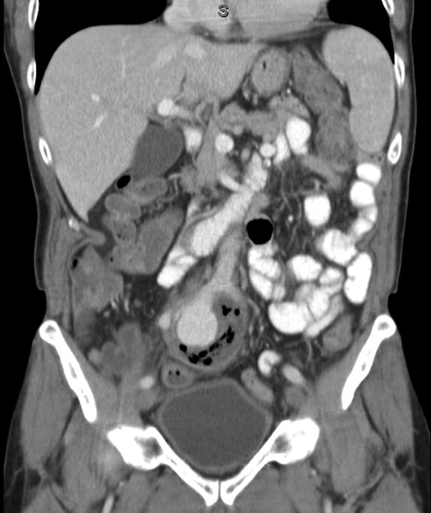

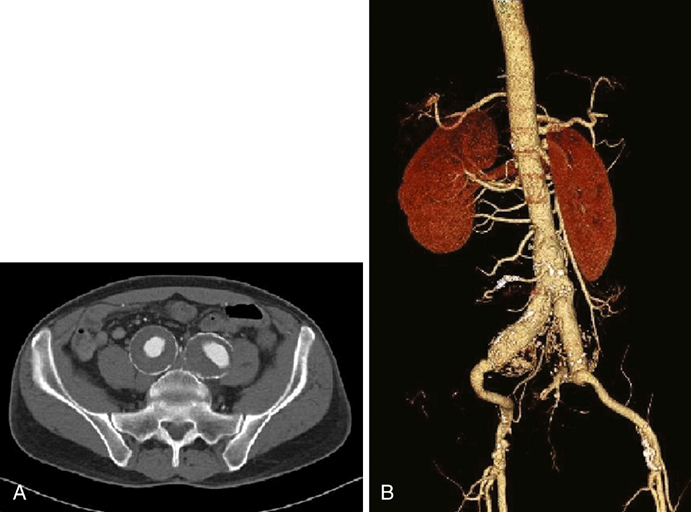

The most common etiology for IAAs is atherosclerotic disease. Other etiologies that have been reported include mycotic (Figure 1) or false aneurysms secondary to syphilis, tuberculosis, and osteomyelitis. Other conditions associated with IAAs include trauma, fibromuscular dysplasia, Behçet’s disease, collagen defects (such as Marfan’s and Ehlers–Danlos syndromes), cystic medial necrosis, and Kawasaki’s syndrome. Reports of IAAs have also been reported after pregnancy, particularly following traumatic childbirth or forceps delivery. CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide a more accurate and detailed anatomy of IAAs, have less interobserver variability, and provide anatomy of surrounding structures. Multislice CT scanning (Figure 2) has rapid and accurate image acquisition, although it may be affected by foreign objects (such as metal hip prostheses) and it requires intravenous contrast agents. MRI is limited by its longer acquisition time, a patient’s ability to tolerate an MRI (e.g., claustrophobia, pacemakers, implanted metallic objects), and potential adverse events such as systemic nephrogenic sclerosis from the use of contrast agents. Nevertheless, CT and MRI are particularly useful in preoperative planning to determine if a patient may be a candidate for an endovascular intervention. Formal catheter-based angiography has little role in diagnosing IAAs, especially those with mural thrombus, although it may be useful in preoperative planning.

Natural History and Open Treatment of Isolated Iliac Artery Aneurysms

Epidemiology

Diagnosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine