Mitral Valve Repair for Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation

Vincent Chan

Javier G. Castillo

David H. Adams

INTRODUCTION

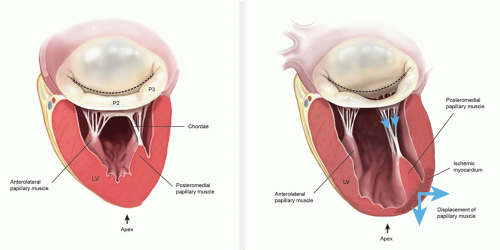

Ischemic mitral regurgitation (MR) is a mechanical complication of coronary artery disease. Most commonly, ischemic MR is due to chronic left ventricle remodeling following myocardial infarction. The resulting papillary muscle displacement leads to tethering of the mitral valve leaflets and varying degrees of annular dilatation (Fig. 44.1). This entity should be distinguished from coronary artery disease and concomitant MR due to other causes such as degenerative mitral valve disease. Naturally, the repair techniques and longterm outcomes following repair are very different depending upon the underlying etiology. Acute ischemic MR is rare and is secondary to papillary muscle rupture or chordal elongation.

Ischemic MR is common and associated with significant morbidity and mortality. MR is observed in approximately 10% of patients undergoing cardiac catheterization and may be associated with 40% mortality within the first year of diagnosis. The increasing prevalence of coronary artery disease has resulted in a rise in the number of patients with ischemic MR requiring surgery. Despite advances in medical and surgical management, longitudinal data have shown poor survival for patients with ischemic MR compared with patients who present with MR due to other causes. Nevertheless, new technologies and recent studies have provided new insights into this challenging surgical problem. In this chapter, we review ischemic MR with regard to its pathophysiology, clinical presentations, diagnosis, and management.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGIC TRIAD OF MITRAL REGURGITATION

MR is defined as the backward flow of blood in systole from the left ventricle into the left atrium via the mitral valve. Minimal lesions might cause MR by reducing mitral leaflet coaptation. Therefore, a careful interrogation (identification, localization, and magnitude) for mitral lesions is essential to determine the chances of successful valve repair and to proceed with a tailored therapeutic plan for each patient. Three decades ago, Carpentier described a systematic analytic approach to patients with MR known as the “pathophysiologic triad of mitral valve regurgitation.” The triad emphasizes the importance of distinguishing between the medical conditions causing MR (etiology), the resulting lesions, and finally how these lesions affect leaflet motion (dysfunction).

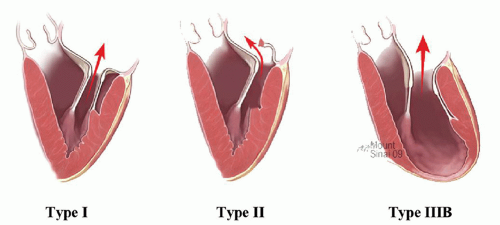

Patients with type I dysfunctions have normal leaflet motion, and MR is due to annular dilation or leaflet perforation (Fig. 44.2A). There is increased leaflet motion in patients with type II dysfunction, with the free edge of at least one of the leaflets overriding the plane of the annulus during systole (Fig. 44.2B). Lesions responsible for type II dysfunction include chordal elongation, chordal rupture, and papillary muscle rupture. Type III dysfunction refers to restricted leaflet motion, with the free margin of one or both leaflets pulled below the plane of the annulus into the left ventricle, thereby reducing leaflet mobility and coaptation during systole and leading to MR. Patients with type IIIa dysfunction have restricted leaflet motion during both diastole and systole, as in the case with rheumatic valve disease. Type IIIb dysfunction is caused by restricted leaflet motion during systole, which occurs in the setting of left ventricular dysfunction and dilation; apical and posterolateral papillary muscle displacement causes this type of valve dysfunction (Fig. 44.2C).

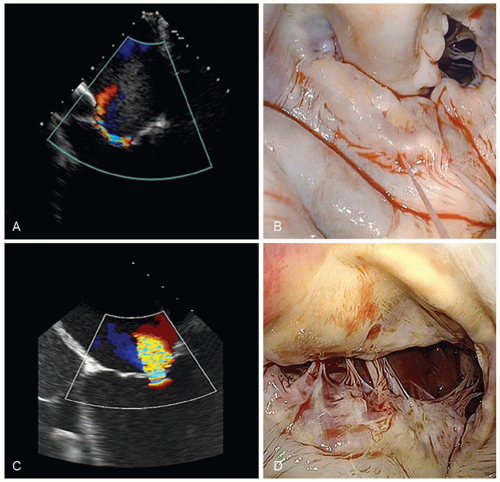

Ischemic MR can result from type I, II, or IIIb dysfunction (Table 44.1). Isolated type I dysfunction with annular dilation is uncommon but may occur in basal myocardial infarction. An associated type I lesion in the setting of a primary type IIIb lesion is a common finding in ischemic MR, but the amount of annular dilatation is often less than that seen in degenerative disease. Type II dysfunction after myocardial infarction results from papillary muscle rupture, which usually involves the posteromedial papillary muscle or occurs when a fibrotic papillary muscle elongates and causes leaflet prolapse, particularly in the commissural area (this a rare lesion). In rare instances, an isolated chordal rupture can cause type II dysfunction. Carpentier’s type IIIb dysfunction is the most common and significant form of ischemic MR.

NATURAL HISTORY OF MITRAL REGURGITATION

Ischemic MR following myocardial infarction is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Notably, more adverse events are observed with increasing MR severity. Data from the Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications study showed that in patients following ST elevation MI, the absence of MR was associated with an 1.4% 30-day mortality rate compared with 3.7% in patients with mild MR and 8.6% in patients with moderate-to-severe MR. Late survival is also worse with a reported 5-year total mortality and cardiac mortality of 62% and 50%, respectively, for patients with ischemic MR compared with 39% and 30%, respectively, for patients without ischemic MR. Beyond survival, ischemic MR is associated with more frequent hospitalization for congestive heart failure, with 30% of patients requiring hospital admission within 3 years of diagnosis.

TYPE IIIB ISCHEMIC MITRAL REGURGITATION

Pathophysiology

Normal mitral valve function involves a complex three-dimensional interaction

among the leaflets, annulus, subvalvular apparatus, and left ventricular wall. Several anatomic and pathophysiologic changes are associated with the pathogenesis of ischemic MR. They include ventricular changes (wall-motion abnormalities and/or dilation with increased sphericity), subvalvular changes (papillary muscle infarction, displacement, or tethering), and annular changes (distortion, dilation). The initial insult in chronic ischemic MR is due to remodeling of the left ventricle after myocardial ischemia or infarction. This remodeling converts the shape of the left ventricle from ellipsoidal to spherical, which leads to regional annular and subvalvular distortion and ultimately to poor leaflet coaptation. It appears that left ventricular sphericity is more important than the actual ventricular volume or ejection fraction in the progression of ischemic MR. The primary ventricular alteration leading to ischemic MR is papillary muscle displacement. The pattern of displacement is complex and cannot simply be described as apical tethering. The papillary muscle tips are displaced away from the midseptal (anterior) annulus, that is, posterolaterally, apically, and away from each other. The tethering distance has been shown to correlate with the severity of ischemic MR. Papillary muscle tethering leads to apical tenting of the leaflets (restriction of the motion of the free margins of the leaflets), which prevents them from rising to the plane of the annulus to coapt with one another (Fig. 44.3). Recent animal studies also suggest that the remodeling process accelerates as the degree of MR increases. Clinically, this tethering of the secondary chordae can be seen echocardiographically in the form of the “sea-gull” deformation of the body of the leaflet.

among the leaflets, annulus, subvalvular apparatus, and left ventricular wall. Several anatomic and pathophysiologic changes are associated with the pathogenesis of ischemic MR. They include ventricular changes (wall-motion abnormalities and/or dilation with increased sphericity), subvalvular changes (papillary muscle infarction, displacement, or tethering), and annular changes (distortion, dilation). The initial insult in chronic ischemic MR is due to remodeling of the left ventricle after myocardial ischemia or infarction. This remodeling converts the shape of the left ventricle from ellipsoidal to spherical, which leads to regional annular and subvalvular distortion and ultimately to poor leaflet coaptation. It appears that left ventricular sphericity is more important than the actual ventricular volume or ejection fraction in the progression of ischemic MR. The primary ventricular alteration leading to ischemic MR is papillary muscle displacement. The pattern of displacement is complex and cannot simply be described as apical tethering. The papillary muscle tips are displaced away from the midseptal (anterior) annulus, that is, posterolaterally, apically, and away from each other. The tethering distance has been shown to correlate with the severity of ischemic MR. Papillary muscle tethering leads to apical tenting of the leaflets (restriction of the motion of the free margins of the leaflets), which prevents them from rising to the plane of the annulus to coapt with one another (Fig. 44.3). Recent animal studies also suggest that the remodeling process accelerates as the degree of MR increases. Clinically, this tethering of the secondary chordae can be seen echocardiographically in the form of the “sea-gull” deformation of the body of the leaflet.

Annular dilation is a common associated finding in chronic ischemic type IIIb MR. However, the degree of dilation can vary and does not necessarily correlate with the degree of MR. Annular flattening of the saddle also occurs in ischemic MR. Laboratory data support the notion that annular dilation is not a fundamental component in the pathogenesis of ischemic MR. It has been demonstrated that mild degrees of annular dilation observed during acute occlusion of the left anterior

descending or distal left circumflex in an animal model did not result in ischemic MR. The aforementioned changes in left ventricular geometry, papillary muscle position, and annular dimensions interact to result in poor leaflet coaptation during systole, which is the final common pathway for type IIIb ischemic MR.

descending or distal left circumflex in an animal model did not result in ischemic MR. The aforementioned changes in left ventricular geometry, papillary muscle position, and annular dimensions interact to result in poor leaflet coaptation during systole, which is the final common pathway for type IIIb ischemic MR.

Table 44.1 Pathophysiologic Triad in Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Clinical Presentation

Type IIIb ischemic MR can occur in an acute or chronic setting. Acute postinfarction ischemic MR, without papillary muscle rupture, can be documented in many patients by physical examination, ventriculography, or echocardiography. Moderate-to-severe MR is present in up to 13% of these patients. Acute severe type IIIb ischemic MR often presents with the sudden onset of shortness of breath and/or angina. In most patients, this incident is preceded by an acute myocardial infarction, which may be silent particularly in diabetic patients. A minority of patients will present with symptoms of severe heart failure and/or low cardiac output. Although MR resolves over time in some patients, it will persist in others and lead to chronic postinfarction ischemic MR. In these patients, chronic ischemic MR will appear up to 6 weeks (median 7 days) after myocardial infarction as the left ventricle remodels. Risk factors for postinfarction ischemic MR include advanced age, female gender, prior acute myocardial infarction, large infarct size, recurrent ischemia, multivessel coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure.

In patients with chronic ischemic MR, two clinical scenarios are commonly encountered. Patients may present with moderate-to-severe MR, symptoms of congestive heart failure, or worsening left ventricular function, and are referred primarily for mitral valve intervention. The preoperative coronary angiogram in these patients shows significant multivessel coronary artery disease, which may or may not have lead to symptoms. These patients often have clear evidence of prior myocardial infarction and at least moderate left ventricular dysfunction. Other patients present with symptomatic multivessel coronary artery disease and are referred for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) with a varying degree of MR on preoperative ventriculography or echocardiography. An acute coronary syndrome or chronic stable angina is often the dominant presenting symptom in these patients. In addition, they may present with symptoms of shortness of breath and/or congestive heart failure.

Diagnosis

Patients often have changes on their electrocardiogram (ECG), and a prior myocardial infarction may be noted in >80% of patients with chronic ischemic MR. When ECG changes are noted, evidence of a prior inferior wall infarct is more common than an anterior or a lateral infarct. Most patients are in sinus rhythm; however, in patients with left atrial enlargement, p-wave abnormalities and atrial fibrillation may occur. Conduction abnormalities are uncommon in these patients. In the acute setting, the chest radiograph may show pulmonary edema. With disease progression, enlargement of the cardiac silhouette (left atrial enlargement, ventricular dilation) is a common finding. Cardiac catheterization will typically show multivessel disease and, likely, segmental wall motion abnormalities on ventriculography.

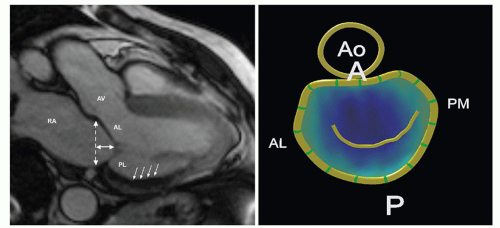

Two-dimensional echocardiography/Doppler is essential in determining the MR mechanism and severity, along with the function of the left ventricle. The severity of MR can be determined by semiquantitative measurements using jet geometry and area in multiple views. With restricted leaflet motion (type IIIb), the direction of the jet is often toward the restricted leaflet, or central if associated annular dilation is present. In this context, imaging has revealed two major patterns of leaflet tethering in the setting of ischemic MR: symmetric and asymmetric. Asymmetric tethering is defined by the displacement of the posteromedial papillary muscle, causing posterior leaflet restriction and leading to an eccentric jet toward the posterior wall of the left atrium. As opposed to asymmetric tethering, symmetric tethering results from the displacement of both papillary muscles, and a central jet is typically observed. This symmetric pattern is the one observed in the setting of functional MR secondary to overlapping dilated cardiomyopathy (Fig. 44.4). The severity of MR is quantified via calculation of regurgitant volume (the difference between the

mitral and aortic stroke volumes) and effective regurgitant orifice (ratio of regurgitant volume-to-regurgitant time velocity integral). Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) can be used to further delineate the mechanism of MR; however, afterload reduction associated with general anesthesia is known to ameliorate the intensity of MR.

mitral and aortic stroke volumes) and effective regurgitant orifice (ratio of regurgitant volume-to-regurgitant time velocity integral). Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) can be used to further delineate the mechanism of MR; however, afterload reduction associated with general anesthesia is known to ameliorate the intensity of MR.

SURGICAL INDICATIONS

Severe Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree