INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

The prototypic lesion of infective endocarditis, the vegetation (Fig. 25-1), is a mass of platelets, fibrin, microcolonies of microorganisms, and scant inflammatory cells. Infection most commonly involves heart valves (either native or prosthetic) but may also occur on the low-pressure side of a ventricular septal defect, on the mural endocardium where it is damaged by aberrant jets of blood or foreign bodies, or on intracardiac devices themselves. The analogous process involving arteriovenous shunts, arterioarterial shunts (patent ductus arteriosus), or a coarctation of the aorta is called infective endarteritis.

FIGURE 25-1

Vegetations (arrows) due to viridans streptococcal endocarditis involving the mitral valve.

Endocarditis may be classified according to the temporal evolution of disease, the site of infection, the cause of infection, or a predisposing risk factor such as injection drug use. While each classification criterion provides therapeutic and prognostic insight, none is sufficient alone. Acute endocarditis is a hectically febrile illness that rapidly damages cardiac structures, hematogenously seeds extracardiac sites, and, if untreated, progresses to death within weeks. Subacute endocarditis follows an indolent course; causes structural cardiac damage only slowly, if at all; rarely metastasizes; and is gradually progressive unless complicated by a major embolic event or ruptured mycotic aneurysm.

In developed countries, the incidence of endocarditis ranges from 2.6 to 7 cases per 100,000 population per year and has remained relatively stable during recent decades. While congenital heart diseases remain a constant predisposition, predisposing conditions in developed countries have shifted from chronic rheumatic heart disease (which remains a common predisposition in developing countries) to illicit IV drug use, degenerative valve disease, and intracardiac devices. The incidence of endocarditis is notably increased among the elderly. In developed countries, 30–35% of cases of native valve endocarditis (NVE) are associated with health care, and 16–30% of all cases of endocarditis involve prosthetic valves. The risk of prosthesis infection is greatest during the first 6–12 months after valve replacement; gradually declines to a low, stable rate thereafter; and is similar for mechanical and bioprosthetic devices.

In developed countries, the incidence of endocarditis ranges from 2.6 to 7 cases per 100,000 population per year and has remained relatively stable during recent decades. While congenital heart diseases remain a constant predisposition, predisposing conditions in developed countries have shifted from chronic rheumatic heart disease (which remains a common predisposition in developing countries) to illicit IV drug use, degenerative valve disease, and intracardiac devices. The incidence of endocarditis is notably increased among the elderly. In developed countries, 30–35% of cases of native valve endocarditis (NVE) are associated with health care, and 16–30% of all cases of endocarditis involve prosthetic valves. The risk of prosthesis infection is greatest during the first 6–12 months after valve replacement; gradually declines to a low, stable rate thereafter; and is similar for mechanical and bioprosthetic devices.

ETIOLOGY

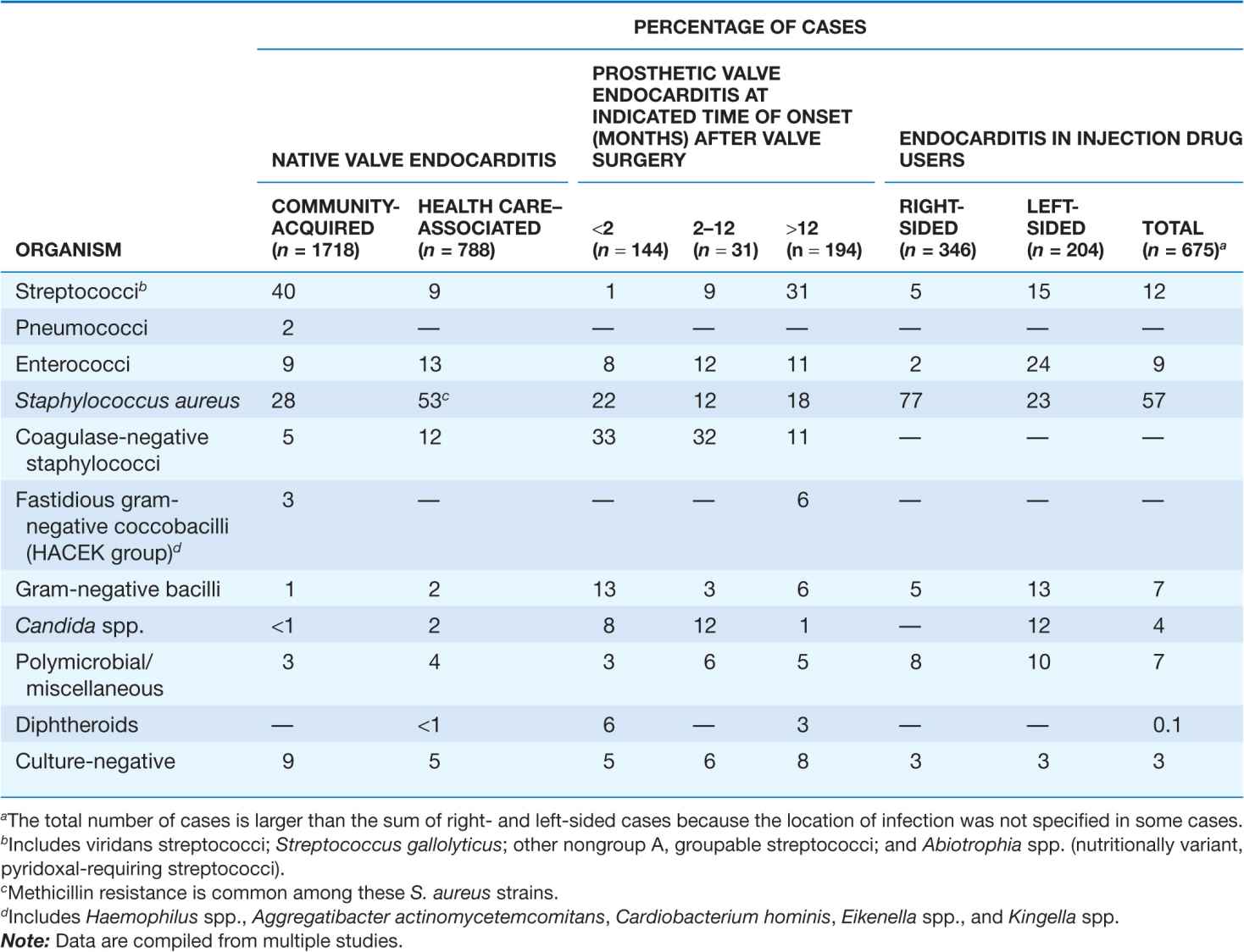

Although many species of bacteria and fungi cause sporadic episodes of endocarditis, a few bacterial species cause the majority of cases (Table 25-1). Because of their different portals of entry, the pathogens involved vary somewhat with the clinical types of endocarditis. The oral cavity, skin, and upper respiratory tract are the respective primary portals for the viridans streptococci, staphylococci, and HACEK organisms (Haemophilus, Actinobacillus, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, and Kingella; Haemophilus aphrophilus and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans have been reclassified into the genus Aggregatibacter). Streptococcus gallolyticus (formerly S. bovis) originates from the gastrointestinal tract, where it is associated with polyps and colonic tumors, and enterococci enter the bloodstream from the genitourinary tract. Health care–associated NVE, commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), and enterococci, has a nosocomial onset (55%) or a community onset (45%) in patients who have had extensive contact with the health care system over the preceding 90 days. Endocarditis complicates 6–25% of episodes of catheter-associated S. aureus bacteremia; the higher rates are detected by careful transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) screening (see “Echocardiography,” later).

TABLE 25-1

ORGANISMS CAUSING MAJOR CLINICAL FORMS OF ENDOCARDITIS

Prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) arising within 2 months of valve surgery is generally nosocomial, the result of intraoperative contamination of the prosthesis or a bacteremic postoperative complication. This nosocomial origin is reflected in the primary microbial causes: S. aureus, CoNS, facultative gram-negative bacilli, diphtheroids, and fungi. The portals of entry and organisms causing cases beginning >12 months after surgery are similar to those in community-acquired NVE. PVE due to CoNS that presents 2–12 months after surgery often represents delayed-onset nosocomial infection. Regardless of the time of onset after surgery, at least 68–85% of CoNS strains that cause PVE are resistant to methicillin.

Transvenous pacemaker– or implanted defibrillator– associated endocarditis is usually nosocomial. The majority of episodes occur within weeks of implantation or generator change and are caused by S. aureus or CoNS, both of which are commonly resistant to methicillin.

Endocarditis occurring among injection drug users, especially that involving the tricuspid valve, is commonly caused by S. aureus, many strains of which are resistant to methicillin. Left-sided valve infections in addicts have a more varied etiology. In addition to the usual causes of endocarditis, these cases are caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida species and sporadically by unusual organisms such as Bacillus, Lactobacillus, and Corynebacterium species. Polymicrobial endocarditis occurs among injection drug users. HIV infection in drug users does not significantly influence the causes of endocarditis.

From 5% to 15% of patients with endocarditis have negative blood cultures; in one-third to one-half of these cases, cultures are negative because of prior antibiotic exposure. The remainder of these patients are infected by fastidious organisms, such as nutritionally variant organisms (now designated Granulicatella and Abiotrophia species), HACEK organisms, Coxiella burnetii, and Bartonella species. Some fastidious organisms occur in characteristic geographic settings (e.g., C. burnetii and Bartonella species in Europe, Brucella species in the Middle East). Tropheryma whipplei causes an indolent, culture-negative, afebrile form of endocarditis.

PATHOGENESIS

The endothelium, unless damaged, is resistant to infection by most bacteria and to thrombus formation. Endothelial injury (e.g., at the site of impact of high-velocity blood jets or on the low-pressure side of a cardiac structural lesion) allows either direct infection by virulent organisms or the development of an uninfected platelet-fibrin thrombus—a condition called nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE). The thrombus subsequently serves as a site of bacterial attachment during transient bacteremia. The cardiac conditions most commonly resulting in NBTE are mitral regurgitation, aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation, ventricular septal defects, and complex congenital heart disease. NBTE also arises as a result of a hypercoagulable state; this phenomenon gives rise to the clinical entity of marantic endocarditis (uninfected vegetations seen in patients with malignancy and chronic diseases) and to bland vegetations complicating systemic lupus erythematosus and the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

Organisms that cause endocarditis generally enter the bloodstream from mucosal surfaces, the skin, or sites of focal infection. Except for more virulent bacteria (e.g., S. aureus) that can adhere directly to intact endothelium or exposed subendothelial tissue, microorganisms in the blood adhere at sites of NBTE. If resistant to the bactericidal activity of serum and the microbicidal peptides released locally by platelets, the organisms proliferate and induce platelet deposition and a procoagulant state at the site by eliciting tissue factor from the endothelium or, in the case of S. aureus, from monocytes as well. Fibrin deposition combines with platelet aggregation and microorganism proliferation to generate an infected vegetation. The organisms that commonly cause endocarditis have surface adhesin molecules, collectively called microbial surface components recognizing adhesin matrix molecules (MSCRAMMs), that mediate adherence to NBTE sites or injured endothelium. Fibronectin-binding proteins present on many gram-positive bacteria, clumping factor (a fibrinogen- and fibrin-binding surface protein) on S. aureus, and glucans or FimA (a member of the family of oral mucosal adhesins) on streptococci facilitate adherence. Fibronectin-binding proteins are required for S. aureus invasion of intact endothelium; thus these surface proteins may facilitate infection of previously normal valves. In the absence of host defenses, organisms enmeshed in the growing platelet-fibrin vegetation proliferate to form dense microcolonies. Organisms deep in vegetations are metabolically inactive (nongrowing) and relatively resistant to killing by antimicrobial agents. Proliferating surface organisms are shed into the bloodstream continuously.

The pathophysiologic consequences and clinical manifestations of endocarditis—other than constitutional symptoms, which probably result from cytokine production—arise from damage to intracardiac structures; embolization of vegetation fragments, leading to infection or infarction of remote tissues; hematogenous infection of sites during bacteremia; and tissue injury due to the deposition of circulating immune complexes or immune responses to deposited bacterial antigens.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

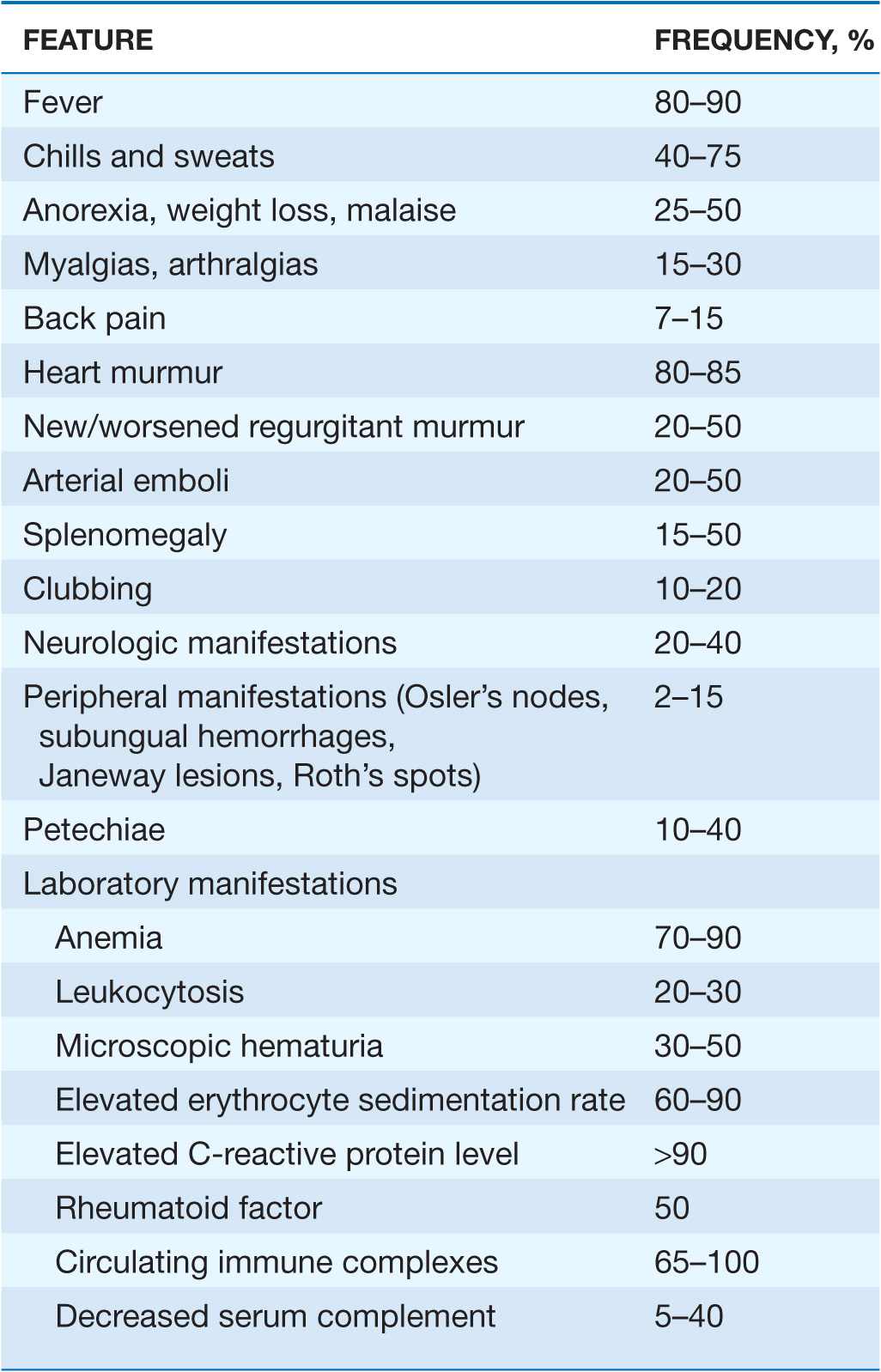

The clinical syndrome of infective endocarditis is highly variable and spans a continuum between acute and sub-acute presentations. NVE (whether acquired in the community or in association with health care), PVE, and endocarditis due to injection drug use share clinical and laboratory manifestations (Table 25-2). The causative microorganism is primarily responsible for the temporal course of endocarditis. β-Hemolytic streptococci, S. aureus, and pneumococci typically result in an acute course, although S. aureus occasionally causes subacute disease. Endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus lugdunensis (a coagulase-negative species) or by enterococci may present acutely. Subacute endocarditis is typically caused by viridans streptococci, enterococci, CoNS, and the HACEK group. Endocarditis caused by Bartonella species, T. whipplei, or C. burnetii is exceptionally indolent.

TABLE 25-2

CLINICAL AND LABORATORY FEATURES OF INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

The clinical features of endocarditis are nonspecific. However, these symptoms in a febrile patient with valvular abnormalities or a behavior pattern that predisposes to endocarditis (e.g., injection drug use) suggest the diagnosis, as do bacteremia with organisms that frequently cause endocarditis, otherwise-unexplained arterial emboli, and progressive cardiac valvular incompetence. In patients with subacute presentations, fever is typically low grade and rarely exceeds 39.4°C (103°F); in contrast, temperatures of 39.4°–40°C (103°–104°F) are often noted in acute endocarditis. Fever may be blunted or absent in patients who are elderly or severely debilitated or who have marked cardiac or renal failure.

Cardiac manifestations

Although heart murmurs are usually indicative of the predisposing cardiac pathology rather than of endocarditis, valvular damage and ruptured chordae may result in new regurgitant murmurs. In acute endocarditis involving a normal valve, murmurs may be absent initially but ultimately are detected in 85% of cases. Congestive heart failure (CHF) develops in 30–40% of patients; it is usually a consequence of valvular dysfunction but occasionally is due to endocarditis-associated myocarditis or an intracardiac fistula. Heart failure due to aortic valve dysfunction progresses more rapidly than does that due to mitral valve dysfunction. Extension of infection beyond valve leaflets into adjacent annular or myocardial tissue results in perivalvular abscesses, which in turn may cause intracardiac fistulae with new murmurs. Abscesses may burrow from the aortic valve annulus through the epicardium, causing pericarditis, or into the upper ventricular septum, where they may interrupt the conduction system, leading to varying degrees of heart block. Perivalvular abscesses arising from the mitral valve rarely interrupt conduction pathways near the atrioventricular node or in the proximal bundle of His. Emboli to a coronary artery occur in 2% of patients and may result in myocardial infarction.

Noncardiac manifestations

The classic nonsuppurative peripheral manifestations of subacute endocarditis are related to the duration of infection and, with early diagnosis and treatment, have become infrequent. In contrast, septic embolization mimicking some of these lesions (subungual hemorrhage, Osler’s nodes) is common in patients with acute S. aureus endocarditis (Fig. 25-2). Musculoskeletal pain usually remits promptly with treatment but must be distinguished from focal metastatic infections (e.g., spondylodiscitis), which may complicate 10–15% of cases. Hematogenously seeded focal infection is most often clinically evident in the skin, spleen, kidneys, skeletal system, and meninges. Arterial emboli are clinically apparent in up to 50% of patients. Endocarditis caused by S. aureus, vegetations >10 mm in diameter (as measured by echocardiography), and infection involving the mitral valve are independently associated with an increased risk of embolization. Emboli occurring late, during, or after effective therapy do not in themselves constitute evidence of failed antimicrobial treatment. Cerebrovascular emboli presenting as strokes or occasionally as encephalopathy complicate 15–35% of cases of endocarditis. One-half of these events precede the diagnosis of endocarditis. The frequency of stroke is 8 per 1000 patient-days during the week prior to diagnosis; the figure falls to 4.8 and 1.7 per 1000 patient-days during the first and second weeks of effective antimicrobial therapy, respectively. This decline exceeds that which can be attributed to change in vegetation size. Only 3% of strokes occur after 1 week of effective therapy. Other neurologic complications include aseptic or purulent meningitis, intracranial hemorrhage due to hemorrhagic infarcts or ruptured mycotic aneurysms, and seizures. (Mycotic aneurysms are focal dilations of arteries occurring at points in the artery wall that have been weakened by infection in the vasa vasorum or where septic emboli have lodged.) Microabscesses in brain and meninges occur commonly in S. aureus endocarditis; surgically drainable intracerebral abscesses are infrequent.

FIGURE 25-2

Septic emboli with hemorrhage and infarction due to acute Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. (Used with permission of L. Baden.)

Immune complex deposition on the glomerular basement membrane causes diffuse hypocomplementemic glomerulonephritis and renal dysfunction, which typically improve with effective antimicrobial therapy. Embolic renal infarcts cause flank pain and hematuria but rarely cause renal dysfunction.

Manifestations of specific predisposing conditions

Almost 50% of endocarditis cases associated with injection drug use are limited to the tricuspid valve and present with fever but with faint or no murmur. In 75% of cases, septic emboli cause cough, pleuritic chest pain, nodular pulmonary infiltrates, or occasionally pyopneumothorax. Infection of the aortic or mitral valves on the left side of the heart presents with the typical clinical features of endocarditis.

Health care–associated endocarditis has typical manifestations if it is not associated with a retained intracardiac device or masked by the symptoms of concurrent comorbid illness. Transvenous pacemaker– or implanted defibrillator–associated endocarditis may be associated with obvious or cryptic generator pocket infection and results in fever, minimal murmur, and pulmonary symptoms due to septic emboli.

Late-onset PVE presents with typical clinical features. In cases arising within 60 days of valve surgery (early onset), typical symptoms may be obscured by comorbidity associated with recent surgery. In both early-onset and more delayed presentations, paravalvular infection is common and often results in partial valve dehiscence, regurgitant murmurs, CHF, or disruption of the conduction system.

DIAGNOSIS

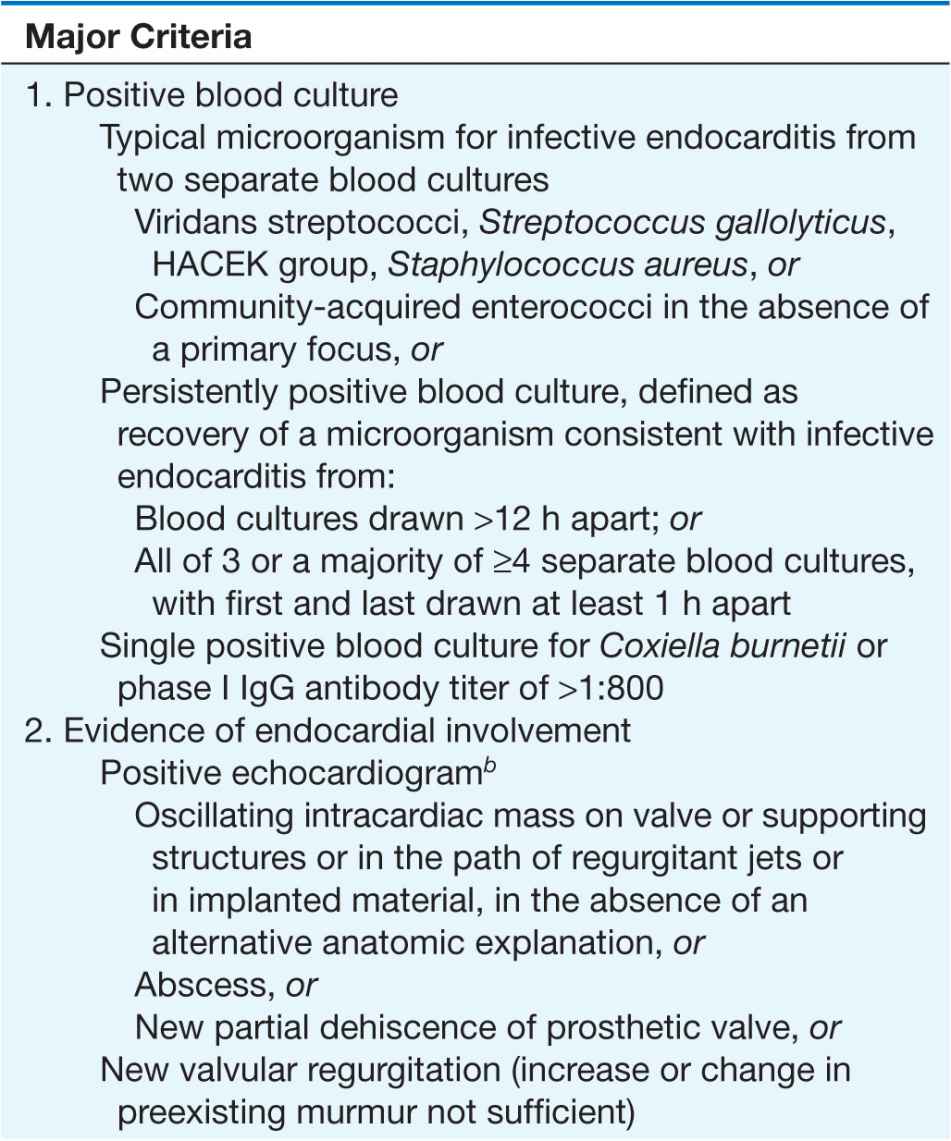

The Duke criteria

The diagnosis of infective endocarditis is established with certainty only when vegetations are examined histologically and microbiologically. Nevertheless, a highly sensitive and specific diagnostic schema—known as the Duke criteria—has been developed on the basis of clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic findings (Table 25-3). Documentation of two major criteria, of one major criterion and three minor criteria, or of five minor criteria allows a clinical diagnosis of definite endocarditis. The diagnosis of endocarditis is rejected if an alternative diagnosis is established, if symptoms resolve and do not recur with ≤4 days of antibiotic therapy, or if surgery or autopsy after ≤4 days of antimicrobial therapy yields no histologic evidence of endocarditis. Illnesses not classified as definite endocarditis or rejected as such are considered cases of possible infective endocarditis when either one major criterion and one minor criterion or three minor criteria are fulfilled. Requiring the identification of clinical features of endocarditis for classification as possible infective endocarditis increases the specificity of the schema without significantly reducing its sensitivity.

TABLE 25-3

THE DUKE CRITERIA FOR THE CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS OF INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITISa

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree