finochietto retractor is then placed with its lower blade in the interspace incision and the upper blade on the tip of the scapula. Opening the retractor elevates the scapula off the chest wall and exposes the subscapular musculature. These muscles are then divided with cautery up to the level of the first rib.

Chest Wall Resection

The chest wall resection is completed first, allowing the lung to be completely mobilized and permitting a safer subsequent pulmonary resection. All involved chest wall should be resected en bloc. Extrapleural dissection without rib excision, mentioned only to be condemned, results in incomplete resection and almost certain local recurrence. The lowermost rib to be preserved is identified, and an interspace incision is made along its superior border, extending from the anterior margin of resection to the transverse process posteriorly. The division of the ribs is started anteriorly. Intercostal muscles are divided with electrocautery.

Using rib shears, the ribs are divided anteriorly in succession from inferior to superior (Fig. 32.4). Traction on the previously divided anterior margins of the involved ribs exposes the anterior aspect of the first rib. For posterior tumors, the anterior aspect of the first rib can easily be encircled and divided with angled rib shears. The anterior and middle scalene muscles, previously divided from above, are exposed. The posterior scalene muscle is

divided where it crosses the lateral border of the first rib. The superior margin of the first rib is then exposed by careful superior mobilization of the subclavian vein, artery, and inferior aspect of the brachial plexus. At this point, the operation is continued posteriorly.

divided where it crosses the lateral border of the first rib. The superior margin of the first rib is then exposed by careful superior mobilization of the subclavian vein, artery, and inferior aspect of the brachial plexus. At this point, the operation is continued posteriorly.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree