Pulmonary Metastases: The Role of Surgical Resection

Pulmonary metastasectomy refers to the resection of secondary pulmonary malignancy. Most patients who develop pulmonary metastases are not curable, owing to presentation with extrathoracic metastases and lack of effective systemic therapy. Although there are no prospective, randomized trials comparing pulmonary metastasectomy to medical therapy or observation, metastasectomy has gained wide acceptance for patients who present only with metastases to the lungs. Several retrospective studies demonstrate an apparent survival advantage in patients with secondary pulmonary malignancy who undergo complete resection, comparing survival after resection to historical data for unresected patients, for whom survival is poor.

An important study that assessed the long-term results of pulmonary metastasectomy was based on an analysis of the International Registry of Lung Metastases.1 This collaborative project retrospectively reviewed 5206 cases of lung metastasectomy performed in several institutions. Patients with a single metastasis had a survival of 43% at 5 years, compared with 34% in those with two or three metastases, and 27% in those with four or more metastases. The most important determinant of survival, however, was resectability: the ability to achieve complete resection of all recognizable pulmonary metastases. The overall 5-year survival for patients who underwent complete resection was 36%, with a median survival of 35 months. In those patients who had undergone incomplete resection, the 5-year survival was only 13%, and the median survival was 15 months.1 These findings suggest that surgical resection offers a survival advantage for some patients.

A prognostic model was also created to select those who would benefit most, including the parameters of resectability, disease-free interval (DFI), and the number of metastases. Four distinct prognostic groups were identified: group 1 is the resectable group with no risk factors (DFI > 36 months and single metastasis); group 2 is the resectable group, with one risk factor (DFI < 36 months or multiple metastases); group 3 is the resectable group, with two risk factors (DFI < 36 months and multiple metastases); and group 4 is the unresectable group. Median survival was 61 months for group 1, 34 months for group 2, 24 months for group 3, and 14 months for group 4.1 This prognostic model was presented as a reasonable guide to select patients for surgery.

In general, to be considered for pulmonary metastasectomy patients must fit the following criteria: the primary disease is controlled (or controllable); there is no other distant disease; complete resection of pulmonary involvement is achievable with adequate pulmonary reserve; and there are no effective medical therapies. For pulmonary metastasectomy to have survival value, the primary tumor itself must be controlled or controllable. If the pulmonary metastases are recognized metachronously, the site of the primary tumor is examined to exclude local recurrence. If the pulmonary disease has presented synchronously, the primary tumor is assessed and a decision is made regarding management. If no other metastatic disease is present, staged resection of the primary tumor and the pulmonary nodules is a reasonable approach if complete resection can be achieved. In some cases, management of a potentially resectable primary tumor is deferred until after attempted metastasectomy, with the understanding that inability to achieve complete resection would preclude surgical management of the primary tumor.

Assessment of the ability to achieve complete resection with adequate pulmonary reserve includes appraisal of the number of nodules, consideration of the location of nodules, and estimation of the postoperative pulmonary function. For patients with unilateral involvement of three or fewer nodules and preserved pulmonary function (forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] > 80%), the assessment is straightforward. For patients with bilateral involvement of five or more nodules, the calculation is more difficult, especially if any of the lesions are central and require anatomic resection (either segmentectomy or lobectomy). There is no consensus regarding the number of nodules and the ability to achieve complete resection, but increasing numbers of pulmonary nodules are associated with a higher risk of unresectability.

The ability to achieve complete resection is considered integral to achieving the potential survival benefit of metastasectomy. CT scan of the chest is regarded as the most important preoperative radiologic examination, but its ability to detect all metastatic nodules is uncertain. Thus, some surgeons also rely on manual palpation to locate nodules that may escape CT detection. McCormack et al.2 prospectively studied the usefulness of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) versus thoracotomy for metastasectomy in 50 patients with nodules suspected to be pulmonary metastases on CT scan. They performed VATS resection of nodules identified on the CT scan and then proceeded with an open thoracotomy with bimanual palpation to find and resect undetected lesions. Of the first 18 patients, 10 were found to have malignant lesions that were missed by CT and VATS. The authors concluded that the CT scan would fail to detect all nodules and, therefore, that VATS for a metastasectomy would not result in complete resection.2 Kidner et al.3 came to the same conclusion after evaluating patients with melanoma metastases. Although single-detector row helical CT scans produce 3- to 5-mm-thick image reconstruction, thin-slice multidetector row CT scanners allowed the entire lung to be scanned with 1-mm sections in as little as 5 seconds. Kang et al.4 used the thin-slice 16-detector row CT scan preoperatively in 27 patients and compared the findings to the pathology report after resection. In nonosteosarcoma patients, the CT found 67 of 69 metastatic nodules detected by bimanual palpation intraoperatively. Based on observations like this, thin-slice CT scanners are preferred for the evaluation of pulmonary metastases.

Staging for distant metastatic disease is performed prior to pulmonary resection, based on the primary tumor. In most patients, CT of the chest and abdomen is performed to exclude liver metastases. PET scan is also commonly used to assess metastatic disease in patients with epithelial tumors and melanoma, but the effectiveness of PET is questionable.5 Mayerhogger et al. analyzed the utility of PET in a study of 181 patients with pulmonary metastases. The sensitivity of PET was 7.9% for lesions of 4 to 5 mm; 33.3% for lesions 6 to 7 mm; 56.8% for lesions 8 to 9 mm; 63.6% for 10 to 11 mm; 100% for 12 mm or higher (p < 0.0010);6 thus, the larger the lesion, the more sensitive the PET results. Any patient with pulmonary metastases who presents with neurologic symptoms should undergo magnetic resonance imaging of the brain to exclude involvement of the central nervous system.

OUTCOMES ACCORDING TO HISTOLOGY

Pulmonary metastasectomy can be considered for a variety of primary tumors, as discussed in the following sections.

COLORECTAL CANCER

COLORECTAL CANCER

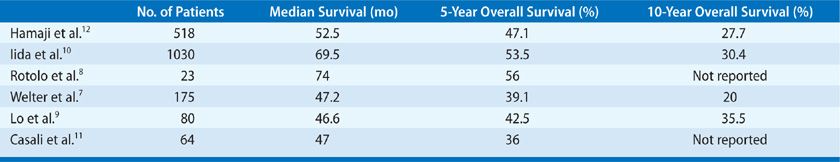

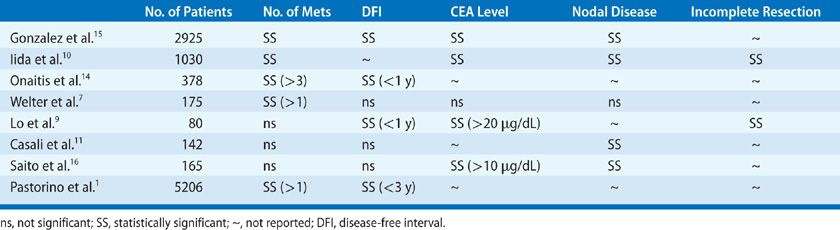

Colorectal cancer is the most common primary histology for patients with potentially resectable pulmonary metastases. Table 119-1 lists recent studies of patients with colorectal cancer who underwent resection for pulmonary metastases; 5-year survival ranged from 36% to 56%.7–12 In spite of the improved outcomes from pulmonary metastasectomy in some patients with colorectal cancer, the survival of most patients with pulmonary colorectal metastases will not be improved by pulmonary resection. Thus, much focus has gone into determining which patients with colorectal metastases to the lungs should in fact undergo surgery and which patients should not be offered futile resection. In an analysis by Phannschmidt et al.,13 none of the following factors were of prognostic value: unilateral versus bilateral disease, number of nodules, size of the dominant nodule, DFI, elevated preoperative serum level of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), use of chemotherapy, the type of surgical approach used, or repeat pulmonary resection for local recurrent disease. Recently, Iida retrospectively analyzed 1030 patients who underwent pulmonary metastasectomy for colorectal carcinoma, documenting a 5-year survival rate of 53.5% and median survival of 69.5 months. In this series, the number of nodules, tumor size, pre-op CEA, and lymph node involvement were all independent predictors of survival.10 Onaitis et al.14 found that the recurrence-free survival was 28% and overall survival was 78% at 3 years in 377 patients who underwent resection of pulmonary colorectal carcinoma metastases. DFI less than a year, female gender, and numerous metastases (>3) were independent significant predictors of recurrence.14 Gonzalez et al. recently performed a meta-analysis of 25 studies encompassing 2925 patients, and analyzed factors that impacted survival after lung metastectomy for colorectal cancer. They found that a short DFI, multiple lung metastases, positive hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and elevated prethoracotomy CEA levels were associated with poor survival.15 Review of these and other studies (see Table 119-2) demonstrates that there is not yet a consensus as to which factors have impact on survival.

TABLE 119-2 Prognostic Factors Associated with Survival after Pulmonary Metastasectomy for Colorectal Cancer (by Multivariate Analysis)

In recent years, the selection criteria for pulmonary metastasectomy have expanded to include patients with limited hepatic metastases. There has been no reported difference in outcome in patients with and without history of previously resected hepatic metastases at the time of pulmonary resection, and thus many surgeons perform pulmonary metastasectomy even in patients who have undergone hepatic resection for colorectal metastases at an earlier stage.13,14,17 Patients who undergo combination hepatic and pulmonary metastasectomy have a 30% 5-year survival rate.17 Pfannschmidt et al.13 found similar results with no significant difference in outcome observed between patients with and without history of previously resected hepatic metastases at the time of pulmonary resection with 5-year survival rates between 30% and 42%.13

SARCOMA

SARCOMA

Dear et al. analyzed 114 patients who underwent resection of pulmonary metastases for bone and soft tissue sarcomas. They found that the 5-year survival was 43% and the relapse-free survival was 19%. An incomplete surgical resection was associated with an increased risk of death, but neither the diameter of the largest resected metastasis nor a DFI of <18 months was independent prognostic factors.18 Treasure et al.19 performed a systematic review of studies involving a total of 1357 patients with pulmonary sarcoma metastases. Among patients who underwent pulmonary metastasectomy, they found a 5-year survival of 34% for patients with metastatic osteogenic sarcoma and 25% for patients with soft tissue sarcomas, as compared to a 5-year survival of 20% to 25% for all osteogenic sarcoma patients and 13% to 15% for soft tissue sarcoma patients. In this review, patients with fewer metastases and longer DFI had longer survival. These authors suggest that pulmonary resection of osteogenic sarcoma, including repeat pulmonary metastasectomy, is a safe and viable option.

RENAL CELL CARCINOMA

RENAL CELL CARCINOMA

Evidence suggests that patients with pulmonary metastases from renal cell carcinoma also derive a survival benefit from metastasectomy. Murthy et al.20 studied 92 patients who underwent pulmonary metastasectomy secondary to renal cell cancer metastases. Complete resection was achieved in 68% of the patients, with an associated 5-year survival of 45%, compared with only 8% in those who were incompletely resected. Assouad et al.21 found similar results in their evaluation of 65 patients with renal cell pulmonary metastases. The 5-year overall survival in those who underwent complete resection was 37.2%. They also found that mass size and lymph node involvement were important prognostic factors.21

MELANOMA

MELANOMA

Chua et al. evaluated 292 patients who underwent pulmonary melanoma metastasectomy. The median overall survival was 23 months and the 5-year survival was 34%. Metastasis size greater than 2 cm and positive surgical margins were independently associated with poorer progression-free survival and overall survival. The presence of more than 1 metastasis was independently associated with poorer overall survival as well.22 Petersen et al.23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree