After reading this chapter you will be able to: The history of science and medicine is a fascinating topic, which begins in ancient times and progresses to the twenty-first century. Although respiratory care is a newer discipline, its roots go back to the dawn of civilization. The first written account of positive pressure ventilation using mouth-to-mouth resuscitation is thought to have been recorded more than 28 centuries ago.1 Air was thought to be one of the four basic elements by the ancients, and the practice of medicine dates back to ancient Babylonia and Egypt. The progression of science and medicine continued through the centuries, and development of the modern disciplines of anesthesiology, pulmonary medicine, and respiratory care during the twentieth century was dependent on the work of many earlier scientists and physicians. This chapter describes the history and development of the field of respiratory care and possible future directions for the profession. Respiratory care, also known as respiratory therapy, has been defined as the health care discipline that specializes in the promotion of optimal cardiopulmonary function and health.2 Respiratory therapists (RTs) apply scientific principles to prevent, identify, and treat acute or chronic dysfunction of the cardiopulmonary system.2 Respiratory care includes the assessment, treatment, management, control, diagnostic evaluation, education, and care of patients with deficiencies and abnormalities of the cardiopulmonary system.2 Respiratory care is increasingly involved in the prevention of respiratory disease, the management of patients with chronic respiratory disease, and the promotion of health and wellness.2 Respiratory therapists, also known as respiratory care practitioners, are health care professionals who are educated and trained to provide respiratory care to patients. About 75% of all respiratory therapists work in hospitals or other acute care settings.3 However, many respiratory therapists are employed in clinics, physicians’ offices, skilled nursing facilities, cardiopulmonary diagnostic laboratories, and public schools. Others work in research, disease management programs, home care, and industry. Some respiratory therapists work in colleges and universities, teaching students the skills they need to become respiratory therapists. Regardless of practice setting, all direct patient care services provided by respiratory therapists must be done under the direction of a qualified physician. Medical directors are usually physicians who are specialists in pulmonary or critical care medicine. A human resources survey conducted in 2009 revealed that there were approximately 145,000 respiratory therapists practicing in the United States3; this represented a 9.3% increase over a similar study conducted 4 years earlier in 2005. As the incidence of chronic respiratory diseases continues to increase, the demand for respiratory therapists is expected to be even greater in the years ahead. Although the respiratory therapist as a distinct health care provider was originally a uniquely North American phenomenon, since the 1990s there has been a steady increase in interest of other countries in having specially trained professionals provide respiratory care. This trend is referred to as the “globalization of respiratory care.” Several excellent reviews of the history of respiratory care have been written, and the reader is encouraged to review these publications.1,4–6 Summaries of notable historical events in science, medicine, and respiratory care are provided in Tables 1-1 and 1-2. A brief description of the history of science and medicine follows. TABLE 1-1 Data from references 1, 3–13, and 16. TABLE 1-2 Data from references 1, 3–13, and 16. Humans have been concerned about the common problems of sickness, disease, old age, and death since primitive times. Early cultures developed herbal treatments for many diseases, and surgery may have been performed in Neolithic times. Physicians practiced medicine in ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, and China.1,4,7 However, the foundation of modern Western medicine was laid in ancient Greece with the development of the Hippocratic Corpus.1,4,7,8 This ancient collection of medical treatises is attributed to the “father of medicine,” Hippocrates, a Greek physician who lived during the fifth and fourth centuries bc.1,7,8 Hippocratic medicine was based on four essential fluids, or “humors”—phlegm, blood, yellow bile, and black bile—and the four elements—earth (cold, dry), fire (hot, dry), water (cold, moist), and air (hot, moist). Diseases were thought to be humoral disorders caused by imbalances in these essential substances. Hippocrates believed there was an essential substance in air that was distributed to the body by the heart.1 The Hippocratic Oath, which admonishes physicians to follow certain ethical principles, is given in a modern form to many medical students at graduation.1,8 Aristotle (384-322 bc), a Greek philosopher and perhaps the first great biologist, believed that knowledge could be gained through careful observation.1,8 Aristotle made many scientific observations, including observations obtained by performing experiments on animals. Erasistratus (about 330-240 bc), regarded by some as the founder of the science of physiology, developed a pneumatic theory of respiration in Alexandria, Egypt, in which air (“pneuma”) entered the lungs and was transferred to the heart.1,7 Galen (130-199 ad) was an anatomist in Asia Minor whose comprehensive work dominated medical thinking for centuries.1,6,7 Galen also believed that inspired air contained a vital substance that somehow charged the blood through the heart.1 The Romans carried on the Greek traditions in philosophy, science, and medicine. With the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 ad, many Greek and Roman texts were lost and Europe entered a period during which there were few advances in science or medicine. In the seventh century ad, the Arabians conquered Persia, where they found and preserved many of the works of the ancient Greeks, including the works of Hippocrates, Aristotle, and Galen.1,7 A Golden Age of Arabian medicine (850-1050 ad) followed. An intellectual rebirth in Europe began in the twelfth century.1,7 Medieval universities were formed, and contact with the Arabs in Spain and Sicily reintroduced ancient Greek and Roman texts. Magnus (1192-1280) studied the works of Aristotle and made many observations related to astronomy, botany, chemistry, zoology, and physiology. The Renaissance (1450-1600) ushered in a period of scientific, artistic, and medical advances. da Vinci (1452-1519) studied human anatomy, determined that subatmospheric interpleural pressures inflated the lungs, and observed that fire consumed a vital substance in air without which animals could not live.1,4 Vesalius (1514-1564), considered to be the founder of the modern field of human anatomy, performed human dissections and experimented with resuscitation.1

History of Respiratory Care

Summarize some of the major events in the history of science and medicine.

Summarize some of the major events in the history of science and medicine.

Explain how the respiratory care profession got started.

Explain how the respiratory care profession got started.

Describe the historical development of the major clinical areas of respiratory care.

Describe the historical development of the major clinical areas of respiratory care.

Name some of the important historical figures in respiratory care.

Name some of the important historical figures in respiratory care.

Describe the major respiratory care educational, credentialing, and professional associations.

Describe the major respiratory care educational, credentialing, and professional associations.

Explain how the important respiratory care organizations got started.

Explain how the important respiratory care organizations got started.

Describe the development of respiratory care education.

Describe the development of respiratory care education.

Definitions

History of Respiratory Medicine and Science

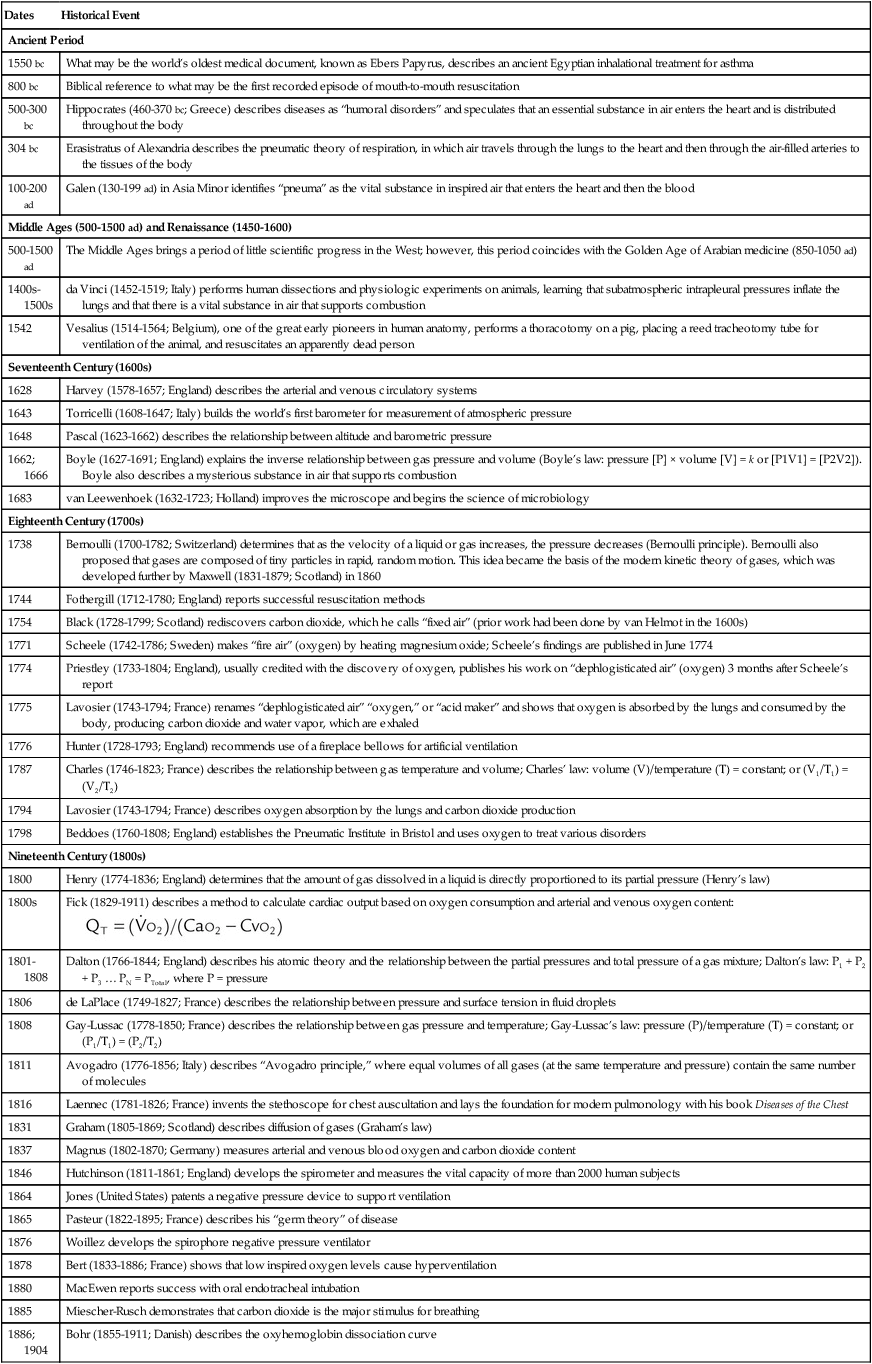

Dates

Historical Event

Ancient Period

1550 bc

What may be the world’s oldest medical document, known as Ebers Papyrus, describes an ancient Egyptian inhalational treatment for asthma

800 bc

Biblical reference to what may be the first recorded episode of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation

500-300 bc

Hippocrates (460-370 bc; Greece) describes diseases as “humoral disorders” and speculates that an essential substance in air enters the heart and is distributed throughout the body

304 bc

Erasistratus of Alexandria describes the pneumatic theory of respiration, in which air travels through the lungs to the heart and then through the air-filled arteries to the tissues of the body

100-200 ad

Galen (130-199 ad) in Asia Minor identifies “pneuma” as the vital substance in inspired air that enters the heart and then the blood

Middle Ages (500-1500 ad) and Renaissance (1450-1600)

500-1500 ad

The Middle Ages brings a period of little scientific progress in the West; however, this period coincides with the Golden Age of Arabian medicine (850-1050 ad)

1400s-1500s

da Vinci (1452-1519; Italy) performs human dissections and physiologic experiments on animals, learning that subatmospheric intrapleural pressures inflate the lungs and that there is a vital substance in air that supports combustion

1542

Vesalius (1514-1564; Belgium), one of the great early pioneers in human anatomy, performs a thoracotomy on a pig, placing a reed tracheotomy tube for ventilation of the animal, and resuscitates an apparently dead person

Seventeenth Century (1600s)

1628

Harvey (1578-1657; England) describes the arterial and venous circulatory systems

1643

Torricelli (1608-1647; Italy) builds the world’s first barometer for measurement of atmospheric pressure

1648

Pascal (1623-1662) describes the relationship between altitude and barometric pressure

1662; 1666

Boyle (1627-1691; England) explains the inverse relationship between gas pressure and volume (Boyle’s law: pressure [P] × volume [V] = k or [P1V1] = [P2V2]). Boyle also describes a mysterious substance in air that supports combustion

1683

van Leewenhoek (1632-1723; Holland) improves the microscope and begins the science of microbiology

Eighteenth Century (1700s)

1738

Bernoulli (1700-1782; Switzerland) determines that as the velocity of a liquid or gas increases, the pressure decreases (Bernoulli principle). Bernoulli also proposed that gases are composed of tiny particles in rapid, random motion. This idea became the basis of the modern kinetic theory of gases, which was developed further by Maxwell (1831-1879; Scotland) in 1860

1744

Fothergill (1712-1780; England) reports successful resuscitation methods

1754

Black (1728-1799; Scotland) rediscovers carbon dioxide, which he calls “fixed air” (prior work had been done by van Helmot in the 1600s)

1771

Scheele (1742-1786; Sweden) makes “fire air” (oxygen) by heating magnesium oxide; Scheele’s findings are published in June 1774

1774

Priestley (1733-1804; England), usually credited with the discovery of oxygen, publishes his work on “dephlogisticated air” (oxygen) 3 months after Scheele’s report

1775

Lavosier (1743-1794; France) renames “dephlogisticated air” “oxygen,” or “acid maker” and shows that oxygen is absorbed by the lungs and consumed by the body, producing carbon dioxide and water vapor, which are exhaled

1776

Hunter (1728-1793; England) recommends use of a fireplace bellows for artificial ventilation

1787

Charles (1746-1823; France) describes the relationship between gas temperature and volume; Charles’ law: volume (V)/temperature (T) = constant; or (V1/T1) = (V2/T2)

1794

Lavosier (1743-1794; France) describes oxygen absorption by the lungs and carbon dioxide production

1798

Beddoes (1760-1808; England) establishes the Pneumatic Institute in Bristol and uses oxygen to treat various disorders

Nineteenth Century (1800s)

1800

Henry (1774-1836; England) determines that the amount of gas dissolved in a liquid is directly proportioned to its partial pressure (Henry’s law)

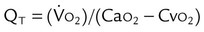

1800s

Fick (1829-1911) describes a method to calculate cardiac output based on oxygen consumption and arterial and venous oxygen content:

1801-1808

Dalton (1766-1844; England) describes his atomic theory and the relationship between the partial pressures and total pressure of a gas mixture; Dalton’s law: P1 + P2 + P3 … PN = PTotal, where P = pressure

1806

de LaPlace (1749-1827; France) describes the relationship between pressure and surface tension in fluid droplets

1808

Gay-Lussac (1778-1850; France) describes the relationship between gas pressure and temperature; Gay-Lussac’s law: pressure (P)/temperature (T) = constant; or (P1/T1) = (P2/T2)

1811

Avogadro (1776-1856; Italy) describes “Avogadro principle,” where equal volumes of all gases (at the same temperature and pressure) contain the same number of molecules

1816

Laennec (1781-1826; France) invents the stethoscope for chest auscultation and lays the foundation for modern pulmonology with his book Diseases of the Chest

1831

Graham (1805-1869; Scotland) describes diffusion of gases (Graham’s law)

1837

Magnus (1802-1870; Germany) measures arterial and venous blood oxygen and carbon dioxide content

1846

Hutchinson (1811-1861; England) develops the spirometer and measures the vital capacity of more than 2000 human subjects

1864

Jones (United States) patents a negative pressure device to support ventilation

1865

Pasteur (1822-1895; France) describes his “germ theory” of disease

1876

Woillez develops the spirophore negative pressure ventilator

1878

Bert (1833-1886; France) shows that low inspired oxygen levels cause hyperventilation

1880

MacEwen reports success with oral endotracheal intubation

1885

Miescher-Rusch demonstrates that carbon dioxide is the major stimulus for breathing

1886; 1904

Bohr (1855-1911; Danish) describes the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve

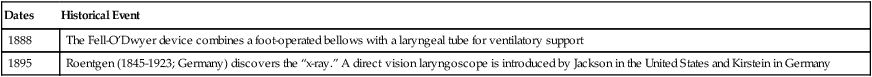

1888

The Fell-O’Dwyer device combines a foot-operated bellows with a laryngeal tube for ventilatory support

1895

Roentgen (1845-1923; Germany) discovers the “x-ray.” A direct vision laryngoscope is introduced by Jackson in the United States and Kirstein in Germany

Twentieth Century

Early 1900s

Bohr (1855-1911; Denmark), Hasselbach (1874-1962; Denmark), Krogh (1874-1940; Denmark), Haldane (1860-1936; Scotland), Barcroft (1872-1947; Ireland), Priestly (1880-1941; Britain), Y. Henderson (1873-1944; United States), L.J. Henderson (1878-1942; United States), Fenn (1893-1971; United States), Rahn (1912-1990; United States), and others make great strides in respiratory physiology and the understanding of oxygenation, ventilation, and acid-base balance

1904

Bohr, Hasselbach, and Krogh (1874-1940) describe the relationships between oxygen and carbon dioxide transport. Sauerbruch (1875-1951; Germany) uses a negative pressure operating chamber for surgery in Europe

1907

von Linde (1842-1934; Germany) begins large-scale commercial preparation of oxygen

1909

Melltzer (1851-1920; United States) introduces oral endotracheal intubation

1910

Oxygen tents are in use, and the clinical use of aerosolized epinephrine is introduced

1911

Drager (1847-1917; Germany) develops the Pulmotor ventilator for use in resuscitation

1913

Jackson develops a laryngoscope to insert endotracheal tubes

1918

Oxygen mask is used to treat combat-induced pulmonary edema

1919

Strohl (1887-1977; France) suggests the use of FVC as a measure of pulmonary function

1920

Hill develops an oxygen tent to treat leg ulcers

1926

Barach develops an oxygen tent with cooling and carbon dioxide removal

1928

Drinker develops his “iron lung” negative pressure ventilator

1938

Barach develops the meter mask for administering dilute oxygen. Boothby, Lovelace, and Bulbulian devise the BLB mask at the Mayo Clinic for delivering high concentrations of oxygen

1940

Isoproterenol, a potent beta-1 and beta-2 bronchodilator administered via aerosol, is introduced. Most common side effects are cardiac (beta-1)

1945

Motley, Cournand, and Werko use IPPB to treat various respiratory disorders

1947

The ITA is formed in Chicago, Illinois. The ITA later becomes the AARC

1948

Bennett introduces the TV-2P positive pressure ventilator

1948

FEV1 is introduced as a pulmonary function measure of obstructive lung disease

1951

Isoetherine (Bronkosol), a preferential beta-2 aerosol bronchodilator with fewer cardiac side effects, is introduced

1952

Mørch introduces the piston ventilator

1954

The ITA becomes the AAIT

1958

Bird introduces the Bird Mark 7 positive pressure ventilator

1960

The Campbell Ventimask for delivering dilute concentrations of oxygen is introduced

1961

Jenn becomes the first registered respiratory therapist. Also, metaproterenol, a preferential beta-2 bronchodilator, is introduced

1963

Board of Schools is formed to accredit inhalation therapy educational programs

1964

The Emerson Postoperative Ventilator (3-PV) positive pressure volume ventilator is introduced

1967

The Bennett MA-1 volume ventilator is introduced, ushering in the modern age of mechanical ventilatory support for routine use in critical care units

1967

Combined pH-Clark-Severinghaus electrode is developed for rapid blood gas analysis

1968

Fiberoptic bronchoscope becomes available for clinical use. The Engström 300 and Ohio 560 positive pressure volume ventilators are introduced

1969

ARDS and PEEP are described by Petty, Ashblaugh, and Bigelow

1970

Swan-Ganz catheter developed for measurement of pulmonary artery pressures. The ARCF is incorporated. The JRCITE is incorporated to accredit respiratory therapy educational programs

1971

Continuous positive airway pressure is introduced by Gregory. Respiratory Care journal is named

1972

Siemens Servo 900 ventilator is introduced

1973

IMV is described by Kirby and Downs. The AAIT becomes the AART

1974

IMV Emerson ventilator is introduced

1974

NBRT is formed

1975

Bourns Bear I ventilator is introduced

1977

The JRCITE becomes the JRCRTE

1978

Puritan Bennett introduces the MA-2 volume ventilator. The AAR Times magazine is introduced

1979

AIDS is recognized by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC [later, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention])

1982

Siemens Servo 900C and Bourns Bear II ventilators are introduced

1983

The NBRT becomes the NBRC

1983

President Reagan signs proclamation declaring National Respiratory Care Week

1984

Bennett 7200 microprocessor controlled ventilator is introduced

1984

The AART is renamed the AARC

1991

Servo 300 ventilator is introduced

1992, 1993

The AARC holds national respiratory care education consensus conferences

1994

The CDC publishes the first guidelines for the prevention of VAP

1998

The CoARC is formed, replacing the JRCRTE

Twenty-First Century

2002

The NBRC adopts a continuing competency program for respiratory therapists to maintain their credentials

2002

The Tripartite Statements of Support are adopted by the AARC, NBRC, and CoARC to advance respiratory care education and credentialing

2003

The AARC publishes its white paper on the development of baccalaureate and graduate education in respiratory care. Asian bird flu appears in South Korea

2004

The Fiftieth AARC International Congress is held in New Orleans

2005

Number of working respiratory therapists in the United States reaches 132,651

2006

The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services begins national awareness and education campaign for COPD. The AARC works with government officials to recruit and train respiratory therapists for disaster response

2007

The first AARC president to serve a 2-year term begins term of office

2008

First of three conferences held for 2015 and Beyond strategic initiative of the AARC

Ancient Times

Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the Enlightenment Period

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

History of Respiratory Care