Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have been used in clinical practice in the United States for the last 4 to 6 years. Although DOACs may be an attractive alternative to warfarin in many patients, long-term outcomes of use of these medications are unknown. We performed a propensity-matched analysis to report patient important outcomes of death, stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA), bleeding, major bleeding, and dementia in patients taking a DOAC or warfarin. Patients receiving long-term anticoagulation from June 2010 to December 2014 for thromboembolism prevention with either warfarin or a DOAC were matched 1:1 by index date and propensity score. Multivariable Cox hazard regression was performed to determine the risk of death, stroke/TIA, major bleed, and dementia by the anticoagulant therapy received. A total of 5,254 patients were studied (2,627 per group). Average age was 72.4 ± 10.9 years, and 59.0% were men. Most patients were receiving long-term anticoagulation for AF management (warfarin: 96.5% vs DOAC: 92.7%, p <0.0001). Rivaroxaban (55.3%) was the most commonly used DOAC, followed by apixaban (22.5%) and dabigatran (22.2%). The use of DOACs compared with warfarin was associated with a reduced risk of long-term adverse outcomes: death (p = 0.09), stroke/TIA (p <0.0001), major bleed (p <0.0001), and bleed (p = 0.14). No significant outcome variance was noted in DOAC-type comparison. In the AF multivariable model patients taking DOAC were 43% less likely to develop stroke/TIA/dementia (hazard ratio 0.57 [CI 0.17, 1.97], p = 0.38) than those taking warfarin. Our community-based results suggest better long-term efficacy and safety of DOACs compared with warfarin. DOAC use was associated with a lower risk of cerebral ischemic events and new-onset dementia.

Four new direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the prevention of stroke in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation since 2010: dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban. Comparative advantages of DOACs include the absence of dietary interactions, fewer drug interactions, no need for routine monitoring of drug levels, equal to superior efficacy, and likely a decreased risk for bleeding, especially intracranial hemorrhage. These medications present an attractive alternative to Vitamin K antagonist (VKAs) for both patients and clinicians. Because DOACs have been in use, various guidelines have been updated recommending the use of DOACs or warfarin for the prevention of thromboembolism in patients with AF. We have found that multiple forms of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, are associated with atrial fibrillation. If DOACs consistently lower cerebral ischemic events and are associated with a significant reduction in intracranial hemorrhage, then a lower rate of dementia may be observed among patients taking a DOAC compared with warfarin. We and others have reported an association between quality of management of VKA therapy as measured by time in therapeutic range (TTR) and dementia. One hypothesis is that patients who have poor TTR are subject to both subtherapeutic and supratherapeutic anticoagulation, predisposing them to risk for microbleeds and microthromboemboli. Our primary aim is to report if the patient important outcomes of death, stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA), bleeding, major bleeding, and dementia differ between patients taking either a DOAC or warfarin managed as part of routine clinical care.

Methods

This study evaluated patients ≥18 years initiating long-term anticoagulation with warfarin or a DOAC from June 2010 to December 2014. Patients who received warfarin (target international normalized ratio [INR] 2 to 3) were managed by the Intermountain Healthcare Clinical Pharmacist Anticoagulation Service (CPAS). CPAS is a dedicated anticoagulation management service that uses a standardized algorithmic approach to make warfarin dose adjustments. Patients had to have at least 2 INR measurements under CPAS supervision to be included. Patients who received a DOAC were only included if they remained on the same DOAC initiated and continued this throughout follow-up.

Baseline characteristics were determined by International Classification of Diseases ( ICD ) -9 and ICD-10 codes. When evaluating the outcome of dementia, stroke, and TIA, patients with a history of dementia or any cognitive declines were excluded. Anticoagulant use before (pre) and any time after initiation of anticoagulation management by CPAS (post) was documented. INR measurements were obtained as per clinical algorithm and the discretion of the attending clinician.

Patients were followed for a median of 243 days for outcomes evaluated that included death, stroke/TIA, major bleed, bleed, and the composite outcome of dementia, stroke, and TIA. Stroke and TIA used ICD-9 and 10 codes (stroke: ICD-9 codes 433.1 and 434.1 and ICD-10 : I60.x, I61.x, I62.x, I63.x, I64.x; TIA: ICD-9 code 435.x). Major bleed was defined as a bleed in the brain or central nervous system, a gastrointestinal bleed, a genitourinary bleed, or a bleed requiring a blood transfusion that was nonsurgical. Bleed was defined as any other bleed not described earlier. Dementia (Alzheimer’s, vascular, senile, and nonspecified) used neurologist entered ICD-9 codes (290 to 294, 331). Death was determined by hospital records, Utah State Health Department records (death certificates), and through the Social Security death master index. Patients were censored at event occurrence (for the event being evaluated), death, or last known contact date. Patients not listed as deceased in any registry were considered to be alive.

The Student’s t test and the chi-square statistic were used to characterize the population. Continuous variables were described as means ± SD and discrete variables as frequencies. A propensity analysis was performed to minimize variance in confounding baseline characteristics. To estimate the propensity score, a logistic regression model was used in which anticoagulation use was regressed on the baseline characteristics. Patients were then matched 1:1 on propensity score (±0.01) and index date (6 ± months).

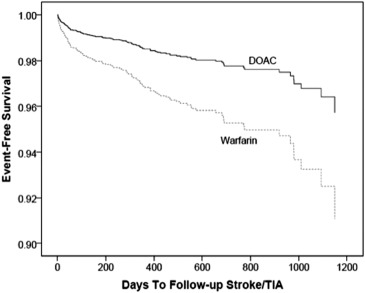

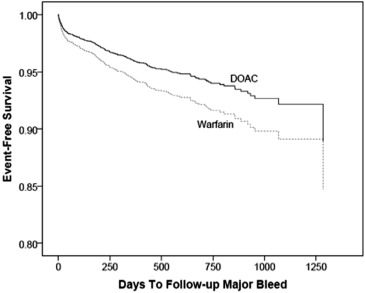

Multivariable Cox regression (SPSS, version 22.0) was performed to determine the risk of death, stroke/TIA, major bleed, bleed, and dementia by the anticoagulant therapy received. Final models retained only significant (p <0.05) and confounding (10% change in hazard ratio [HR]) covariables. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the log-rank test were used to estimate event-free survival among the outcomes. Two-tailed p values ≤0.05 were designated to be nominally significant.

All the baseline risk factors listed in Table 1 were evaluated in the multivariable models and pre-dated the end points.

| Characteristic | Warfarin | DOAC | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 73.5±9.6 | 71.2%±11.9 | <0.0001 |

| Men | 58.4% | 59.6% | 0.36 |

| Hypertension | 80.0% | 76.5% | 0.002 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 64.6% | 60.9% | 0.006 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 31.4% | 29.5% | 0.15 |

| Heart failure | 22.7% | 30.5% | <0.0001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 41.7% | 39.7% | 0.15 |

| Prior Percutaneous Coronary Intervention | 8.9% | 9.4% | 0.53 |

| Coronary bypass | 4.0% | 5.4% | 0.02 |

| Stroke/Transient Ischemic Attack | 10.7% | 10.8% | 0.89 |

| Macular degeneration | 1.8% | 1.7% | 0.75 |

| Prior bleed | 20.5% | 22.3% | 0.11 |

| Prior major bleed | 6.8% | 9.2% | 0.002 |

| History of vascular disease | 16.9% | 24.3% | <0.0001 |

| Prior thromboembolism | 0.1% | 7.2% | <0.0001 |

| Prior fall | 23.3% | 24.7% | 0.23 |

| Prior malignancy | 18.2% | 17.8% | 0.72 |

| CHADS 2 | <0.0001 | ||

| 0-1 | 31.2% | 37.8% | |

| 2-4 | 66.5% | 57.5% | |

| ≥5 | 2.3% | 4.7% | |

| CHADS 2 Vasc | <0.0001 | ||

| 0-1 | 4.0% | 16.1% | |

| 2-4 | 78.6% | 54.5% | |

| ≥5 | 17.4% | 29.4% |

Results

A total of 5,254 patients met inclusion criteria and were evaluated in this study. Table 1 lists the baseline characteristics of the study population. Average age was 72.4 ± 10.9 and 59.0% were men. Most patients were receiving long-term anticoagulation for AF management (warfarin: 96.5% vs DOAC: 92.7%, p <0.0001). In the warfarin group, only 2 patients underwent valve replacements. The average follow-up time in the warfarin group was 392.0 ± 342.3 days (median: 309) versus 292.0 ± 296.1 days (median: 185) in the DOAC group.

Patients taking DOAC comprised those taking rivaroxaban, n = 1,454 (55.3%), apixaban, n = 590 (22.5%), and dabigatran, n = 583 (22.2%). Baseline characteristics of previous stroke/TIA and previous bleeding did not differ between the groups (DOAC: 10.8% vs warfarin: 10.7, p = 0.89), yet more patients taking DOAC had a history of major bleeding (9.2% vs 6.8%, p = 0.002). CHA 2 DS 2 -VAS c scores were significantly (p <0.0001) different between the groups and are listed in Table 1 .

Major bleeding was observed more frequently among patients taking warfarin compared with those taking a DOAC (5.6% vs 4.3%, p = 0.03). Mortality was also higher in the warfarin group (10.1% warfarin vs 7.1% DOAC, p <0.0001). No difference in rates of major bleeding or death was observed comparing one DOAC with another.

Stroke/TIA occurred less frequently in patients taking a DOACs compared with those taking warfarin in the adjusted risk analysis (HR 0.47 [CI 0.32, 0.68], p <0.0001; Figure 1 ), and the risk of major bleeding was 0.70 ([CI 0.57, 0.85], p <0.0001; Figure 2 ). For the outcomes of death (HR 0.85 [CI 0.69, 1.03], p = 0.09, Figure 3 ) and bleeds (HR 0.87[CI 0.72, 1.04], p = 0.14), no difference was observed.