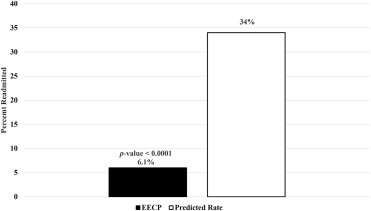

Heart failure (HF) affects millions of Americans and causes financial burdens because of the need for rehospitalization. For this reason, health care systems and patients alike are seeking methods to decrease readmissions. We assessed the potential for reducing readmissions of patients with postacute care HF through an educational program combined with enhanced external counterpulsation (EECP). We examined 99 patients with HF who were referred to EECP centers and received heart failure education and EECP treatment within 90 days of hospital discharge from March 2013 to January 2015. We compared observed and predicted 90-day readmission rates and examined results of 6-minute walk tests, Duke Activity Status Index, New York Heart Association classification, and Canadian Cardiovascular Society classification before and after EECP. Patients were treated with EECP at a median augmentation pressure of 280 mm Hg (quartile 1 = 240, quartile 3 = 280), achieved as early as the first treatment. Augmentation ratios varied from 0.4 to 1.9, with a median of 1.0 (quartile 1 = 0.8, quartile 3 = 1.2). Only 6 patients (6.1%) had unplanned readmissions compared to the predicted 34%, p <0.0001. The average increase in distance walked was 52 m (18.4%), and the median increase in Duke Activity Status Index was 9.95 points (100%), p values <0.0001. New York Heart Association and Canadian Cardiovascular Society classes improved in 61% and 60% of the patients, respectively. In conclusion, patients with HF who received education and EECP within 90 days of discharge had significantly lower readmission rates than predicted, and improved functional status, walk distance, and symptoms.

In March 1995, the US Food and Drug Administration granted 510(k) clearance to market enhanced external counterpulsation (EECP) for the treatment of angina pectoris, acute myocardial infarction, and cardiogenic shock. Clinical indications expanded in 2002 to include heart failure (HF). An EECP characteristic of particular relevance to the population with HF is the systolic unloading of the left ventricle during deflation, resulting in reduced afterload and improved ejection fraction. HF affects roughly 5.7 million Americans, causes over 1,000,000 hospitalizations each year, and was estimated to cost 32.4 billion dollars in 2015, with millions of dollars attributed to 30-day readmission penalties. Thus, health care systems and patients alike are seeking innovative methods to decrease readmissions. In 2007, Soran et al. observed an 83% posttreatment reduction of hospitalization for ischemic patients with low ejection fraction. In other studies, EECP improved quality of life, increased exercise tolerance and peak volume of oxygen consumption, and improved New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification. As attention centers on HF readmission as a target of clinical effectiveness, the role of tailored EECP programs coupled with education regarding medication and diet is worthy of examination and is the purpose of this report.

Methods

Legacy (Trinity) Heart Care provided EECP treatment using Vasomedical Inc. equipment at standalone facilities in multiple US metropolitan areas to patients referred from hospitals and practitioners for EECP therapy. After receiving patients’ informed consent and institutional review board’s approval, the program tracked patients with HF due to ischemic cardiomyopathy who were referred for treatment after hospitalization from 65 physicians. These patients were referred from March 2013 through January 2015 during hospital stays or acute phase after discharge if they had HF, angina, or angina equivalent and were not amenable for further revascularization. The established protocols of the program were consistently administered to the patients. Once a patient was referred, the regional center made contact through telephone within approximately 24 hours. This initial contact lasted roughly 20 minutes and outlined the program, shared details on why the patient was referred, and scheduled the first visit. A patient’s first visit to the clinic was a 90-minute orientation, including program education, treatment exposure, and an extended session with the nurse practitioner or physician assistant to discuss the patient’s condition and treatment goals. Additionally, patients had a physical examination, discussed their initial disease state, and scheduled their treatment. Patients typically began treatment within 2 weeks of referral and had multiple discussions with clinical staff before the first EECP session.

Our interest was in patients who were referred and began EECP within 90 days after discharge. To qualify for EECP treatment, patients were required to be on a maximally tolerated medical treatment; compliance with this requirement was documented through medical records obtained from the referring physician or hospital records. Additionally, patients were prescribed either a long-acting nitrate or had access to short-acting nitrates as needed. All patients were diagnosed with HF, actively experiencing angina or angina equivalents, and were referred after hospitalization. Treatment consisted of 35 1-hour EECP sessions, delivered 5 days/week over 7 weeks. During each session, the patients experienced a rapid treatment pressure increase. Within 5 minutes, patients were at a high-level minimum therapeutic pressure, which reduced the risk of fluid overload. Patients had daily clinical contact, including counsel on weight (measured daily), symptom tracking, dietary education, vital signs assessment before and after treatment, monitoring of the electrocardiogram, and medication management follow-up. This was part of a broader chronic care management effort delivered by experienced midlevel cardiac providers. During the 7-week regimen, there was a tight, multidiscipline provider feedback loop. The EECP midlevel provider enabled crossdiscipline communication regarding compliance and symptom and disease progression. The combination of education, communication, and EECP therapy was the focus in attempting to reduce hospital readmissions. After treatment, the protocol also included ongoing patient engagement and tracking, through a face-to-face survey between patient and clinical team. These interactions took place at 30 days, 60 days, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after treatment.

There were 99 patients across 5 participating centers who met criteria for this study (i.e., they were referred and began EECP treatment within 90 days of hospital discharge). The data for this group are presented as medians with quartiles 1 and 3 for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables as appropriate in Table 1 . Additional measurements related to EECP treatment are in Table 2 . We used multiple imputation for the following 3 variables, which were missing at rates of approximately 18%: final heart rate, EECP-augmented systolic blood pressure, and EECP-augmented diastolic blood pressure.

| Variable | Median[Quartile 1, Quartile 3] Count (%) |

|---|---|

| Days from discharge to referral | 8 [1, 22] |

| Days from discharge to EECP ∗ | 31 [21, 41] |

| Age (years) | 68.2 [60.5, 73.9] |

| Men | 71 (72%) |

| Prior coronary bypass | 56 (57%) |

| Prior percutaneous coronary intervention | 54 (55%) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 37.5 [28.0, 47.5] |

| Existing Conditions | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 46 (47%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 14 (14%) |

| Thyroid disease | 12 (12%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 96 (97%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 79 (80%) |

| Hypertension | 85 (86%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 25 (25%) |

| Medications | |

| Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor | 83 (84%) |

| Beta-blocker | 90 (91%) |

| Diuretic | 92 (93%) |

| Median[Quartile 1, Quartile 3] | |

|---|---|

| EECP ∗ Pressure | 280 [240, 280] |

| Final Heart Rate | 71 [66, 80] |

| EECP Augmented Systolic Blood Pressure | 120 [111, 136] |

| EECP Augmented Diastolic Pressure | 68 [62, 77] |

| Augmentation Ratio | 1.0 [0.8, 1.2] |

| Completed Sessions † | 35 [35, 35] |

∗ EECP = Enhanced external counterpulsation.

† This had a mean of 32.4 sessions and standard deviation of 7.8 sessions.

We calculated the predicted probabilities of 90-day readmissions using the tool provided by Saito et al. If information needed for the prediction model was not recorded, we imputed data in a manner to yield the most conservative probability of readmission. For example, in the readmission model, patients with cognitive impairment had a positive coefficient and patients without had a coefficient of 0. Because cognitive impairment was not recorded in our data set, we assumed no patients had cognitive impairment. Even with this consideration, our cohort’s average predicted readmission rate was larger than that of the all-cause readmission rate in Medicare patients, so we used the Medicare national average as the hypothesized rate in an effort to be conservative. Thus, our hypothesized 90-day all-cause readmission rate was 34%. Given a cohort size of 99 and a 34% predicted readmission rate, we had 98% observed power to detect a 50% reduction in hospitalization with α of 0.05, in a 2-tailed test.

We performed a 1-sample test of proportion for the 90-day EECP cohort’s readmission rate compared to the predicted rate of readmission. We also evaluated readmission rates for the (baseline) high-risk populations of atrial fibrillation, the NYHA functional class 4, and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) angina grading scales of 3 or 4. All tests were performed using a significance level of 0.05.

Finally, we performed tests on available pre and post evaluations. We used a paired t test to examine the average difference in 6-minute walk distances and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to examine differences in before and after EECP Oxygen consumption and Duke Activity Status Index (DASI). Additionally, we used Fisher’s exact tests to examine changes in NYHA and CCS classes before and after EECP. All tests were performed using a significance level of 0.05.

Results

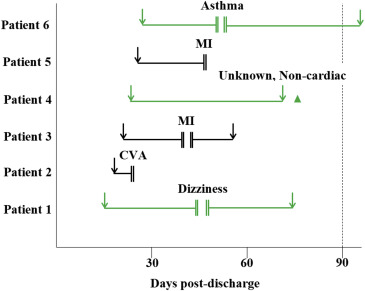

The observed and predicted readmission rates and the corresponding p values are in Figure 1 . There were only 6 unplanned readmissions within 90 days of discharge, occurring evenly between men and women. The rate of observed readmission was 6.1%, which was significantly lower than the average predicted rate of 34% (p value <0.0001); no deaths occurred. For the 6 patients who were readmitted, 1 was hospitalized after full treatment, 2 resumed and finished treatment, 1 continued treatment but was unable to complete 35 sessions, and the remaining 2 patients did not resume the program. The chronology of the 35 sessions, along with the 6 hospitalizations, are detailed in Figure 2 . Two patients were rehospitalized for myocardial infarction (MI), 1 for asthma, 1 for dizziness, 1 for stroke/cardiovascular accident, and 1 for an unknown noncardiac event. In the high-risk populations of atrial fibrillation, NYHA class IV symptoms, and class III/IV angina, readmission rates ranged from 5.6% to 12%, which were significantly lower than the predicted 34% (p values <0.05, Figure 3 ).