12

Primary and secondary vasospastic disorders (Raynaud’s phenomenon) and vasculitis

Raynaud’s phenomenon

Vasospasm is the key feature of RP. Maurice Raynaud’s original description was of episodic digital ischaemia induced by cold and emotion.1 The classical manifestation of pallor preceding cyanosis and rubor reflects the initial vasospasm, followed by deoxygenation of the static venous blood (cyanosis) and then reactive hyperaemia (rubor) with the return of blood flow. The full triphasic colour change is not essential for the diagnosis of RP, and a history of cold-induced blanching with subsequent reactive hyperaemia can still reflect significant vasospasm. In addition, other stimuli can provoke an attack, for example chemicals (including drugs and those in tobacco smoke2), trauma and hormones. In addition to the digits, the vasospasm may involve the nose, tongue, ear lobes and nipples. A decrease in lung,3 oesophageal4 and myocardial5 perfusion has been shown after cold challenge, which suggests systemic vasospasm, and these patients have a higher incidence of migraine, irritable bowel syndrome and angina.6

The prevalence of primary RP varies between populations. Data from the Framingham Heart Study offspring cohort showed prevalence rates of 11% in women and 8% in men.7 Primary RP usually develops in the second or third decade. Familial and monozygotic twin studies have indicated a hereditary factor but a search for candidate genes has been unsuccessful so far.8 The prevalence of secondary RP (see below) depends on the prevalence of the underlying disorder, which itself varies between populations.

Inconsistent terminology is a major problem for clinicians managing RP. Europeans use RP as a blanket term for all cold-related vasospasm, with secondary Raynaud’s syndrome (RS) being associated with another disease, and primary Raynaud’s disease (RD) where it occurs in isolation. However, American and Australasian researchers use the syndrome and phenomenon interchangeably,9 and differentiate the types of RP by indicating whether it is primary RP or secondary RP. The former classification has been used in this chapter.

Many patients with mild disease never present to their general practitioners but of those who do, most will have primary RD. Patients with more severe disease are likely to be referred to a hospital specialist, and an early marker for secondary RS is the severity of vasospastic attacks,10 although the RP may precede associated systemic disease by more than 20 years.11 Hospital practitioners are therefore more likely to see a higher proportion of RS, and the important challenge is to differentiate between the primary and secondary conditions in order to facilitate early management of the underlying associated disorder.

The secondary associations of RS are shown in Box 12.1. Of the connective tissue diseases (CTDs), systemic sclerosis is the most frequent association. In the hyperviscosity syndromes, such as myeloma, the prevalence is similar to the normal population but the symptomatology tends to be more severe.

Occupational RS is also well recognised and a relatively common form is hand–arm vibration syndrome (HAVS; previously known as vibration white finger). As the name suggests, it occurs in workers exposed to vibrating instruments such as chainsaws, pneumatic road drills and buffing machines. An estimated 4.2 million men and 667 000 women in Great Britain have occupational exposure to hand-transmitted vibration.12 Before these tools were regulated 90% of exposed workers developed symptoms of HAVS. Among American shipyard workers, 71% of full-time pneumatic grinders complained of white fingers13 and in Japan 9.6% of forest workers had symptoms of this syndrome.14

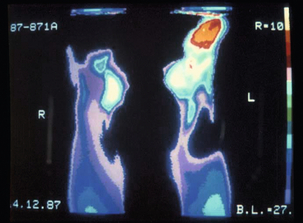

The duration of exposure is important, with a latent period of often less than 5 years of full-time work. The severity of symptoms correlates with the length of exposure.15 Vasospasm is not limited to the hands and has also been described in the toes (Fig. 12.1).16 It is likely that vibration-induced damage of the endothelium underlies this condition.17 In approximately one-quarter of cases, the symptoms may resolve if a job change is effected early in the course of the disease.18

In the UK, HAVS has been a proscribed industrial disease since 1985. Patients may be eligible for industrial injuries disablement benefits if they fulfil certain criteria.19 Specific daily time limits for different machines have been proposed and are being implemented opportunistically, often by use of a points system.

Atherosclerotic obstructive arterial disease is a common cause of RP in those over 60 years of age, particularly in men, and screening and treatment of known risk factors, such as hyperlipidaemia, are recommended. Various drugs may precipitate or exacerbate RP (e.g. beta-blockers for angina) and alternative drug therapies may be more appropriate (e.g. calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine). Vasospasm is also a feature of reflex sympathetic dystrophy and thoracic outlet syndrome, particularly occurring in the presence of a cervical rib (see Chapter 11).

Pathophysiology

Neurogenic

Most studies have focused on the peripheral nervous system. In patients with RP, α-adrenergic receptor sensitivity and density are increased20 and the responsiveness of β-adrenergic presynaptic receptors in the peripheral vessels is also increased.2 It has been suggested that the central nervous system may contribute to vasospasm but this is a difficult area to research and there is little direct evidence to support its influence.

Interactions between blood and blood vessel walls

Microcirculatory flow depends on a functioning endothelium, plasma factors and the cellular elements of blood. Activated platelets aggregate and form clumps that can obstruct flow. They may also release vasoconstrictors such as thromboxane A2 and serotonin, causing further platelet aggregation. Red blood cells (RBCs) appear less deformable in RP and cold temperatures further increase RBC stiffness.21 Rigid RBCs and white blood cells (WBCs) may impede the microcirculation, and activated WBCs aggregate and adhere within the microcirculation and can narrow the vascular lumen. Additionally, WBC activation increases the formation of free radicals, which may be prothrombotic.22 Elevated fibrinogen and globulin levels increase plasma viscosity and reduce blood flow. Increased platelet aggregation, rigid RBCs and activated WBCs have all been reported in patients with RS, together with raised plasma viscosity and reduced fibrinolysis.23

The intact endothelium is a functioning organ that produces many substances important in maintaining blood flow. Damage to it may impair blood flow in RP. Factor VIII von Willebrand factor (VWF) antigen is released following vascular damage and is increased in patients with RP.24 VWF is active in the clotting cascade and platelet activation and may contribute to reduced blood flow. Tissue plasminogen activator is active in fibrinolysis and levels are reduced in RP, with a subsequent reduction in fibrinolysis.23

Endothelial vasoconstrictor/vasodilator production may also be impaired.25–32 Most of these abnormalities are seen in patients with RS except for the increase in VWF, which occurs in the primary disease also. It is possible therefore that these are a consequence rather than the cause of the disorder. Nevertheless, they may still augment the impairment of blood flow and their correction by drug therapy may produce clinical benefit.

Inflammatory and immunological mechanisms

Most cases of severe RS occur when associated with CTD, and disordered immunology and inflammation are found in these patients. Interestingly, however, abnormal WBC behaviour also occurs in HAVS,33,34 which has no clear immunological/ inflammatory basis. The interested reader is referred to the scientific literature.35–37

Clinical features

The initial features of demarcated blanching of extremities produced in response to cold, temperature change and emotion are episodic. Digital artery spasm is the cause of this pallor, although many people may complain of cold hands with some mild poorly delineated colour changes. They do not necessarily have RP but probably cold-induced closure of the arteriovenous shunts in the skin, which decreases cutaneous blood flow and limits body heat loss. Patients with RP subsequently experience the cyanotic phase and/or the redness of the reactive hyperaemia phase. This last phase may be associated with rewarming paraesthesia and pain. RP is therefore characterised by being biphasic or triphasic, and usually affects the fingers and toes though finger symptoms tend to be more prominent. This may be asymmetrical in that, for example, only one or two digits may be affected on each hand, although all digits may be equally affected. As documented earlier, other extremities such as the ears, tongue and nose may also be affected, but a bluish discoloration in isolation is due to acrocyanosis and not RP. The occurrence of other skin-related problems (e.g. digital ulcers (Fig. 12.2) and recurrent chilblains), an onset in children under 10 years of age, an older adult onset (> 30 years) and perennial attacks suggest secondary RP.

Investigations

Nail-fold capillaroscopy can be performed using an ophthalmoscope at high power. Normal vessels are not visualised but abnormally enlarged vessels, for example as seen in systemic sclerosis, will be seen quite easily (Fig. 12.3). These may also be examined by formal high-power microscopy but it should be noted that nail-fold changes also occur with trauma and in diabetes mellitus. The combination of abnormal nail-fold vessels and an abnormal immunological test has a 90% prediction value for later CTD.9 Using structured classification systems, nail-fold patterns may be useful in assessing progression of the CTD.39

Other tests, such as laser Doppler flowmetry, are used as research tools but are not helpful in making the diagnosis.41

Management

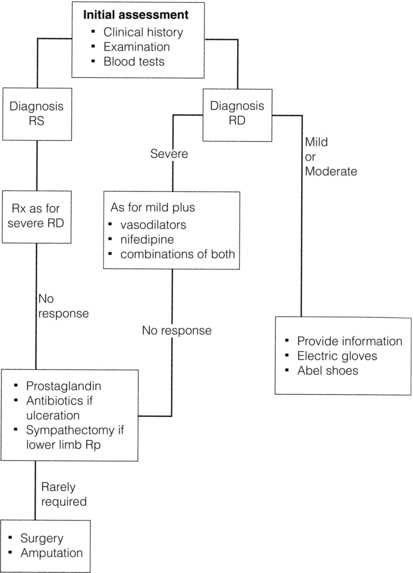

A proportion of patients with mild disease will not require drug treatment. Associated disorders such as hypothyroidism should be treated and causative drug therapy (e.g. beta-blockers) changed. Good symptomatic relief can be achieved in many patients despite the current lack of cure. A suggested management plan is shown in Fig. 12.4.

Drug therapy

This should be offered when symptoms are severe enough to interfere with work or lifestyle. Most patients with RS and some with RD will fall into this category. A selection of the drugs used in the treatment of RP is shown in Box 12.2.

Calcium channel blockers: These drugs are vasodilatory. Nifedipine is the gold standard and the most frequently prescribed drug, and has additional antiplatelet42 and anti-WBC activity. However, its use is limited by the vasodilatory effects of flushing, headache and ankle swelling. These will be attenuated by using the slow-release, or ‘retard’, preparations and starting with 10 mg once daily, gradually increasing to a maximum of 20 mg t.d.s. if required. Apart from ankle swelling, the vasodilatory adverse effects often abate with continued use. Nifedipine has no licence for use in pregnancy and patients should be advised accordingly. Other potentially useful calcium blockers include amlodipine,43 diltiazem44 and isradipine.45 These tend to have fewer vasodilatory effects but at the expense of efficacy. Verapamil and ketanserin are ineffective.

Other vasodilators: Naftidrofuryl oxalate (Praxilene) is a mild peripheral vasodilator with a serotonin receptor antagonist effect. An oral dose of 200 mg t.d.s. has been evaluated in many studies and mild improvement can be expected in terms of severity of pain and duration of attacks.

Prostaglandins: Prostaglandins such as PGI2 and PGE1 have potent vasodilatory and antiplatelet effects but are both very unstable and require intravenous administration. Iloprost is a stable prostacyclin analogue that is effective in RP.46 It is given intravenously for 6 hours daily for 3–5 days per treatment. The dose is gradually increased during each 6-hour period to a maximum tolerated dose, which should never be greater than 2 ng/kg per min. It is often less than this, particularly in women, because of flushing, headache or rarely hypotension. The same maximum dose is used each day. It is probably equipotent with nifedipine but remains a second choice in Europe because of its parenteral mode of administration and lack of licence in some countries. A study of oral iloprost in Raynaud’s syndrome47 has been encouraging, and a trial in those with RP secondary to systemic sclerosis has shown a significant benefit compared to placebo.48 Oral beraprost seems to be ineffective.

Other drugs: Case reports and pilot studies suggest interesting areas for future work. Sildenafil improved pulmonary hypertension and peripheral blood flow in a patient with scleroderma-associated lung fibrosis and RP,49 while Ginkgo biloba extracts50 may also be effective in some cases. Cilostazol, a synthetic phosphodiesterase III inhibitor that reversibly inhibits platelet aggregation, is used for the treatment of intermittent claudication, and was tested in a randomised controlled trial in RP patients. Treatment was associated with vasodilation of the brachial arteries and conduit vessels.51 However, the drug had no effects on microvascular blood flow or on the frequency and severity of RP attacks in both primary and secondary RP.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree