Ethanol and The Heart

Michael H. Criqui

Lori B. Daniels

Overview

Epidemiologic studies have consistently shown that light to moderate alcohol consumption is associated with reduced morbidity and mortality from coronary heart disease (CHD) (1). However, higher levels of alcohol use can be cardiotoxic and contribute to hypertension, arrhythmias, and cardiomyopathy and ultimately lead to increased cardiovascular disease (CVD). In addition, other disease endpoints, including cancer, cirrhosis, and accidental and violent death, are increased at higher levels of alcohol consumption. This J-shaped relationship between alcohol intake and survival has been extensively described (2).

Epidemiology

Approximately 63% of the U.S. population consumes alcohol, and approximately one tenth of these are considered heavy drinkers. The prevalence of alcohol consumption differs by gender and by age, and is higher in men and in younger individuals (3). Among the identifiable etiologies of nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) in the United States, alcohol is the most common in both sexes and all races, accounting for almost half of all cases (4). Furthermore, excessive alcohol intake is reported in 3% to 40% of patients with otherwise unexplained idiopathic DCM (5). With early detection and abstinence from further alcohol, cardiac function can recover in some cases (6,7).

Anatomy and Pathology

Specimens from autopsies and biopsies of alcoholic hearts have shown varying degrees of morphologic abnormalities, depending on the stage and progression of the disease. During the preclinical phase, left ventricular (LV) dilation and a normal or moderately increased LV mass may be seen. Some patients may also have wall thickening, which may offset the LV dilation and lead to a compensated, asymptomatic state. With progression of the disease, varying degrees of cardiomegaly reflecting chamber dilation are seen, particularly when there is concomitant mitral insufficiency. On gross observation, the heart appears flabby, large, and pale (4).

The exact pathogenesis of alcoholic cardiomyopathy is incompletely understood. At a microscopic level, alcohol affects mitochondrial structure and function, which can be observed on biopsy (8). Changes in the sarcoplasmic reticulum, contractile proteins, and calcium homeostasis also contribute to myocardial cell dysfunction (4).

Pathophysiology

Acutely, ethanol ingestion exerts a transient direct toxic effect on cardiac performance, acting as a negative inotrope (9,10,11). Increased autonomic activity may lead to a modest increase in heart rate (10). Because these actions of alcohol tend to have opposing effects, overt evidence of hemodynamic derangements from alcohol can be minimal in healthy individuals. Still, asymptomatic cardiac dysfunction may be present even in healthy “social drinkers” who consume smaller quantities of alcohol (12).

The transient negative inotropic effect on myocardial function can become permanent with chronic consumption. In addition, chronic users often exhibit greater hemodynamic derangements from alcohol, especially in the setting of underlying cardiac disease. Increased diastolic stiffness, possibly due to accumulation of myocardial collagen in the extracellular matrix, may contribute to clinical presentations of the alcoholic heart. The role of ethanol in the accumulation of collagen can be enhanced by the use of tobacco (13), which is a common coaddiction. With both acute and chronic ingestion, abnormalities in myofibrillar protein turnover can contribute to myocardial damage, perhaps with involvement of oxidative stress (14). Reactive oxygen species may impair myocyte function by interfering with calcium handling (4). Toxic effects of acetaldehyde and fatty acid ethyl esters, metabolites and byproducts of alcohol, may also potentiate myocardial damage via impairment of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (9).

Alcohol-induced hypertension also contributes to chronic myocardial dysfunction in chronic drinkers, in a dose-related fashion (15,16,17,18). Individuals who drink more than two

alcoholic beverages per day have twice the incidence of hypertension compared with nondrinkers (19).

alcoholic beverages per day have twice the incidence of hypertension compared with nondrinkers (19).

Thiamine deficiency is another factor contributing to alcoholic cardiomyopathy in many instances. Approximately 15% of asymptomatic alcoholics are moderately deficient in thiamine (20). The physiologic derangements seen in beriberi heart disease, however, are different from those seen in alcoholic cardiomyopathy, and include a hyperdynamic state with decreased peripheral vascular resistance, increased cardiac output, tachycardia, and biventricular failure (21).

Finally, some alcoholic beverages contain additives such as cobalt that may be directly cardiotoxic (22).

Clinical Presentations

Hypertension

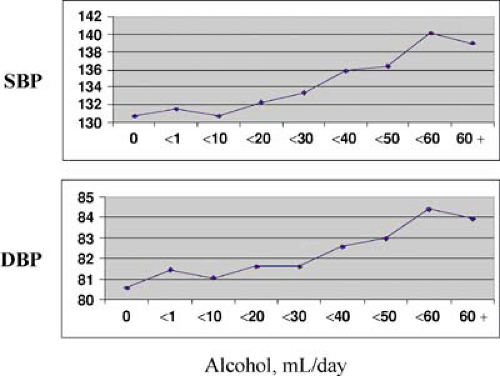

Heavy alcohol consumption is an independent risk factor for hypertension, with up to a twofold increased incidence of hypertension in drinkers compared with nondrinkers (15,17,19,23,24). Some studies have shown an association with increased incidence of hypertension from even low to moderate alcohol consumption (17,24), although the risk appears to be dose dependent (15,16,17). At three or more drinks per day, there is a relatively linear relationship between alcohol intake and blood pressure in a variety of populations, irrespective of race and gender (25) (Fig. 10.1).

Cardiomyopathy and Heart Failure

Chronic ethanol abuse induces a marked decrease in left ventricular function compared to normal individuals. In fact, alcohol has been implicated as a major cause of up to 30% of all dilated cardiomyopathies (26). The risk of developing alcoholic cardiomyopathy is related to both the mean daily alcohol intake and the duration of drinking, although there is significant individual susceptibility to the toxic effects of alcohol (26,27,28). Most patients in whom alcoholic cardiomyopathy develops have been drinking greater than 80 grams per day for more than 5 years (27,29). Early changes in LV function in chronic asymptomatic alcoholics demonstrate dilation with preserved ejection fraction and impaired relaxation. With increased duration of alcoholism, the LV diastolic filling abnormalities progress (30) and there is progressive decline in LV systolic function (26).

As previously mentioned, thiamine deficiency should also be considered as a potential factor contributing to alcoholic cardiomyopathy because 15% of asymptomatic alcoholics are moderately deficient in thiamine as determined by dietary history and excretion of vitamin metabolites (20). For the diagnosis of beriberi heart disease, several criteria are required, including a history of thiamine deficiency for more than 3 months, absence of another etiology of heart failure, evidence of peripheral neuropathy, and a therapeutic response to thiamine (21).

Dysrhythmias

Dysrhythmias are associated with underlying changes in myocardial composition and electrophysiology as a consequence of chronic alcohol ingestion, although they may occur in up to 60% of binge drinkers even in the absence of underlying myocardial damage (31,32). Electrolyte abnormalities such as hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia, which occur more frequently in chronic alcoholics, may also contribute (33,34,35).

The most common alcohol-related arrhythmias are paroxysmal atrial arrhythmias, especially atrial fibrillation, although ventricular dysrhythmias can also occur (31,36). Holiday heart describes the development of an acute arrhythmic process, generally atrial fibrillation, after an episode of heavy alcohol consumption. These episodes frequently occur over long weekends or holidays, thus the name holiday heart (31).

Sudden Cardiac Death

An increased incidence of sudden cardiac death (SCD) has been found among the alcoholic population (37,38), with one study showing heavy drinkers with a 60% increased risk compared with occasional or light drinkers (39).

Dose is an important factor in determining the relationship of alcohol to the development of sudden death. In contrast to the increased risk of sudden death with heavy drinking, moderate or light alcohol intake (two to six drinks per week) reduced sudden death in a prospective study of more than 21,000 male physicians compared with those who rarely or never consumed alcohol (40). This dose-dependent relationship was also seen in an analysis of the Framingham population, in which individuals who consumed more than 2,500 grams of alcohol per month had an increased risk of sudden death (41).

Possible mechanisms for the observed association between alcohol and SCD include prolongation of the QT interval leading to ventricular tachyarrhythmias, rapid degeneration of ventricular tachycardias into ventricular fibrillation, electrolyte abnormalities, sympathoadrenal stimulation, and decreased vagal input (25).

Diagnosis, Management, and Prognosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree