Repair of Paraesophageal Hernia

Arjun Pennathur

Matthew J. Schuchert

James D. Luketich

INTRODUCTION

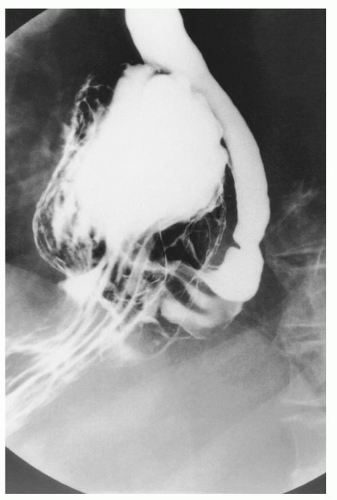

Paraesophageal hernias represent subtypes of hiatal hernia. The most common form of hiatal hernia is the simple or sliding (type I) hiatal hernia (95%), in which the gastroesophageal (GE) junction migrates above the diaphragmatic hiatus, frequently associated with incompetence of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). The remaining forms of hiatal hernia can be classified as paraesophageal (5%). Type II paraesophageal hernias are rare but are characterized by the position of the GE junction below the diaphragm, with a portion of the fundus and greater curvature of the stomach migrating through a hiatal defect alongside the esophagus. In type III paraesophageal hernias, the GE junction and fundus are displaced superiorly, with protusion through a hiatal defect (Fig. 35.1). Type IV hernias are defined as herniation of the entire stomach, omentum, and/or other intra-abdominal organs such as the transverse colon, and spleen into the mediastinum. The characteristic anatomic defects of paraesophageal hernias include enlargement of the diaphragmatic hiatus and abnormal laxity of the gastrosplenic and gastrocolic ligaments, allowing migration of the stomach (and other abdominal contents) into the chest. Giant paraesophageal hernias (GPEHs) are defined by the presence of greater than one-third of the stomach within the chest.

The actual incidence of paraesophageal hernia is unknown. It is estimated that paraesophageal hernias make up 3% to 15% of all hiatal hernias, producing an estimated incidence of 15 to 45 per 100,000 individuals within the general population. Symptoms of paraesophageal hernia frequently include obstructive symptoms, such as dysphagia, and reflux symptoms (heartburn, regurgitation, etc.). Chest pain (especially postprandial) is a common finding and is frequently mistaken for anginal symptoms. Postprandial distress, nausea, bloating, and anemia are also commonly encountered. A relatively asymptomatic but insidious symptom is occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Anemia is reported in 20% to 30% of patients with paraesophageal hernias in published series, but the rate of blood loss is slow and is rarely associated with hemodynamic compromise. A significant fraction of patients with paraesophageal hernia are asymptomatic or complain of only minor symptoms. The exact proportion of such patients is difficult to estimate for obvious reasons. Interestingly, it has been estimated that up to 89% of patients denying symptoms will actually describe some symptoms when questioned carefully.

Symptoms can be progressive, however, and can potentially result in catastrophic complications. Mortality from strangulation may be >50%, depending on the patient’s age and the potential for delay in diagnosis. This has led many to argue that symptomatology is not a reliable predictor of who might progress to acute complications, and that elective surgery should be performed on most patients with a GPEH, in particular, those with organoaxial rotation as seen on a barium esophagram. Prompt elective repair after diagnosis has been recommended to avoid the development of such complications. When the repair is performed electively, excellent control of symptoms (>90%), with a low perioperative mortality of <1% to 2%, can be achieved.

Despite the foregoing observations, the beliefs held by surgeons are still largely based on small patient series and anecdotal case reports. There is little doubt that patients presenting with obstructive symptoms, bleeding, or both should undergo elective hernia repair. However, surgical correction of truly asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic paraesophageal hernias is controversial. Some studies suggest that asymptomatic patients have an 85% annual probability of remaining asymptomatic. This implies that about one in six patients will develop new symptoms, which can then be treated with elective repair. The probability that a patient’s initial presentation would require an emergency operation has been estimated to be only 1% per year. Although mortality of an emergency operation has been reported as high as 50%, a pooled analysis of the largest series demonstrated an aggregate operative mortality rate of 17%. In a larger analysis of a nationwide database, the mortality rate for emergency operation for paraesophageal hernia (n = 1035) in 1997 was only 5.4%. Thus, for a 65-year-old asymptomatic patient, who has an 18% lifetime risk of developing life-threatening symptoms (1% per year) requiring emergency surgery (5.4% mortality), the overall lifetime risk of death with observation is approximately 1%, comparable to the expected 1% to 2% mortality of elective repair. Decision analysis models have failed to demonstrate a gain in quality-adjusted life expectancy with elective laparoscopic repair of asymptomatic paraesophageal hernias when compared with watchful waiting.

When symptoms arise, the only effective treatment of paraesophageal hernias is surgical repair. The surgical technique involves reduction of the herniated contents back into the abdomen, excision of the hernia sac, and closure of the hiatal defect. These procedures can be performed transthoracically or transabdominally with laparotomy or laparoscopically. In extremely high-risk patients with minimal symptoms, an anterior gastropexy can be performed to help prevent the development of incarceration or organoaxial volvulus. In the absence of reflux symptoms, the need to perform an antireflux procedure has been debated. However, up to 60% of patients with type III hernias have also been shown to have hypotensive LES pressures and abnormal 24-hour pH-monitoring studies. In addition, with the repair of large paraesophageal hernias, there is significant dissection performed around the hiatus, the phrenoesophageal ligament is divided, and the lower esophageal antireflux mechanism is affected; thus, many surgeons (including us) recommend routinely performing an antireflux procedure during elective repair. The use of partial (Belsey, Dor, and Toupet) or complete (Nissen) wraps has been reported, each with good results. The choice of wrap is determined by the individual patient’s underlying anatomy,

symptom complex, and esophageal motility in addition to the surgeon’s preferences.

symptom complex, and esophageal motility in addition to the surgeon’s preferences.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

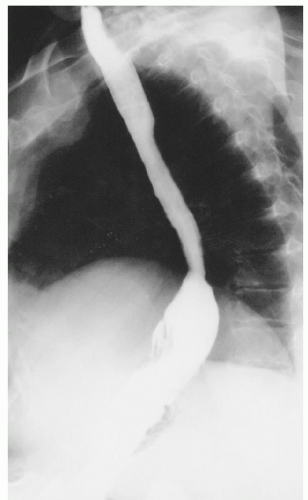

Preoperative assessment includes a barium esophagram in order to definitively establish the diagnosis (Fig. 35.1). The barium esophagram is a critical component of evaluation and demonstrates the paraesophageal hernia; it can also give an estimation of esophageal length in addition to providing information on the presence of strictures or other sequelae of GE reflux. Upper endoscopy is also critical and allows assessment of the gastric anatomy, location of the GE junction, assessment for short esophagus (Fig. 35.2), esophagitis and other complications of reflux disease, and potentially excludes other abnormalities such as Barrett’s esophagus, or neoplasia. It is also important to consider performing esophageal function studies. Esophageal manometry can be particularly useful for the evaluation of esophageal motor function, the presence of peristalsis, evaluation of the amplitude of contractions, and may influence the choice of fundoplication; in addition, it may allow the assessment of esophageal length (Maziak et al.,). However, it should be noted that manometry and 24-hour pH studies may not be feasible because the degree of anatomic distortion frequently interferes with the reliable performance of these studies. When performed, it should be done with caution in view of the anatomic distortion, and in a few centers the catheter is placed with endoscopic guidance. Patients also undergo a complete cardiopulmonary evaluation for clearance and risk assessment prior to repair of the paraesophageal hernia. Active pulmonary infection is treated prior to surgery, and patients are advised to stop smoking.

SURGICAL APPROACHES

Traditionally, the repair of a GPEH has been performed through an open laparotomy or thoracotomy. Increasingly, the repair of GPEH is being performed using minimally invasive techniques with a laparoscopic approach. In this chapter, we discuss the laparoscopic approach and the transthoracic approach for repair of GPEH.

Laparoscopic Repair of Giant Paraesophageal Hernia

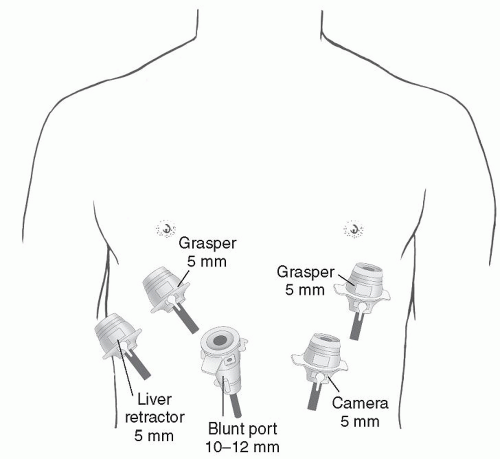

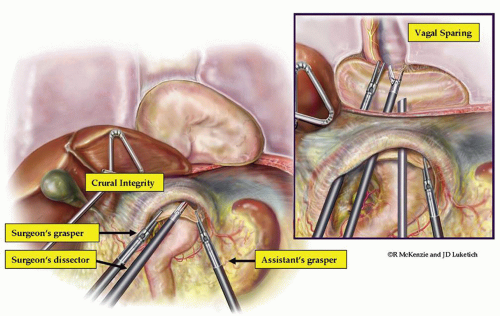

In the operating room, after intubation, we start with the esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) performed by the surgeon for confirmation of previous endoscopic findings. It is important not to insufflate too much air at the beginning of the procedure, since this will interfere with the laparoscopy. Standard laparoscopic port placement is used as shown in Figure 35.3. To facilitate the ease of mediastinal dissection, the abdominal port incisions can be shifted slightly cephalad in the case of a GPEH. The left lateral segment of the liver is retracted anteriorly with a 5 mm flexible retractor (Snowden Pencer, Genzyme, Tucker, GA) and secured to a stationary holding device (Mediflex, Islanda, NY). Dissection is begun by identifying the sac, dissecting the sac, and subsequently inverting the mediastinal hernia sac and pulling it back into the abdomen along with the herniated stomach (Fig. 35.4). Avoidance of direct traction on the stomach by using a “hand over hand” technique results in less trauma to the stomach

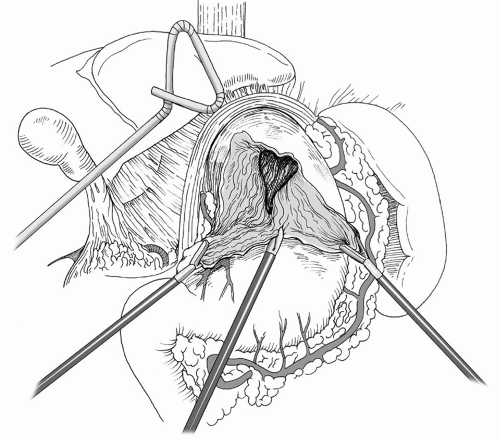

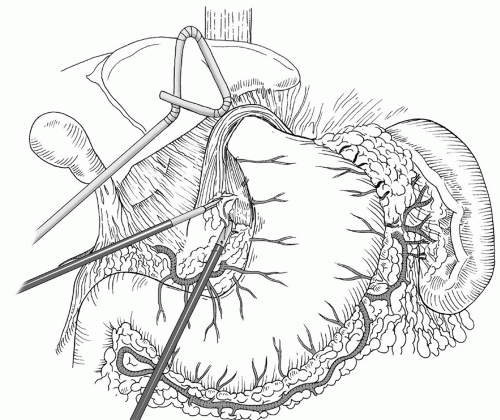

while reducing the herniated intrathoracic stomach. The crural reflection of the sac is incised, and the flimsy mediastinal attachments to the sac are carefully taken down by the harmonic scalpel (Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH) or the ultrasonic shears (U.S. Surgical Corp, Norwalk, CT). (Fig. 35.5). Care is taken to identify and preserve the proximal anterior and posterior vagus nerves during this portion of the dissection. Similarly, the adjacent pleura must be identified and swept laterally away from the plane of dissection. The surgeon and the anesthesiologist must communicate closely during this portion of the procedure because a sudden drop in blood pressure or significant increase in inspiratory pressures may indicate the development of a tension pneumothorax, which can be readily treated by placement of a pigtail catheter or a chest tube. Once the sac is completely freed up it, along with the contents, is reduced back into the abdomen and the redundant sac may be carefully excised avoiding injury to the vagi (Figs. 35.5 and 35.6). The complete dissection and reduction of the hernia sac with its contents from the chest to the abdomen is a critical component of successful surgery for GPEHs. With the delivery of the sac into the abdomen, the herniated stomach (and other herniated intra-abdominal structures) is reduced back into the peritoneal cavity. This portion of the case is also critical in achieving maximal esophageal mobilization and a tension-free repair. Inferior traction on the gastric fundus and epiphrenic fat pad is then performed to allow complete dissection of the right and left crus. A retrogastric/retroesophageal window is then created to expose the posterior portion of the left crus. At this point, the division of the short gastric vessels is performed in order to fully mobilize the fundus of the stomach.

while reducing the herniated intrathoracic stomach. The crural reflection of the sac is incised, and the flimsy mediastinal attachments to the sac are carefully taken down by the harmonic scalpel (Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH) or the ultrasonic shears (U.S. Surgical Corp, Norwalk, CT). (Fig. 35.5). Care is taken to identify and preserve the proximal anterior and posterior vagus nerves during this portion of the dissection. Similarly, the adjacent pleura must be identified and swept laterally away from the plane of dissection. The surgeon and the anesthesiologist must communicate closely during this portion of the procedure because a sudden drop in blood pressure or significant increase in inspiratory pressures may indicate the development of a tension pneumothorax, which can be readily treated by placement of a pigtail catheter or a chest tube. Once the sac is completely freed up it, along with the contents, is reduced back into the abdomen and the redundant sac may be carefully excised avoiding injury to the vagi (Figs. 35.5 and 35.6). The complete dissection and reduction of the hernia sac with its contents from the chest to the abdomen is a critical component of successful surgery for GPEHs. With the delivery of the sac into the abdomen, the herniated stomach (and other herniated intra-abdominal structures) is reduced back into the peritoneal cavity. This portion of the case is also critical in achieving maximal esophageal mobilization and a tension-free repair. Inferior traction on the gastric fundus and epiphrenic fat pad is then performed to allow complete dissection of the right and left crus. A retrogastric/retroesophageal window is then created to expose the posterior portion of the left crus. At this point, the division of the short gastric vessels is performed in order to fully mobilize the fundus of the stomach.

Assessment of Short Esophagus

In the setting of a GPEH, careful identification of the GE junction after fat pad excision frequently reveals a shortened esophagus. The esophageal fat pad is carefully and completely mobilized medially, sweeping the anterior vagus to the right of the esophagus (Fig. 35.7). The distal esophagus is then mobilized at the level of the diaphragmatic hiatus circumferentially, and the surgeon then determines whether esophageal shortening is present. The proper assessment of esophageal length can be tricky because there is a tendency to overestimate the intra-abdominal length of the esophagus because of the diaphragmatic elevation caused by the pneumoperitoneum as well as the downward traction that is applied to the stomach. If the GE junction does not remain below the diaphragmatic hiatus with an adequate segment of tension-free intra-abdominal esophagus (ideally 2 to 3 cm), then further mediastinal mobilization of the esophagus should be performed, extending higher into the mediastinum to the inferior pulmonary vein, and in extreme cases, the dissection can be carried significantly higher if needed to gain additional esophageal length. The esophageal length should again be reassessed, with the goal of an adequate, tension-free intra-abdominal esophageal segment of 2 to 3 cm. If after extensive mediastinal mobilization, there is inadequate esophageal length, we then perform a Collis gastroplasty prior to fundoplication. This can be done with an end-to-end anastomosis (EEA) stapler (Figs. 35.8, 35.9, 35.10) or a GIA stapler. At present, we prefer to perform the Collis gastroplasty with a wedge gastroplasty technique, using a GIA stapler (Figs. 35.11 and 35.12).

Fig. 35.5. Complete reduction of the herniated stomach back in the abdomen, with complete reduction of the hernia sac. |

As mentioned earlier, we routinely perform a fundoplication to prevent reflux since it is highly likely that the preceding dissection has disrupted the function of

the LES. The choice of the type of fundoplication depends on the results of physiologic testing. In general, we prefer a floppy Nissen fundoplication (Fig. 35.13). This is performed after the surgeon places an esophageal bougie (54F), with direct laparoscopic vision of the distal esophagus, the GE junction, and the stomach. A floppy Nissen fundoplication is performed, and the bougie is removed. In brief, after complete mobilization of the distal esophagus and stomach, and determination of the location of the GE junction after dissection of the GE fat pad, an atraumatic instrument is passed in the retroesophageal window. The fully mobilized fundus is grasped and brought through the retroesophageal window with proper orientation. When the fundus is fully mobilized, there should be no or minimal tension and no tendency for the fundus to retract back through the retroesophageal window. A “shoe shine maneuver” is then performed to evaluate the tightness of the wrap, its mobility, and length. Subsequently, a floppy Nissen fundoplication is performed with space behind the wrap and the esophagus to allow the passage of an atraumatic instrument. Both the Collis gastroplasty and the fundoplication may be omitted in some high-risk patients, and instead a gastropexy is performed to anchor the stomach to the abdominal wall. While some have performed this as a single point or with the placement of a gastrostomy tube, we perform the gastropexy with several interrupted heavy mattress sutures anchoring the stomach to the diaphragm and the anterior abdominal wall. We start these sutures anchoring the stomach to the left crura and then to the anterior abdominal wall.

the LES. The choice of the type of fundoplication depends on the results of physiologic testing. In general, we prefer a floppy Nissen fundoplication (Fig. 35.13). This is performed after the surgeon places an esophageal bougie (54F), with direct laparoscopic vision of the distal esophagus, the GE junction, and the stomach. A floppy Nissen fundoplication is performed, and the bougie is removed. In brief, after complete mobilization of the distal esophagus and stomach, and determination of the location of the GE junction after dissection of the GE fat pad, an atraumatic instrument is passed in the retroesophageal window. The fully mobilized fundus is grasped and brought through the retroesophageal window with proper orientation. When the fundus is fully mobilized, there should be no or minimal tension and no tendency for the fundus to retract back through the retroesophageal window. A “shoe shine maneuver” is then performed to evaluate the tightness of the wrap, its mobility, and length. Subsequently, a floppy Nissen fundoplication is performed with space behind the wrap and the esophagus to allow the passage of an atraumatic instrument. Both the Collis gastroplasty and the fundoplication may be omitted in some high-risk patients, and instead a gastropexy is performed to anchor the stomach to the abdominal wall. While some have performed this as a single point or with the placement of a gastrostomy tube, we perform the gastropexy with several interrupted heavy mattress sutures anchoring the stomach to the diaphragm and the anterior abdominal wall. We start these sutures anchoring the stomach to the left crura and then to the anterior abdominal wall.

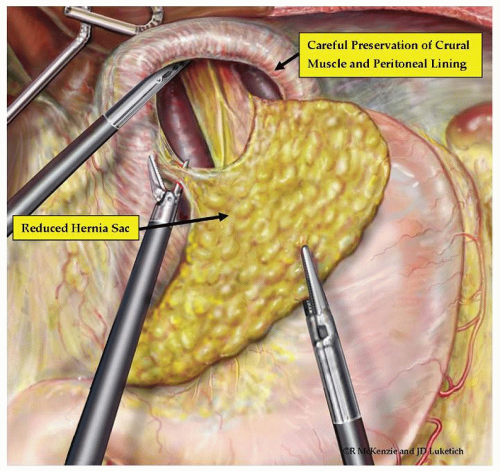

Approximation of the Crura

During the dissection, it is critical to maintain the peritoneal lining in an effort to preserve the integrity of the crura, and fully mobilize the crura. The crura are fully mobilized by dividing the phrenogastric, phrenosplenic, and retrogastric attachments. This mobilization, along with complete mobilization of the hernia and sac, allows the crura to be approximated primarily without excess tension in most cases. In some patients where crural tension is still present, inducing a small, left-sided pneumothorax may yield a “floppy diaphragm sign”, which allows a much easier tension-free primary repair. This should be done in close coordination with anesthesia, and subsequently, the surgeon can place a small pigtail catheter and eliminate the pneumothorax. This catheter can then be removed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree