Intraoperative Echocardiography

Roger L. Click

Jae K. Oh

Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography (IOTEE) has become a routine addition to most cardiac operations (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10). Echocardiography was introduced into the cardiac operating room in 1972 with epicardial scanning (11). Although epicardial scanning is still used in a few specific situations (12), IOTEE has become the more commonly used method for visualizing cardiac structures in the operating room.

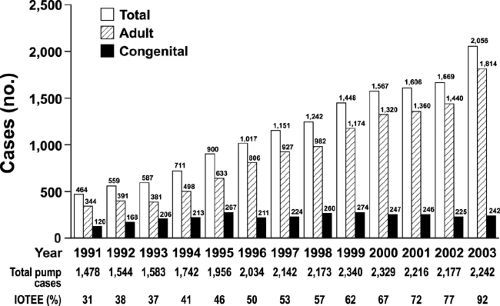

The Mayo Clinic experience with IOTEE over the past 13 years is summarized in Figure 21-1. The surgical volume increased steadily during these years, and more surgeons are using IOTEE for more operations. Initially, IOTEE was used in about one-third of all cardiac operations; currently, it is performed in more than 90% of all cardiac operations.

Iotee Application

Reasons for performing IOTEE are the following: 1) prebypass—to confirm the preoperative findings and the reason for the operation and to screen for any new findings that may alter the surgical plan, 2) postbypass—to check the surgical result and to screen for any new abnormalities that may require further intervention or return to cardiopulmonary bypass, 3) to minimize cardiovascular complications during cardiac and noncardiac operations by monitoring left ventricular (LV) function and wall motion, and 4) to identify any cardiovascular factors that may be responsible in patients who become hemodynamically unstable in the operating room.

IOTEE involves multiple disciplines and requires cooperation among anesthesiologists, cardiologists, and surgeons. Because the anesthesiologist is in charge of the patient’s hemodynamic condition and airway, the transesophageal probe is usually inserted by the anesthesiologist. If he or she is comfortable with performing transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), baseline TEE data can be obtained and reviewed in conjunction with a cardiologist-echocardiographer. The anesthesiologist routinely monitors for air in the cardiac chambers or regional wall motion abnormalities. In cases of valve or congenital heart surgery at Mayo Clinic, the cardiologist-echocardiographer usually is actively involved from the beginning of the operation.

Implementation

Routine TEE is performed prebypass in all patients. Further attention is then focused on the specific surgical referral. Prebypass TEE findings are then discussed with the cardiac surgeon and anesthesiologist. Any new findings are reviewed with the surgeon to determine if the surgical plan needs to be altered. After the patient comes off the bypass pump, IOTEE is repeated to assess the results of the operation. The postbypass echocardiographic findings are discussed with the surgeon. When the structural or hemodynamic results are considered inadequate, a second pump run may be initiated to revise the operation, after which the results are again evaluated with echocardiography. However, it is not realistic to attempt perfect repair in all surgical cases. If a hemodynamically insignificant lesion remains, it is better to leave it than to return and revise the repair. Occasionally, it is difficult to determine the long-term outcome of mild abnormalities shown on IOTEE that are not immediately causing hemodynamic abnormalities. Therefore, postbypass, it is important to

wait until after the hemodynamics have stabilized and are optimal before making final decisions on the basis of IOTEE.

wait until after the hemodynamics have stabilized and are optimal before making final decisions on the basis of IOTEE.

Indications

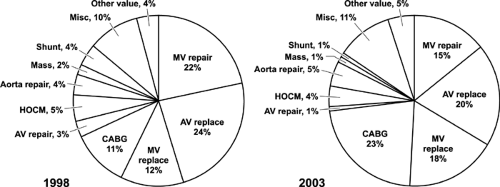

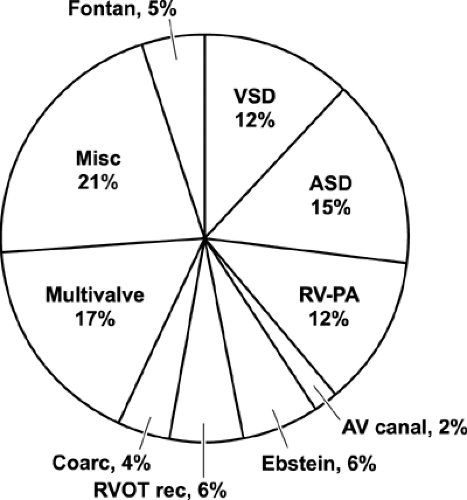

The case distribution for adult and congenital cases is shown in Figures 21-2 and 21-3, respectively. Initially, in our experience, the adult distribution of surgical cases having IOTEE was very similar each year, with predominantly valve surgery, that is, with repair and replacement, accounting for more than half of the adult cases in which IOTEE was used (Fig. 21-2). In contrast, in the past 3 years, the use of IOTEE has increased for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, up from 11% of all adult cases in 1998 to 23% of all cases in 2003 (Fig. 21-2). This increased use of IOTEE in CABG surgery results from the surgeon’s comfort with IOTEE and firsthand knowledge of the impact of IOTEE in even routine cardiac surgical cases (13).

Currently at Mayo Clinic, IOTEE is requested for nearly all adult patients undergoing the following cardiovascular procedures: all valve repairs, suspicion of clinically significant mitral valve regurgitation in patients having aortic valve replacement, aorta repair for dissection or aneurysm, myectomy procedure for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM), repair of an intracardiac shunt, removal of an intracardiac mass, all congenital cases,

and in most patients having routine valve replacement or CABG.

and in most patients having routine valve replacement or CABG.

Practical guidelines for performing IOTEE were published in 1999 (14). Indications for IOTEE were divided in three categories, depending on evidence at the time for the impact of IOTEE on a given surgical procedure. Since then, numerous articles have supported the use of IOTEE in almost all types of cardiac surgery (15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26).

IOTEE has been used in all congenital surgical cases at Mayo Clinic since pediatric probes became available. The number of congenital cases has remained constant (Fig. 21-1). The distribution of types of congenital cases is shown in Figure 21-3, and it also has been constant.

Impact of Iotee

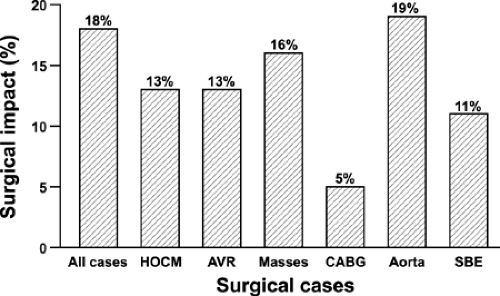

At Mayo Clinic and other institutions, the impact of IOTEE has been evaluated (1,3). We have analyzed and continue to prospectively analyze our IOTEE practice in regard to its usefulness for the surgical practice and, in particular, alterations of the surgical practice or decisions in the operating room based on IOTEE. In 2000, we published our first 5-year experience with more than 3,000 adult cases (1). Prebypass, new findings were found in 15% of patients, altering surgery in 14%; postbypass, new information was found in 6%, altering surgery or management in 4%. The overall impact was 18% (Fig. 21-4). Figure 21-4 shows the overall impact of IOTEE on surgery in all cases and in HOCM, aorta valve surgery, mass removal, CABG, aortic surgery, and valve surgery for endocarditis. Even for patients having only CABG, the overall impact was 5%. The impact of IOTEE prebypass is illustrated in Figures 21-5, 21-6 and 21-7 and the postbypass impact, in Figures 21-8 and 21-9.

Cost analysis has also shown IOTEE to be a valued adjunct to cardiovascular surgery (27). In our own analysis, if one considers the cost of IOTEE versus the cost of a redo operation to correct something missed, only two or three cases per 100 need have an impact to offset the IOTEE cost. This does not account for the increased risk to the patient for a redo operation.

Occasionally, IOTEE may miss something. Most commonly, this involves a valve lesion, such as perforations

or the number of broken chordae tendinae, and has little impact on the final surgical decision (28) (Fig. 21-10).

or the number of broken chordae tendinae, and has little impact on the final surgical decision (28) (Fig. 21-10).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree