Mitral Valve Repair

Lawrence H. Cohn

R. Scott McClure

Mitral valve repair is one of the most important technical advances in cardiac surgery over the past 35 years and is the treatment of choice for most conditions of the mitral valve, most notably the prolapsed valve with myxomatous degeneration. This chapter outlines the current concepts and reparative techniques for the myxomatous degenerated mitral valve. Elements of the pathoanatomy and principles of repair will be reviewed followed by a detailed explanation of the surgical techniques used and refined at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital by the lead author over a 40-year career. Select adjunct techniques popularized at other major centers throughout the world are also discussed.

DEVELOPMENT OF TECHNIQUES OF MITRAL VALVE REPAIR

Elliott Carr Cutler at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital did the first successful operative repair of the mitral valve in 1923. The surgery was performed on a 12-year-old girl diagnosed with severe rheumatic mitral stenosis. Using a neurosurgical tenotomy knife via a median sternotomy, Cutler, boldly and ingeniously inserted the knife transapically into the left ventricle of the beating heart, incising each fibrotic commissure in a blinded manner. Isolated successes with this operation were rare. It was not until after World War II, when Harken in Boston and Bailey in Philadelphia popularized the method of closed mitral commissurotomy for mitral stenosis using the finger fracture technique, that reasonable surgical successes were achieved for the management of what was inevitably a terminal disease. For the next 25 years, until the early 1970s, the closed mitral commissurotomy procedure was one of the most widely utilized techniques to treat and relieve mitral stenosis.

Similar to severe mitral stenosis, severe mitral regurgitation was also recognized early on to incur adverse outcomes prompting similar though more sporadic attempts at surgical correction. Yet unlike the surgical successes garnered with mitral stenosis, mitral regurgitation generated little in the way of innovative progress or reproducible surgical techniques until the development of the heart-lung machine in the mid-1950s. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, several suture annuloplasty techniques were developed to relieve mitral regurgitation with a modicum of success. One of the more successful attempts to relieve mitral regurgitation at the time was a technique developed by Harold Kay in Los Angeles who obliterated the commissures using a sequence of mattress sutures. A circular technique developed by Paneth and DeVega, involving a circumferential suture around the annulus, also aided in the early attempts at mitral valve repair. In the early 1960s, Dwight McGoon proposed a reparative technique for the degenerative prolapsed mitral valve with ruptured chordae that involved resecting a small segment of the mitral leaflet from the mitral valve. He rationalized that small resections of the mitral leaflet would prevent overall distortion of the valve and in the few cases where it was trialed the technique proved successful. However, with the advent of prosthetic devices to replace the mitral valve in the early 1960s, efforts to repair the mitral valve quickly waned with mitral valve replacement emerging as the preferred treatment choice for mitral regurgitation at the majority of institutions.

One of the ironies of the early 1960s was that most surgeons of the era believed it prudent to cut the papillary muscle and all chordal attachments to the mitral leaflets to ensure an anatomically secure mitral valve replacement. It is now recognized that utilizing chordal sparing techniques to preserve the subvalvular apparatus and annular-papillary continuity during mitral valve replacement retains left ventricular geometry. This portends to improve left ventricular mechanics and left ventricular function. Late cases of severe left ventricular decompensation and cardiomyopathy began to emerge in patients having undergone corrective surgery for mitral regurgitation where the chordal attachments were excised. Poor outcomes in these early experiences with corrective surgery for mitral regurgitation caused many surgeons to retreat from such operations. And cardiologists for their part became reluctant to refer such patients to surgery as a treatment option. A lack of appreciation for the importance of the subvalvular integrity when performing mitral surgery, which resulted in suboptimal outcomes, in addition to the prevailing yet erroneous “pop off ” valve theory of the time, sustained the reluctance to intervene on the regurgitant mitral valve for many years. The “pop off ” theory was the misconception that if a patient had progressed to having left ventricular dysfunction secondary to mitral regurgitation, the regurgitant valve was now a necessary evil, as it became a “pop off ” valve into the left atrium that relieved stress on the failing heart. Any effort to correct the mitral valve in this situation was presumed to impart further stress on the already failing ventricle and thus cause deleterious effects. These two key misconceptions, removal of the subvalvular apparatus and the fallacious “pop off ” construct, stymied advancements in surgery to treat mitral regurgitation well into the 1980s.

The late 1970s and early 1980s heralded a new development in mitral valve reconstructive surgery with the invention of prosthetic remodeling annuloplasty rings. The works of Alain Carpentier and Carlos Duran, pioneering surgeons independently credited with first implanting prosthetic rings during mitral valve reconstructive operations to refashion and remodel the mitral annulus, were seminal developments. The concept of implanting a prosthetic remodeling annuloplasty ring enabled mitral valve reparative procedures to be performed in a reproducible manner by surgeons worldwide. Along with the introduction of prosthetic rings to aid in annular remodeling, these two surgeons are credited with outlining the basic principles of mitral valve repair for the generations of cardiac surgeons to follow. In 1983, as an honored lecturer of the American Association for Thoracic Surgeons, Dr. Carpentier gave the now classic lecture entitled, “The French Correction,” outlining the basic principles of repair for the prolapsed mitral valve and emphasized the importance of an annuloplasty ring. This lecture helped to stimulate the thought process of the cardiac surgery community regarding the surgical treatment of patients with mitral regurgitation. A number of surgeons have subsequently developed rings of different caliber, consistency, and shape. Though the multitude of rings now available each profess their advantages over one another, the basic fundamental principles to mitral valve repair remain faithful to the initial tenets outlined by Carpentier and Duran, with a key tenet being the integral importance of an annuloplasty ring to remodel the annulus for long-term success. A commitment to annuloplasty ring implantation, more so than the type of ring implanted, is a far more important factor for successful outcomes.

PRINCIPLES OF MITRAL VALVE REPAIR

The principles of repair for the mitral valve have evolved with experience for each of the four etiologies of mitral regurgitation: rheumatic, endocarditic, ischemic, and myxomatous. Regardless of the etiology, the principles are basically the same: (1) create apposition of the anterior and posterior leaflets during systole, (2) increase valve mobility, (3) prevent valve stenosis, (4) reduce annular dilatation, (5) remodel the annulus, (6) prevent systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve into the left ventricular outflow tract causing obstruction. Whereas the focus of this chapter is primarily the myxomatous mitral valve, other chapters of this textbook very explicitly outline reparative techniques for rheumatic, ischemic, and endocarditic mitral valve disease.

REPARATIVE TECHNIQUES FOR THE MYXOMATOUS DEGENERATED MITRAL VALVE

The following principles of mitral valve repair for degenerative mitral valve disease are now commonly accepted: (1) apposition of the posterior and anterior leaflets during systole, (2) reduced height of the posterior leaflet such that the prolapsing segment of the posterior leaflet is obliterated or reduced causing the overall height of the leaflet to be shortened, (3) stabilization of the anterior leaflet by repairing and replacing ruptured chords or shortening very elongated chords, (4) remodeling the annulus, which is distorted and distended using an annuloplasty ring. The annuloplasty ring may be a full encircling ring or a partial C-band, either rigid or flexible.

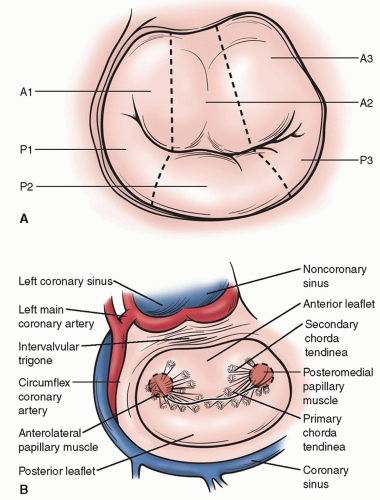

Conventional terminology used to describe the normal segments of the posterior and anterior mitral valve leaflets are depicted in Figure 42.1A. The surgical anatomy of the mitral valve and adjacent structures are illustrated in Figure 42.1B.

Apposition of the anterior and posterior leaflets in systole is fundamental to providing a durable mitral valve repair. The optimum level at which the leaflet apposition creates a tight coaptation point preventing any leakage across the valve can be determined by the “Carpentier” reference point in unaffected areas of the posterior leaflet in comparison to the anterior leaflet. Once this reference point has been identified, adjacent segments of the mitral leaflets where the reference point has not been adhered to, denotes those areas of the valve

where alterations to the height of the leaflets need to occur so as to restore a single uniform plane of apposition. Typically, the surgeon will reduce the height of the posterior leaflet letting it serve as a “doorstop” for the anterior leaflet; the “height” refers to the distance from the base of the leaflet at the annulus to the leading edge of the leaflet at the free margin. Re-creating a uniform plane of apposition across the entire mitral valve eradicates the persistent leak and results in successful repair.

where alterations to the height of the leaflets need to occur so as to restore a single uniform plane of apposition. Typically, the surgeon will reduce the height of the posterior leaflet letting it serve as a “doorstop” for the anterior leaflet; the “height” refers to the distance from the base of the leaflet at the annulus to the leading edge of the leaflet at the free margin. Re-creating a uniform plane of apposition across the entire mitral valve eradicates the persistent leak and results in successful repair.

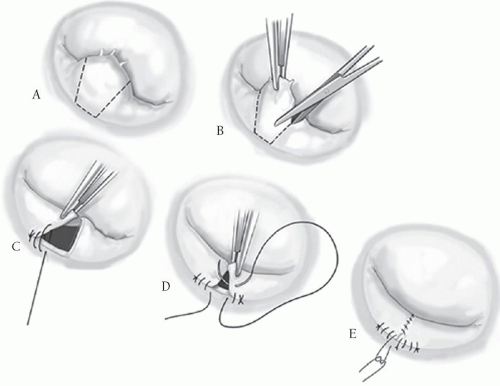

MITRAL VALVE REPAIR TECHNIQUES FOR ISOLATED POSTERIOR LEAFLET PROLAPSE

In patients with myxomatous disease of the mitral valve, more than 80% of the patients have pathoanatomy requiring repair of the posterior leaflet, predominantly P2, having either markedly elongated chords or actual rupture and flail chordae (Fig. 42.2A). There are many different techniques to repair this defect. Our preference is a limited resection of the flail segment, removing the minimal number of adjacent chordae and only as much of the supporting structures of the posterior leaflet as is necessary. A silk suture is placed at the middle of the offending segment and the area is excised in a trapezoidal shape, with the narrowest portion of the trapezoid at the annulus, to ensure maximum preservation of adjacent chordae. Once the flail segment is excised, there is a “drawing down” of the adjacent parts of P2 with two running 4-0 monofilament sutures, bringing the two remaining parts of the leaflet together (Fig. 42.2B-E). This is a “modified” leaflet advancement technique promoted by the lead author. The classic leaflet advancement technique popularized by Carpentier is shown in Figure 42.3. The drawback here is that one must incise the posterior leaflet completely off the annulus and then re-suture the leaflet back onto the annulus. As the two segments of the posterior leaflet are re-sutured, they are advanced medially toward the midpoint of the posterior annulus such that the two leaflet segments meet in the middle, reducing leaflet height in the process. Complete removal of the leaflet from the posterior annulus can be a daunting task for the less experienced surgeon. The “modified” advancement technique achieves the same goal as the classic Carpentier technique yet is more simplistic, less time-consuming, and more easily taught and adopted by cardiac surgeons with a more modest mitral valve case volume.

With either of these techniques, again, approximate the residual posterior leaflet segments to the annulus using two running 4-0 monofilament sutures advanced medially toward the center of the annulus. Then, with these sutures held on tension approximate the two residual leaflet segments to one another. With a double-armed 4-0-monofilament suture, begin at the leading edge of the leaflets and tie four knots such that equal lengths of the suture reside on each side of the knot. The two lengths of the suture are then run back toward the annulus suturing the leaflet edges together and tying a knot with the adjacent advancement sutures previously left untied and held on tension. The adjacent leaflet segments are brought together with a double over-and-over technique. From the leading edge of the leaflet, the first suture is a running mattress and the second suture is a simple over-and-over running stitch to prevent any chance of dehiscence. We do not use pledgets of any kind on the mitral valve leaflets, as they tend to produce scarring and may provide a site for potential thromboemboli. Once the posterior leaflet is refashioned, the valve is then tested for competency. Even without a supporting ring the valve is usually competent in 90% of patients at this point. An encircling annuloplasty ring or partial C-band is then fixated to the annulus to complete the repair. Of note, though we advocate the use of the “modified” advancement technique for its simplicity, in the case of true Barlow’s syndrome where all segments of the posterior leaflet are elongated, the classic Carpentier technique is required (Fig. 42.3), as the “drawing down” of P2 will not adequately reduce the height of the posterior leaflet sufficiently in this situation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree