Infective Endocarditis

Infective endocarditis occurs primarily on cardiac valves, but it also can involve other endocardial surfaces or intracardiac devices. It is potentially fatal, with a 6-month mortality rate of 25% to 35%. The rate of cure with penicillin in the 1950s was 70%, and this rate has not improved significantly since then because of more antibiotic-resistant organisms, prothesis- or device-related endocarditis, and more patients with major comorbid conditions (1). The incidence is higher among patients who have valvular heart disease (rheumatic valve, bicuspid aortic valve, mitral valve prolapse, or prosthetic valve) or congenital heart disease and among intravenous drug users. The hydraulic features of the blood stream are important in the pathogenesis of endocarditis. Endocarditis is associated with a high-pressure source (i.e., aorta, left ventricle) that drives blood at a high velocity through a narrow orifice (coarctation, ductus arteriosus, ventricular septal defect, regurgitant aortic or mitral valve, or obstructive hypertrophic cardiac myopathy) into a low-pressure chamber (2). Most commonly, the mitral and aortic valves are involved by endocarditis, but involvement of valves of the right side of the heart is not uncommon, especially in intravenous drug users. Because the consequence of untreated endocarditis is devastating and often fatal, it is of utmost importance that the underlying infection and its complications be recognized promptly and treated appropriately.

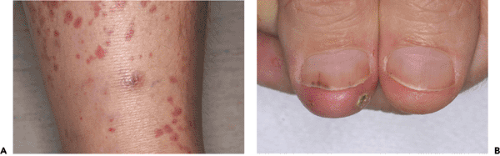

Although a patient with infective endocarditis may have characteristic clinical symptoms and signs (Fig. 14-1), they are not always present. Furthermore, the diagnosis of endocarditis requires objective laboratory data.

Since the first M-mode echocardiographic observation of valvular vegetation in 1973 (3), the role of echocardiography in diagnosing infective endocarditis has grown in conjunction with improvements in resolution and technology, including Doppler echocardiography, color flow imaging, and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). Currently, echocardiography is the diagnostic procedure of choice for detecting valvular vegetation. Indeed, the echocardiographic detection of vegetation is one of the two major diagnostic criteria for infective endocarditis. A patient with endocarditis may have negative findings on blood culture if the infection is partially treated or caused by an esoteric or fastidious organism. Therefore, the diagnosis of infective endocarditis may be suggested by echocardiographic findings even if the blood culture results are negative (or before positive results are reported).

New Diagnostic Criteria

Since 1981, the diagnosis of endocarditis has been based on the criterion of Von Reyn and colleagues (4): definite diagnosis of infective endocarditis was possible only from direct histologic examination of the involved tissue or positive findings on bacteriologic studies. Therefore, even in patients who showed the symptoms and signs typical of the acute stage of infection, the diagnosis of infective endocarditis could not be made without positive blood culture results. At the time the Von Reyn criterion was established, the diagnostic capability of echocardiography was not fully developed. With further advances in echocardiography, including TEE, that improved the detection of vegetation, abscesses, and other complications of endocarditis, echocardiography now provides major diagnostic information. Certain characteristics of valvular masses seen with echocardiography are sometimes as diagnostic as the detection of typical organisms in blood culture, such as HACEK (Haemophilus spp., Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella spp., and Kingella kingae) (Table 14-1).

To improve the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic criteria for infective endocarditis, new major and minor criteria (Duke criteria) have been proposed (5). The two major and six minor criteria are listed in Table 14-1. The diagnosis of infective endocarditis is definite if a patient meets two major criteria, or one major criterion plus three

minor criteria, or five minor criteria (Table 14-2). Echocardiographic evidence typical of endocarditis is one of the major criteria, and it can be used to diagnose infective endocarditis definitely in combination with three minor criteria, even without typical positive blood culture results. The new Duke criteria were compared with the Von Reyn criterion by Bayer and colleagues (6) in 63 febrile patients who had suspected infective endocarditis. More cases were classified as “definite” with the Duke criteria, and the detection of vegetation with echocardiography was important in making the diagnosis of endocarditis in 57% of patients.

minor criteria, or five minor criteria (Table 14-2). Echocardiographic evidence typical of endocarditis is one of the major criteria, and it can be used to diagnose infective endocarditis definitely in combination with three minor criteria, even without typical positive blood culture results. The new Duke criteria were compared with the Von Reyn criterion by Bayer and colleagues (6) in 63 febrile patients who had suspected infective endocarditis. More cases were classified as “definite” with the Duke criteria, and the detection of vegetation with echocardiography was important in making the diagnosis of endocarditis in 57% of patients.

Table 14-1 Definition of terms used in the proposed diagnostic criteria | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Table 14-2 New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis | |

|---|---|

|

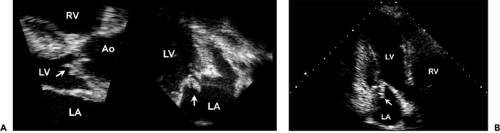

Echocardiographic Appearance

The echocardiographic features typical of infective endocarditis are 1) an oscillating intracardiac mass on a valve or supporting structure or in the path of a regurgitation jet or on an iatrogenic device, 2) abscesses, 3) new partial dehiscence of a prosthetic valve, or 4) new valvular regurgitation. The initial attachment site to the mitral and tricuspid valves is usually on the atrial side, but an aortic vegetation usually starts from the ventricular surface (Fig. 14-2). A vegetation appears as an echogenic (mobile) mass or masses attached to the valve, endocardial surface, or prosthetic materials in the heart (Fig. 14-3, 14-4 and 14-5). Vegetations can be linear, round, irregular, or shaggy, and they frequently show high-frequency flutter or oscillations (7). The sensitivity of two-dimensional echocardiography for the detection of vegetation depends on the size and location of the vegetation and the echocardiographic window used. The sensitivity of detecting a vegetation with two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is 65% to 80% and with TEE, 95% (8,9,10,11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree