A man admitted for deep vein thrombosis of his leg is found to have an important unrelated electrocardiographic abnormality. In the second paragraph, either reinsert the comma after V1 in the fifth line or remove the comma after enlargement in the fourth line.

A 45-year-old man was admitted to the hospital after he woke up that morning with severe left calf swelling and pain. Examination revealed left calf tenderness, swelling, and warmth. Ultrasonic images demonstrated deep venous thrombosis in the left leg.

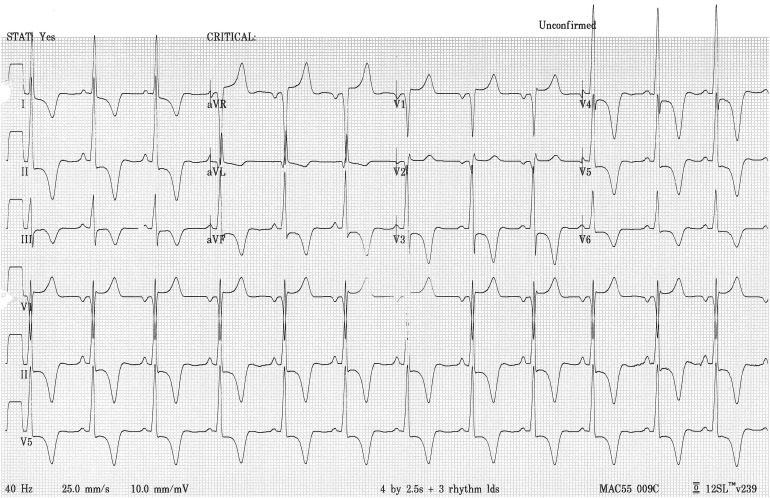

The patient denied trauma to the left leg, dyspnea, and chest discomfort. Cardiovascular physical examination was normal except for the left leg and blood pressure readings of 130/76 to 181/91 mm Hg. An electrocardiogram was positive for left atrial enlargement, manifested by large terminal P-wave deflections in lead V 1 and for both limb and precordial lead voltage criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy. Furthermore, striking ST-segment depression and T-wave inversion in the lateral and inferior leads, accompanied by reciprocal ST-segment elevation and upright T waves in lead aVR and the anterior precordial leads, the so-called strain pattern, were even more ominous signs of left ventricular hypertrophy ( Figure 1 ). An echocardiogram confirmed left ventricular hypertrophy, and left ventricular systolic function was normal. The left ventricular myocardium was diffusely hypertrophied and appeared thicker than usual at the apex.

Manual laborers may be prone to deep vein thrombosis of the legs because of work-related trauma. Although this patient did not recall trauma to the left leg, he had earlier undergone upper extremity orthopedic procedures because of trauma occurring at work. The left leg venous thrombosis was treated with subcutaneous fondaparinux sodium followed by oral warfarin sodium, and his recovery was uneventful. His electrocardiogram remained unchanged during hospitalization and follow-up.

Striking repolarization changes of left ventricular hypertrophy, such as those shown in the Figure 1 , with negative T-wave voltage ≥1.0 mV, have been described in apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which seems especially prevalent in Japan. Similar striking negative T-waves, however, can be seen in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy without unusual apical thickening, in valvular aortic stenosis, long-standing severe aortic regurgitation, systemic arterial hypertension, and subendocardial ischemia or injury. The presence of repolarization changes in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy has long been known to worsen prognosis, and in a recent study by Jindal et al, the left ventricular strain pattern had the highest hazard ratio for cardiovascular death of any of the electrocardiographic components of each of 2 modifications of the Romhilt-Estes score for left ventricular hypertrophy.

It has now been 3 years since our patient was seen for deep vein thrombosis. In general, he is doing well and works regularly. Blood pressure readings on emergency room visits for dysuria and leg cramps have been 188/93 and 159/101 mm Hg, respectively, and he is currently on no antihypertensive medications. Is his left ventricular hypertrophy more than one would expect for this hemodynamic burden, the criterion for diagnosing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy? The point is arguable, but academic. The man needs his blood pressure lowered.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

See page 1790 for disclosure information.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree